PROFESSORS: CHERYL ATKINSON AND WILL GALLOWAY

20/20 Tokyo Toronto

20/20 Tokyo Toronto

By now it is common knowledge that most of humanity lives in cities. The

shift towards urbanism is relatively recent however. It was only in 2007 for

instance that the world’s urban population officially passed the 50% mark. It

is not surprising then that cities all over the world are collections of

planned and un-planned communities, infrastructure, and buildings. Nor should

we be surprised that there is so much dysfunction in even the most popular

urban areas. This is as true of megacities like Tokyo, with a population of 37

million people, as it is of “smaller” cities like Toronto, with seven- million

people. What is also evident is that the global migration to cities of the last

twenty-five years is going to continue for the next twenty-five years with the

GTA estimated to add another 45% to its population exacerbating the housing

affordability and transportation crisis we already experience.

As architects we are asked to respond to an ever-lengthening list of fundamental problems, including climate change, natural disasters, shifting demographics, economics, new construction technology, resilience, social equity, and the sharing economy. If past is prologue, the list will continue to grow and much of what we will deal with will not be predictable or within the capacity of architecture to change. However, when, where and how does architecture and the profession have capacity to accommodate and improve lives? The history of housing throughout the modern period includes a plethora of successful buildings and ideas as well as a variety of documented failures from which we can learn.

In this studio we will address the agency of the architect with respect to the global urban housing crisis. Only by understanding the variety of externalities that have determined built form can we begin to propose and test alternatives forms, typologies, processes, politics and strategies and that can help make housing not only more accessible, but more responsive to the humanity of society. Housing is indelibly linked to our sense of self, family and community. Like all architecture of merit, it should seek to satisfy our emotional and intellectual needs as well as our physical accommodations.

This studio takes advantage of two cities as sites, namely Toronto and Tokyo. It asks students to develop an architectural solution to the missing middle, the buildings that need to be built to accommodate a radically growing population in Toronto, and a radically depopulating Tokyo.

As architects we are asked to respond to an ever-lengthening list of fundamental problems, including climate change, natural disasters, shifting demographics, economics, new construction technology, resilience, social equity, and the sharing economy. If past is prologue, the list will continue to grow and much of what we will deal with will not be predictable or within the capacity of architecture to change. However, when, where and how does architecture and the profession have capacity to accommodate and improve lives? The history of housing throughout the modern period includes a plethora of successful buildings and ideas as well as a variety of documented failures from which we can learn.

In this studio we will address the agency of the architect with respect to the global urban housing crisis. Only by understanding the variety of externalities that have determined built form can we begin to propose and test alternatives forms, typologies, processes, politics and strategies and that can help make housing not only more accessible, but more responsive to the humanity of society. Housing is indelibly linked to our sense of self, family and community. Like all architecture of merit, it should seek to satisfy our emotional and intellectual needs as well as our physical accommodations.

This studio takes advantage of two cities as sites, namely Toronto and Tokyo. It asks students to develop an architectural solution to the missing middle, the buildings that need to be built to accommodate a radically growing population in Toronto, and a radically depopulating Tokyo.

Tokyo Toronto Comparison Research

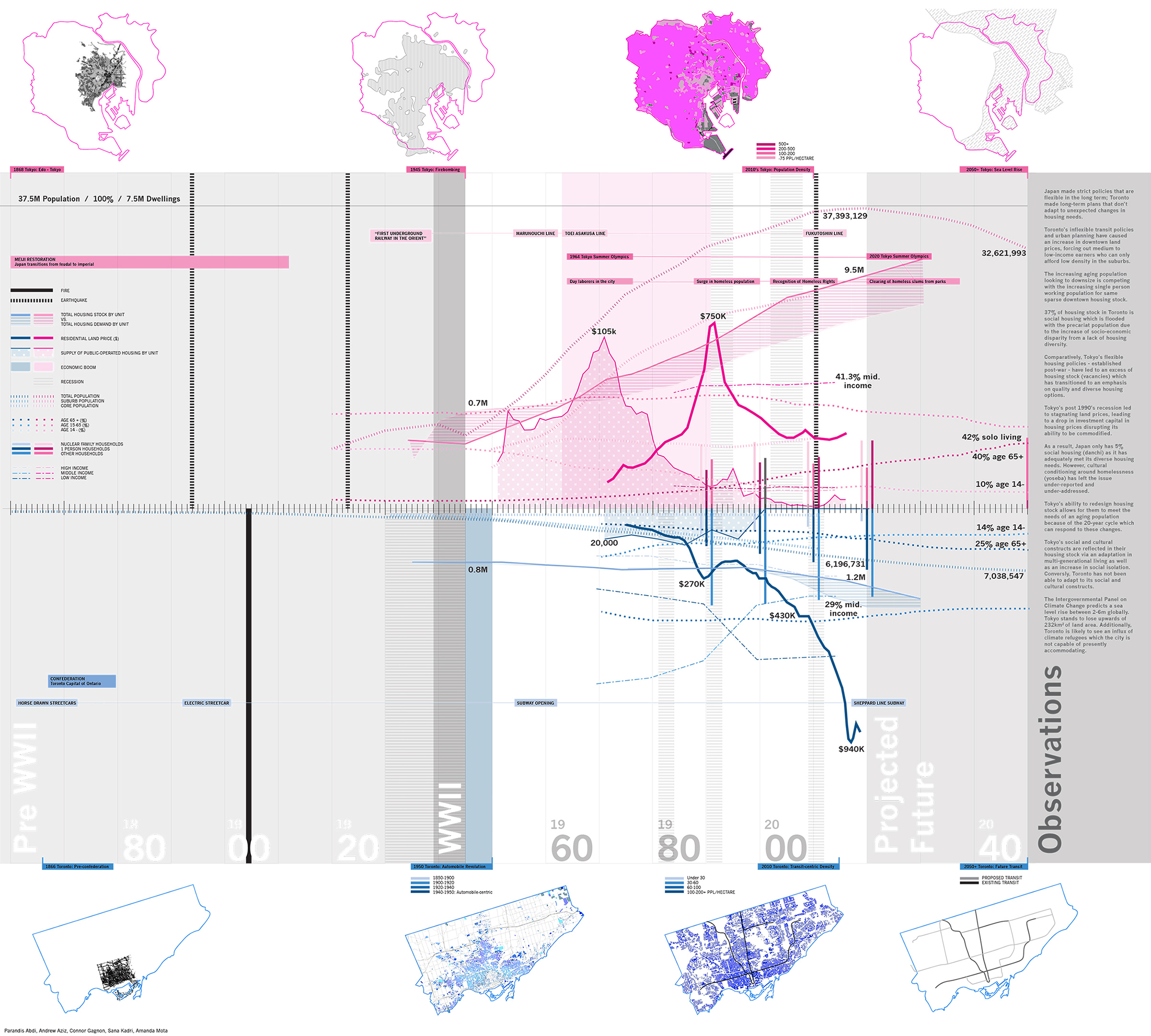

This comparative timeline looks at Tokyo’s and Toronto’s historic events, demographics, politics and projected future data as they relate to housing issues.

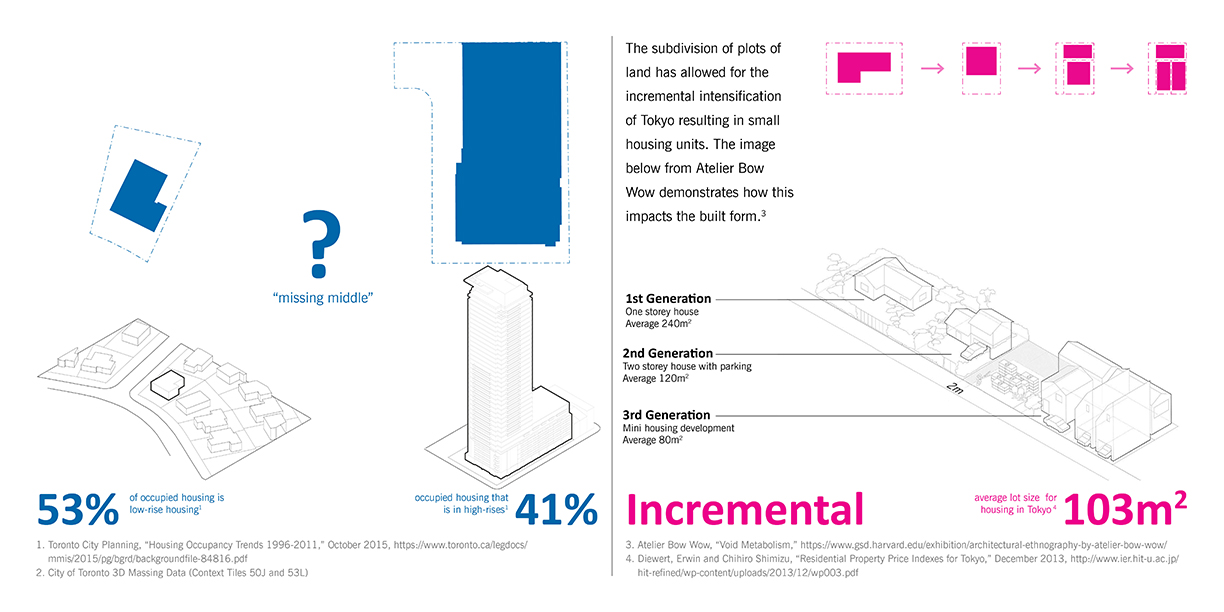

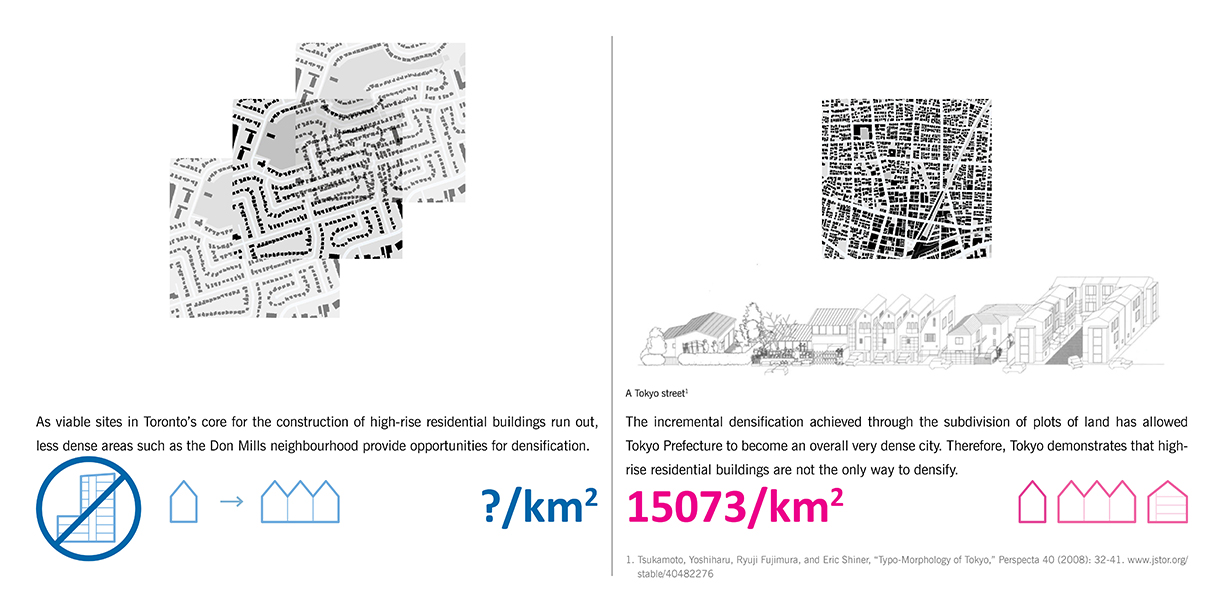

The purpose of this section, as a small section of a 3-week targeted research report prepared by the entire class, was to study and compare the building typologies, scales, and population densities of a few typical neighbourhoods in Toronto and Tokyo. The findings of the research informed the housing strategies used later in the course.