Surveillance and Control:

The Role of Architecture in a Digital Monitoring World

Introduction

As our lives start to shift into a majority online presence, we are forced to take a step back and re-evaluate the drastic change the digital world has on our lives, and our society. The technical realm has been slowly and steadily overtaking and redefining every rule and order of our live. We continue to celebrate the capabilities the technical realm offers without questioning the risks and fragility it leaves behind.1

I’ve often noticed the strange way people with laptops tend to put a little sticker over their built-in camera. They do so as if their camera was an eye-like hole that represents the vast of surveillance beyond. This paranoia is fueled by countless news and media outlets that propagate the idea of a faceless FBI detachment supposedly watching your every move2, where homes and bedrooms might be considered private to strangers, but exposed to anyone who has the ability to access cameras and phones. It begs the question – is there still privacy in an ever-changing digital world?

Essay Structure

This essay will explore how surveillance and control have evolved throughout the years, and how its shift to the digital realm creates new possibilities for architectural responses. New technological advances, such as artificial intelligence and facial recognition, could prove to be the foundation for new architectural typologies and design rules, rendering an unrecognizable future. The essay will start with traditional forms of surveillance, such as sovereign societies the design of panopticons, later diving into modern theories of control regimes such as the concept of liquid surveillance and pharmacopornographic societies. Finally, it will explore the case study of Sidewalk Labs and other potential new developments of similar smart cities, in regards to how elements of surveillance played a part in their demise.

As our lives start to shift into a majority online presence, we are forced to take a step back and re-evaluate the drastic change the digital world has on our lives, and our society. The technical realm has been slowly and steadily overtaking and redefining every rule and order of our live. We continue to celebrate the capabilities the technical realm offers without questioning the risks and fragility it leaves behind.1

I’ve often noticed the strange way people with laptops tend to put a little sticker over their built-in camera. They do so as if their camera was an eye-like hole that represents the vast of surveillance beyond. This paranoia is fueled by countless news and media outlets that propagate the idea of a faceless FBI detachment supposedly watching your every move2, where homes and bedrooms might be considered private to strangers, but exposed to anyone who has the ability to access cameras and phones. It begs the question – is there still privacy in an ever-changing digital world?

Essay Structure

This essay will explore how surveillance and control have evolved throughout the years, and how its shift to the digital realm creates new possibilities for architectural responses. New technological advances, such as artificial intelligence and facial recognition, could prove to be the foundation for new architectural typologies and design rules, rendering an unrecognizable future. The essay will start with traditional forms of surveillance, such as sovereign societies the design of panopticons, later diving into modern theories of control regimes such as the concept of liquid surveillance and pharmacopornographic societies. Finally, it will explore the case study of Sidewalk Labs and other potential new developments of similar smart cities, in regards to how elements of surveillance played a part in their demise.

The Death of Dark Alleys & Removal of Architecture as Vessel

As digital surveillance becomes more ubiquitous, it will cause the removal of so-called dark alleys in the built environment. No longer will there be spaces that are invisible to the omnipresence of surveillance, which may lead to the facilitation of spatial complexity due to the sense that every nook and cranny has the potential to be monitored at all times. Fundamentally, on an architectural scale, it would cease to influence the design of architecture, due to the simple fact that architecture itself is saturated by surveillance. Architecture transitions from a vessel of power and control, gradually to nothing more than fundamental shelter itself. Surveillance is a tool for social control, but it should not be thought of as a tool for stopping crime. Instead, surveillance should be considered an aid to post-crime punishment. Unlike Minority Report, there is no guarantee that an artificially intelligent machine can predict crime on an unbiased scale. Thus, surveillance, regardless of digital or physical manifestation, should be about maintaining social justice, and at the foundation of it, the use of mass surveillance is a political issue of use and policy.

Traditional forms of Surveillance

The Sovereign Society - Torture

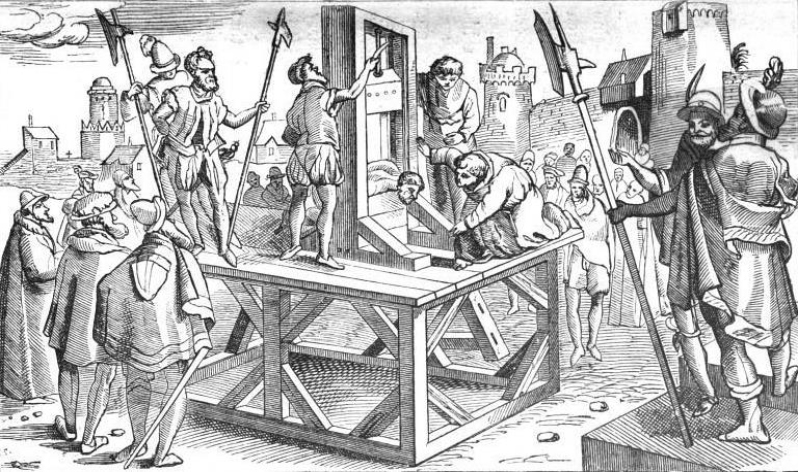

To understand the history of social control, Foucault begins with the most basic understanding of control – that of monarchies and sovereign power.3 Generally referring to classical or medieval times, these forms of government have minimal observational and surveillance power, unable to physically see into the homes of every citizen. Instead, they must resort to basic public execution and corporal punishments to make a spectacle of their control over society. Public hangings, display of bodies, these were all a form of ceremony to send a message to the public, a warning to those who would dare rebel and attack the authority of those in power. Thus, any crime automatically becomes an opportunity to reinforce the rigid hierarchical structure of a sovereign society. As seen in figure 1, as Foucault describes, “These convicts, distinguished by their ‘infamous dress’ and shaven heads, ‘were brought before the public. The sport of the idle and the vicious, they often become incensed, and naturally took violent revenge upon the aggressors.

As digital surveillance becomes more ubiquitous, it will cause the removal of so-called dark alleys in the built environment. No longer will there be spaces that are invisible to the omnipresence of surveillance, which may lead to the facilitation of spatial complexity due to the sense that every nook and cranny has the potential to be monitored at all times. Fundamentally, on an architectural scale, it would cease to influence the design of architecture, due to the simple fact that architecture itself is saturated by surveillance. Architecture transitions from a vessel of power and control, gradually to nothing more than fundamental shelter itself. Surveillance is a tool for social control, but it should not be thought of as a tool for stopping crime. Instead, surveillance should be considered an aid to post-crime punishment. Unlike Minority Report, there is no guarantee that an artificially intelligent machine can predict crime on an unbiased scale. Thus, surveillance, regardless of digital or physical manifestation, should be about maintaining social justice, and at the foundation of it, the use of mass surveillance is a political issue of use and policy.

Traditional forms of Surveillance

The Sovereign Society - Torture

To understand the history of social control, Foucault begins with the most basic understanding of control – that of monarchies and sovereign power.3 Generally referring to classical or medieval times, these forms of government have minimal observational and surveillance power, unable to physically see into the homes of every citizen. Instead, they must resort to basic public execution and corporal punishments to make a spectacle of their control over society. Public hangings, display of bodies, these were all a form of ceremony to send a message to the public, a warning to those who would dare rebel and attack the authority of those in power. Thus, any crime automatically becomes an opportunity to reinforce the rigid hierarchical structure of a sovereign society. As seen in figure 1, as Foucault describes, “These convicts, distinguished by their ‘infamous dress’ and shaven heads, ‘were brought before the public. The sport of the idle and the vicious, they often become incensed, and naturally took violent revenge upon the aggressors.

To prevent them from returning injuries which might be inflicted on them, they were encumbered with iron collars and chains to which bombshells were attached, to be dragged along while they performed their degrading service, under the eyes of keepers armed with swords, blunderbusses and other weapons of destruction.”4 In these societies, particularly the ones from before the 18th century, communication was mainly through word-of-mouth, so you could not have any type of information that is guaranteed to reach every household or individual.5 If you want to instill fear into the hearts of many, the best way to do so is through something so public and monumental that hundreds would watch, but thousands would hear through tales and rumors. Few events have as much impact on the masses than a public corporal punishment. If the impression of the gallows at a public square was enough of a reminder of sovereign power, then the society was more or less controlled, the social order was maintained, and the existing power structure was preserved. The architecture that represented power, in this case, was a simple artifact that reinforced the possibility of such public corporal punishment, working alongside a similar representation of the power and stability of higher power, such as castle walls, rigid but lavish palaces, etc. These types of architecture help to promote the one concept that is vital to society – the absoluteness of power.6

A Panopticon Society of Control - Punishment

The 18th century marked a radical shift in the concept of surveillance and social control, with the introduction of the panopticon.7 The idea began as a basic solution to solve issues of watching factory workers in a particularly underperforming factory. However, this architectural format was quickly adapted as a more effective way to organize a prison layout. This began the shift in power and control in a post-sovereign world. The panopticon was likely perceived to be, at first, a utilitarian organizational method that would effectively utilize minimal manpower to maximize efficiency. In the case of prisons, it meant having minimal guards to watch over a maximum number of prisoners. However, it was the dynamic power balance, this asymmetry between watcher and prisoner, that became central to later concepts of surveillance and control. The watchers are, in this instance, the ones who have the power. Armed with the knowledge of knowing who and what they are observing at any given time. The inmates, on the other hand, are severely disadvantaged because they have lost the ability to know if they are being watched or not. A constant prickling fear of punishment due to the unknown presence of the all-seeing eye leads to self-policing.8

![Figure 2. The Panopticon]()

The panopticon thus effectively implemented social control by the few (powerful) over the many (society). As compared to the sovereign society, the fear of physical punishment remains, but the representation of power through knowledge is transitioned to a non-visual state. Instead of fearing guards or police physically checking in at random times, now the mental idea of authority hovers over the inmate’s heads constantly. Foucault later explains this very concept in Discipline and Punish, “the Panopticon must not be understood as a dream building: it is the diagram of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form; its functioning, abstracted from any obstacle, resistance or friction, must be represented as a pure architectural and optical system: it is in fact a figure of political technology that may and must be detached from any specific use.”9 That is to say, the actual architecture of the panopticon means very little. It is stead the shift of power within the design that lays the foundation for a new surveillance society. Bauman similarly dissects the concept, citing it as being an opposition between freedom and unfreedom. A peaceful existence is all that is required of the inmates, and as it is humanity’s basic instinct, they will seek happiness through their own behavioral control.10 The small nudge of reminder through a guard tower placed at the center of their lives, physical or digital, is enough to assure them that peace will be maintained so long as they live under the design of the powerful.11

The 18th century marked a radical shift in the concept of surveillance and social control, with the introduction of the panopticon.7 The idea began as a basic solution to solve issues of watching factory workers in a particularly underperforming factory. However, this architectural format was quickly adapted as a more effective way to organize a prison layout. This began the shift in power and control in a post-sovereign world. The panopticon was likely perceived to be, at first, a utilitarian organizational method that would effectively utilize minimal manpower to maximize efficiency. In the case of prisons, it meant having minimal guards to watch over a maximum number of prisoners. However, it was the dynamic power balance, this asymmetry between watcher and prisoner, that became central to later concepts of surveillance and control. The watchers are, in this instance, the ones who have the power. Armed with the knowledge of knowing who and what they are observing at any given time. The inmates, on the other hand, are severely disadvantaged because they have lost the ability to know if they are being watched or not. A constant prickling fear of punishment due to the unknown presence of the all-seeing eye leads to self-policing.8

The panopticon thus effectively implemented social control by the few (powerful) over the many (society). As compared to the sovereign society, the fear of physical punishment remains, but the representation of power through knowledge is transitioned to a non-visual state. Instead of fearing guards or police physically checking in at random times, now the mental idea of authority hovers over the inmate’s heads constantly. Foucault later explains this very concept in Discipline and Punish, “the Panopticon must not be understood as a dream building: it is the diagram of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal form; its functioning, abstracted from any obstacle, resistance or friction, must be represented as a pure architectural and optical system: it is in fact a figure of political technology that may and must be detached from any specific use.”9 That is to say, the actual architecture of the panopticon means very little. It is stead the shift of power within the design that lays the foundation for a new surveillance society. Bauman similarly dissects the concept, citing it as being an opposition between freedom and unfreedom. A peaceful existence is all that is required of the inmates, and as it is humanity’s basic instinct, they will seek happiness through their own behavioral control.10 The small nudge of reminder through a guard tower placed at the center of their lives, physical or digital, is enough to assure them that peace will be maintained so long as they live under the design of the powerful.11

Post-Panopticon Regime – Discipline

Slowly but surely, prisons began to change, alongside society and its use of control. What was formerly no more than a tiny space in which solitude, a lack of freedom and engineered boredom was the main focus of prisons, there now exists a new set of rules that began to shift how people were to behave. The exact scale of control changed drastically, from the former treatment of prisoners as a whole to the gradual separation of the mind from the body. New regimes and rules in prison are now designed to attack the mind, creating what Foucault called a more “docile” person.12 A subtleness went into the design of these rules and regimes, it was less about force and more about getting the body and mind to become adapt to certain binding rules, to adapt to a series of influences that would eventually become manifested within. If a man were to be woken up at 6 am every single day for 10 years, he would continue waking up at this time for the rest of his life. His mind and body have become accustomed to this way of living, and thus he is a slave of this simple rule.13 Current society tends to think of past decades as less reformed, more barbaric, and this mindset is applied to the previous way punishment regimes were run. Activities such as flagging and simple confinement are understood to be savage behaviors, as individuals of power believed that reform should come from the mind, not the body. More “enlightened” thinkers sought to develop ways to create a more docile and safe society, and thus the discipline regime was pushed to be incorporated into other facilities. The most notable ones are schools and militaries. This concept is not hard to see in the current context, as both schools and militaries drill into individuals the importance of rules and discipline. Young children are expected to bury their instincts to explore and instead must sit quietly and obey all the rules of their teacher. Similarly, militaries are even more strict when it comes to rigid timetables and mundane tasks, all posed under the idea that adhering to rules and performing orders will make you a more “successful” soldier. It is precisely this advertised outcome that will often see children who misbehaved regularly be sent to a stricter school. Similarly, young rebellious teens are sent to the military to “whip them into shape”. These rehabilitation centers take in those who do not conform to a traditional model of society, or as Foucault calls them, “abnormal”, and reshapes them to be more docile and easier to manipulate into subjects.14 The architecture of these places generally has alarming similarities. They are generally stereotypically rigid in layout, with closely guarded spaces and fixed furniture (think children’s desks bolted to the ground). There were hard restrictions on which facilities were open to participants and which were out of bounds, deemed private to all but those in power, there were solid sturdy walls and sharp corners, with fencing meant to keep people from leaving the premise at random. At the fundamental scale, the shift from the panopticon to the disciplinary regime was one of shifts of power structure. The panopticon can be seen as a concept of mutual engagement, two sides of the power relationship confront each other and create a balance of control. This asymmetrical power dynamic began from the sovereigns, where power was taken through wars and force. However, now it is taken through strategies and tactics, games played by the few on the many, a game where the final outcome is to acquire power by whatever means necessary.

Slowly but surely, prisons began to change, alongside society and its use of control. What was formerly no more than a tiny space in which solitude, a lack of freedom and engineered boredom was the main focus of prisons, there now exists a new set of rules that began to shift how people were to behave. The exact scale of control changed drastically, from the former treatment of prisoners as a whole to the gradual separation of the mind from the body. New regimes and rules in prison are now designed to attack the mind, creating what Foucault called a more “docile” person.12 A subtleness went into the design of these rules and regimes, it was less about force and more about getting the body and mind to become adapt to certain binding rules, to adapt to a series of influences that would eventually become manifested within. If a man were to be woken up at 6 am every single day for 10 years, he would continue waking up at this time for the rest of his life. His mind and body have become accustomed to this way of living, and thus he is a slave of this simple rule.13 Current society tends to think of past decades as less reformed, more barbaric, and this mindset is applied to the previous way punishment regimes were run. Activities such as flagging and simple confinement are understood to be savage behaviors, as individuals of power believed that reform should come from the mind, not the body. More “enlightened” thinkers sought to develop ways to create a more docile and safe society, and thus the discipline regime was pushed to be incorporated into other facilities. The most notable ones are schools and militaries. This concept is not hard to see in the current context, as both schools and militaries drill into individuals the importance of rules and discipline. Young children are expected to bury their instincts to explore and instead must sit quietly and obey all the rules of their teacher. Similarly, militaries are even more strict when it comes to rigid timetables and mundane tasks, all posed under the idea that adhering to rules and performing orders will make you a more “successful” soldier. It is precisely this advertised outcome that will often see children who misbehaved regularly be sent to a stricter school. Similarly, young rebellious teens are sent to the military to “whip them into shape”. These rehabilitation centers take in those who do not conform to a traditional model of society, or as Foucault calls them, “abnormal”, and reshapes them to be more docile and easier to manipulate into subjects.14 The architecture of these places generally has alarming similarities. They are generally stereotypically rigid in layout, with closely guarded spaces and fixed furniture (think children’s desks bolted to the ground). There were hard restrictions on which facilities were open to participants and which were out of bounds, deemed private to all but those in power, there were solid sturdy walls and sharp corners, with fencing meant to keep people from leaving the premise at random. At the fundamental scale, the shift from the panopticon to the disciplinary regime was one of shifts of power structure. The panopticon can be seen as a concept of mutual engagement, two sides of the power relationship confront each other and create a balance of control. This asymmetrical power dynamic began from the sovereigns, where power was taken through wars and force. However, now it is taken through strategies and tactics, games played by the few on the many, a game where the final outcome is to acquire power by whatever means necessary.

Modern Surveillance in a Modern World

Capitalism is not a new concept. Lots of current issues in society can be considered as a direct result of capitalism, as its fundamental definition puts profit at the forefront of all that is deemed to be important, rendering humanity as second-tier considerations.15 People have always been exploited for the sake of profit, such as underpaid labor, class exploitation. These have all been around since the beginning of capitalism in the 17th century.16 However, as technology advances, there is a new form of capitalism on the rise, one defined as Surveillance Capitalism. To understand surveillance Capitalism, we must first consider Zygmund Bauman’s concept of modernity.

Liquid Modernity

Bauman coins the current period in society as a liquid modernity, one that is plastic and fluid compared to past periods of modernity. He claims that society is heading towards a phenomenon of fragility and vulnerability, one pushed by a steadily driven economic globalization.17 The push for a liquid state comes from the need for a neoliberal economic system, one that can freely operate in a society without a solid structure norm. This leads to the phenomenon of having everything be an economic potential – everything from religion to food can be marketed and sold to consumers, each element of society is a market piece.18 As the rules and regulations that generally impede capitalism are removed, corporations become the new conglomerate of mega-companies become the new sovereign of this globalized world. The concept of liquid also defines a new understanding of the individual in this state of modernity. If capitalism must sell to individuals to continue existing, then the fundamental status of each person is rendered as an individual solitary consumer. The identity of a holistic or collective grouping of our lives are erased, social and cultural bonds are dissolved, everyone is freed from the norms of society. However, as much as this freedom sounds enticing, it also leads to the uncertainty and fragility of a liquid state, as individuals are given freedom but also are demanded to be adaptable and non-conforming, to survive in such a rapidly changing society. As Bauman states, the shift in power control is the fundamental reason for this liquid state, stemming from the separation of power and politics.19 Politicians and governments are no longer the sole members who possess the power to change society, it has now also fallen into the hands of other aspects of our lives, from cyberspace to giant corporations. There is no one man in charge, and as a result, the unpredictability of society renders it a non-solid state. Such is the new state of surveillance and control.

Pharmacopornographic Regime

Beatriz Preciado also discusses the transition from a disciplinary regime before the 1900s to the current new regime of control. The disciplinary one, as he calls biopower, is a “tentacular and collective utopia of national health and reproduction connected to a series of dystopic confining institutions for the normalization of the body and subjectivity.”20 So, architecture, in this regime, is less so a virtual representation, but something that functions as a political vessel to physically create, morph, and reshape bodies to fit into a structured norm. One example Preciado gives is the birth of modern hospitals in France, the most explicit example of the study of architecture as a governmental technique. The layout of the hospital is one that represents a spatialization of medical knowledge and power, a physical manifestation of the technology and skills used in the disciplinary regime, a power of subjectivation.21

Capitalism is not a new concept. Lots of current issues in society can be considered as a direct result of capitalism, as its fundamental definition puts profit at the forefront of all that is deemed to be important, rendering humanity as second-tier considerations.15 People have always been exploited for the sake of profit, such as underpaid labor, class exploitation. These have all been around since the beginning of capitalism in the 17th century.16 However, as technology advances, there is a new form of capitalism on the rise, one defined as Surveillance Capitalism. To understand surveillance Capitalism, we must first consider Zygmund Bauman’s concept of modernity.

Liquid Modernity

Bauman coins the current period in society as a liquid modernity, one that is plastic and fluid compared to past periods of modernity. He claims that society is heading towards a phenomenon of fragility and vulnerability, one pushed by a steadily driven economic globalization.17 The push for a liquid state comes from the need for a neoliberal economic system, one that can freely operate in a society without a solid structure norm. This leads to the phenomenon of having everything be an economic potential – everything from religion to food can be marketed and sold to consumers, each element of society is a market piece.18 As the rules and regulations that generally impede capitalism are removed, corporations become the new conglomerate of mega-companies become the new sovereign of this globalized world. The concept of liquid also defines a new understanding of the individual in this state of modernity. If capitalism must sell to individuals to continue existing, then the fundamental status of each person is rendered as an individual solitary consumer. The identity of a holistic or collective grouping of our lives are erased, social and cultural bonds are dissolved, everyone is freed from the norms of society. However, as much as this freedom sounds enticing, it also leads to the uncertainty and fragility of a liquid state, as individuals are given freedom but also are demanded to be adaptable and non-conforming, to survive in such a rapidly changing society. As Bauman states, the shift in power control is the fundamental reason for this liquid state, stemming from the separation of power and politics.19 Politicians and governments are no longer the sole members who possess the power to change society, it has now also fallen into the hands of other aspects of our lives, from cyberspace to giant corporations. There is no one man in charge, and as a result, the unpredictability of society renders it a non-solid state. Such is the new state of surveillance and control.

Pharmacopornographic Regime

Beatriz Preciado also discusses the transition from a disciplinary regime before the 1900s to the current new regime of control. The disciplinary one, as he calls biopower, is a “tentacular and collective utopia of national health and reproduction connected to a series of dystopic confining institutions for the normalization of the body and subjectivity.”20 So, architecture, in this regime, is less so a virtual representation, but something that functions as a political vessel to physically create, morph, and reshape bodies to fit into a structured norm. One example Preciado gives is the birth of modern hospitals in France, the most explicit example of the study of architecture as a governmental technique. The layout of the hospital is one that represents a spatialization of medical knowledge and power, a physical manifestation of the technology and skills used in the disciplinary regime, a power of subjectivation.21

So, on the next evolution path of power regimes, Preciado brings forth a new concept, one morphed from the three main tools used in this new society – pharmaceuticals, pornography, and graphics and media. The biopower techniques have slowly mutated to adapt to a new emerging society, one that is filled with technology, social media, and the wildest drugs imaginable, thus, the elements of a controllable individual extend to the body, sex, race, and sexuality.22 Instead of the power punishing you or disciplining you after you have been deemed uncontrollable, the dynamic shifts completely. You are designed, created, and conditioned from the moment of birth, reducing the risk of anomalies, and more importantly, the tangible weapons of control become invisible, creating the illusion that there never was anyone controlling you in the first place. The human body becomes a “clip-on port for biopolitical technologies”, and in turn, architecture becomes “night-of-the-living-dead”.23 It is lifeless, thoughtless, meaningless, and exists only to serve the purpose of control, without contempt for the purpose of the individual. If the body, sex, race, soul, is the new target of control, and the weapons used are micro, unseen, intangible, and invisible, then it only makes sense that as the regime mutates to be micro, so too does architecture. “In the pharmacopornographic regime, the body no longer inhabits disciplinary places but is now inhabited by them. Architecture exists in us.”24 In such a society, one can argue that the very idea of architecture becomes porn, the idea of property ownership, the fancy dazzling images of houses and apartments on Instagram, the millions of articles on Archdaily and Dezeen, are these not pornography intended to entice and lead us to think that these are objects of desire that we crave, a glittering simulation that promises a better life.

![Figure 3. Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era]()

Whether it’s Trump's gold dazzling apartment in New York or IKEA’s more modest living room sets, architecture becomes part of the porno weapon in a pharmacopornographic society, just another enticing object to lead you to follow the path designed by the power.

Surveillance Capitalism

Similar to Bauman’s concept of Liquid Modernity, Shoshana Zuboff discusses the term information civilization, one that entangles the very basic question of knowledge, authority, and power, tracing their roots to the necessities of daily life and every form of social participation.25 This type of surveillance capitalism renders all human experience as free, raw material for translation into behavioral data, fed into “machine intelligence” and fabricated into prediction products that anticipate and design your future move.26 Like a skilled gardener, capitalism waters and watches all the plants, nudging, coaxing, tuning, and herding until all the flowers grow to conform to his exact satisfaction – a profitable outcome.27 “At its core, surveillance capitalism is parasitic and self-referential. It revives Karl Marx’s old image of capitalism as a vampire that feeds on labor, but with an unexpected turn. Instead of labor, surveillance capitalism feeds on every aspect of every human’s experience.”28 What’s perhaps worse, is the fact that society is unaware of this turn of control, individuals are taught that they’re not worth watching, and thus willingly pay for our domination, through smart speakers, amazon accounts, phones, and smart TVs, all the gadgets we surround ourselves with. Perhaps the most visible evidence of this is the smart cities concept.

Whether it’s Trump's gold dazzling apartment in New York or IKEA’s more modest living room sets, architecture becomes part of the porno weapon in a pharmacopornographic society, just another enticing object to lead you to follow the path designed by the power.

Surveillance Capitalism

Similar to Bauman’s concept of Liquid Modernity, Shoshana Zuboff discusses the term information civilization, one that entangles the very basic question of knowledge, authority, and power, tracing their roots to the necessities of daily life and every form of social participation.25 This type of surveillance capitalism renders all human experience as free, raw material for translation into behavioral data, fed into “machine intelligence” and fabricated into prediction products that anticipate and design your future move.26 Like a skilled gardener, capitalism waters and watches all the plants, nudging, coaxing, tuning, and herding until all the flowers grow to conform to his exact satisfaction – a profitable outcome.27 “At its core, surveillance capitalism is parasitic and self-referential. It revives Karl Marx’s old image of capitalism as a vampire that feeds on labor, but with an unexpected turn. Instead of labor, surveillance capitalism feeds on every aspect of every human’s experience.”28 What’s perhaps worse, is the fact that society is unaware of this turn of control, individuals are taught that they’re not worth watching, and thus willingly pay for our domination, through smart speakers, amazon accounts, phones, and smart TVs, all the gadgets we surround ourselves with. Perhaps the most visible evidence of this is the smart cities concept.

A Future of Surveillance – the Smart Regime

From Smart Devices to Smart Cities

As people become accustomed to a work/study life at home (this shift, one can argue, started happening even pre-COVID), their digital setup slowly increases. Starting with laptops and pcs, and then comes the need to accessorize and expand the capabilities of these basic digital devices. Slight conveniences of life are being advertised as being the future of home living, and all you would have to sacrifice is your data being collected by whatever company is selling you these smart devices, and to some, that may not seem like a big deal. This phenomenon not only happens at the small scale, it is also being applied to the city scale. For cities, larger smart tactics promise more urban innovations to solve uniquely urban problems, things such as traffic control, waste management, housing, transit, etc. However, the very idea of being “smart” is an extremely relative concept, as for cities, being smart is about faster smoother functioning and attracting money and technology. For the technology companies, being smart is about a method of capturing the rising value of data flow, the next big evolution in knowledge control. Data can be used to either directly monetize behavior insights, or indirectly to control and persuade services from the public.29

Sidewalk Labs

In 2017, Waterfront Toronto sent out a request for proposals to develop a formerly industrial piece of land on the Toronto waterfront. They wanted to find an “innovation and funding partner”, one who can help transform the land into a shiny new development along the waterfront.30 At that time, Sidewalk Labs was a relatively new company, but one that had the backing of Alphabet and Google, making it a promising partner with solid credentials. The Sidewalk Labs Toronto project was widely advertised, pushed to the front page of every paper, and it seemed that for a while this was going to be a glittery new project that would shape Toronto as one of the most innovative cities of the world. However, things quickly went sour and in May of 2020, the project was announced to be canceled, leaving the large site in Portlands once again abandoned. The following is a breakdown of what may have gone wrong.

![Figure 4. Sidwalk Labs sketch]()

On the political side, an issue with the democratic governance in Canada is that the public is largely unaware of non-government organizations who have power over local matters despite being a non-municipal body.31 They often play a critical role in shaping cities, and Waterfront Toronto (WT) is no different. Until the announcement of the Sidewalk project, WT was not an organization that appeared on anyone’s radar, and so it was a shock to hear of such a massive project being led by a local organization.32 Furthermore, Sidewalk Labs quickly took over the initiative and became the face of the project, while WT retreated to the side. This left the public confused, and not to mention a little wary of dealing with an unknown entity, especially one that was foreign to Canada and had the shadow of Google behind their back. Distrust already runs in society, especially towards mega conglomerates who are taking over all aspects of everyday objects. Brands such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are near impossible to avoid. As such, it was not a surprise that Toronto was uncomfortable with the idea of a residential project in the total grasp of Google, spurring a “techlash”33 towards the entire project. A challenge to the fundamental right of privacy, one headed by a faceless conglomerate no less, forces individuals to give up their exclusive rights to not only decide to give up data but also the right to decide what the data will be used for.34

From Smart Devices to Smart Cities

As people become accustomed to a work/study life at home (this shift, one can argue, started happening even pre-COVID), their digital setup slowly increases. Starting with laptops and pcs, and then comes the need to accessorize and expand the capabilities of these basic digital devices. Slight conveniences of life are being advertised as being the future of home living, and all you would have to sacrifice is your data being collected by whatever company is selling you these smart devices, and to some, that may not seem like a big deal. This phenomenon not only happens at the small scale, it is also being applied to the city scale. For cities, larger smart tactics promise more urban innovations to solve uniquely urban problems, things such as traffic control, waste management, housing, transit, etc. However, the very idea of being “smart” is an extremely relative concept, as for cities, being smart is about faster smoother functioning and attracting money and technology. For the technology companies, being smart is about a method of capturing the rising value of data flow, the next big evolution in knowledge control. Data can be used to either directly monetize behavior insights, or indirectly to control and persuade services from the public.29

Sidewalk Labs

In 2017, Waterfront Toronto sent out a request for proposals to develop a formerly industrial piece of land on the Toronto waterfront. They wanted to find an “innovation and funding partner”, one who can help transform the land into a shiny new development along the waterfront.30 At that time, Sidewalk Labs was a relatively new company, but one that had the backing of Alphabet and Google, making it a promising partner with solid credentials. The Sidewalk Labs Toronto project was widely advertised, pushed to the front page of every paper, and it seemed that for a while this was going to be a glittery new project that would shape Toronto as one of the most innovative cities of the world. However, things quickly went sour and in May of 2020, the project was announced to be canceled, leaving the large site in Portlands once again abandoned. The following is a breakdown of what may have gone wrong.

On the political side, an issue with the democratic governance in Canada is that the public is largely unaware of non-government organizations who have power over local matters despite being a non-municipal body.31 They often play a critical role in shaping cities, and Waterfront Toronto (WT) is no different. Until the announcement of the Sidewalk project, WT was not an organization that appeared on anyone’s radar, and so it was a shock to hear of such a massive project being led by a local organization.32 Furthermore, Sidewalk Labs quickly took over the initiative and became the face of the project, while WT retreated to the side. This left the public confused, and not to mention a little wary of dealing with an unknown entity, especially one that was foreign to Canada and had the shadow of Google behind their back. Distrust already runs in society, especially towards mega conglomerates who are taking over all aspects of everyday objects. Brands such as Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are near impossible to avoid. As such, it was not a surprise that Toronto was uncomfortable with the idea of a residential project in the total grasp of Google, spurring a “techlash”33 towards the entire project. A challenge to the fundamental right of privacy, one headed by a faceless conglomerate no less, forces individuals to give up their exclusive rights to not only decide to give up data but also the right to decide what the data will be used for.34

On the technological side, there is no doubt the plans of Sidewalk Labs were one of the most innovative proposals yet. Titled “the world’s first neighborhood built from the internet up”, the vision of the community was extremely ambitious.35 The proposal was supposed to have state-of-the-art sustainability tactics, autonomous vehicles, sensor-based surveillance, and data-driven responsive services, all promoting the visions of a city of the future.36 However, all these accessible services came with a price – the price of handing over your life to Google. Should people be allowed to be tracked in public realms in the first place? Who stands to benefit from such tracking and data collection? Should we even allow our entire lives to be, as Bauman says of modernity, be commodified as an item, to be put into the pool of the market and sold as a commodity, or should we set limits to what is marketable and what is not.37 The community, at the end of the day, is no more than a series of domestic homes. If the very idea of a home, a private domain, one which is fundamentally composed of trust, simplicity, sovereign of the individual, and inviolability of personal space, was rendered obsolete, then what becomes of our lives?38 Urban innovations are, when set out to solve urban problems, always a positive for the city. However, privatized urban innovations can be cause for concern, especially when the hidden agenda of these proposals are not released to the public. A step further than the pharmacopornographic regimes, this new form of surveillance regime not only designs and controls society through the medicating, desiring, and numbing of subjects, but also through collecting data from individuals to better upgrade and perfect their methods. What all previous regimes lacked in the ability to gather knowledge and intel; this new “smart” control system perfected. Aided with the use of artificial intelligence and rapid supercomputers, the processing of big data could lead to unlimited potential. As Bauman mentioned, the liquid of society comes from a separation of power and government, and here, is where the power is dispersed from. If corporations like Google can collect more data on individuals than governments, then whosoever holds the most data is the one with more power. In the panopticon, the guards are in control because they hold the access to information in terms of who is being surveilled. In a smart city, the forces behind the technology become the knowledgeable guards, the ones who can control what and who and when they see.

What are the outcomes?

How does architecture fit into this picture of a “smart” regime? As Sidewalk Labs portrays itself as a harmonious, beautifully rendered utopia, the streets are clean, the sidewalks are wide, the materials are sustainable and aesthetic, and thanks to the smart waste system, there is zero trash anywhere. However, it begs the question, is this city scheme designed based on humans and for humans, or is it a scheme that favors the ease of data collection above all else? If the fundamental goal of smart cities is to gather data, adapt, and upgrade to perfect themselves, then the architecture must be based on such foundations as well. It is less so a community for citizens, more a testbed for the newest automated technologies, a simulation that veils the true identity of surveillance. If reduced to a single item, the smart city is one giant machine, one that serves not the functions of humans, but simply the function of itself that it was programmed to do, with no discern regarding privacy and freedom.

So, what happens when architecture is designed for privacy? One particular building in Tokyo, designed by Satoru Hirota Architects, focused specifically on providing privacy for a single-family located in the heart of the city. Due to the density of Tokyo itself, and the fact that the lot faced a public street, the design played with the sense of distance and opening, minimizing the views inside from the front façade.

![Figure 2. House of Fluctuation, Toyko]()

Offset boxes with gaps were used to still provide light and ventilation within the house itself.39 However nice the interiors are designed, there is no doubt this is an attempt at sacrificing views and connections in exchange for a little privacy within the busy city, and this only deals with privacy on a physical note, ignoring completely the idea of digital privacy within the walls of the confined. Is this to be the future of architecture if paranoia of privacy reaches the masses? Are the likes of Philip Johnson’s Glass House to be forever a purely aesthetic and never practical design?

How does architecture fit into this picture of a “smart” regime? As Sidewalk Labs portrays itself as a harmonious, beautifully rendered utopia, the streets are clean, the sidewalks are wide, the materials are sustainable and aesthetic, and thanks to the smart waste system, there is zero trash anywhere. However, it begs the question, is this city scheme designed based on humans and for humans, or is it a scheme that favors the ease of data collection above all else? If the fundamental goal of smart cities is to gather data, adapt, and upgrade to perfect themselves, then the architecture must be based on such foundations as well. It is less so a community for citizens, more a testbed for the newest automated technologies, a simulation that veils the true identity of surveillance. If reduced to a single item, the smart city is one giant machine, one that serves not the functions of humans, but simply the function of itself that it was programmed to do, with no discern regarding privacy and freedom.

So, what happens when architecture is designed for privacy? One particular building in Tokyo, designed by Satoru Hirota Architects, focused specifically on providing privacy for a single-family located in the heart of the city. Due to the density of Tokyo itself, and the fact that the lot faced a public street, the design played with the sense of distance and opening, minimizing the views inside from the front façade.

Offset boxes with gaps were used to still provide light and ventilation within the house itself.39 However nice the interiors are designed, there is no doubt this is an attempt at sacrificing views and connections in exchange for a little privacy within the busy city, and this only deals with privacy on a physical note, ignoring completely the idea of digital privacy within the walls of the confined. Is this to be the future of architecture if paranoia of privacy reaches the masses? Are the likes of Philip Johnson’s Glass House to be forever a purely aesthetic and never practical design?

Conclusion

Through sovereign to disciplinary regimes, architecture continues to be a vessel for control, a solid physical state in which Foucault’s theories run. However, with the mutation of biopower to pharma-power, the boundary of exterior and interior control slowly dissolves, as does the architecture which binds us to society. Today, in the case of smart cities, architecture is no longer a representation of control and surveillance, as it is no longer even required to be such a tool. The technological advances of surveillance have successfully broken the “fourth wall” and settled into our bodies and minds, thus rendering the function of physical architecture back to its purest form, the form of shelter. Architecture itself no longer holds the propaganda, as the streams of controls have embedded themselves past the physical walls of a home, deep into our bodies and minds.

Through sovereign to disciplinary regimes, architecture continues to be a vessel for control, a solid physical state in which Foucault’s theories run. However, with the mutation of biopower to pharma-power, the boundary of exterior and interior control slowly dissolves, as does the architecture which binds us to society. Today, in the case of smart cities, architecture is no longer a representation of control and surveillance, as it is no longer even required to be such a tool. The technological advances of surveillance have successfully broken the “fourth wall” and settled into our bodies and minds, thus rendering the function of physical architecture back to its purest form, the form of shelter. Architecture itself no longer holds the propaganda, as the streams of controls have embedded themselves past the physical walls of a home, deep into our bodies and minds.

That is not to say that architecture is no longer important in the role of surveillance and control, but that it is merely a lot more complex and uncertain, as its role become fragile, just as the liquid state of modernity does. If architecture is no longer relevant as propaganda, then perhaps its aesthetic will no longer be determined by external power struggles, and can be free to be designed to only suit the individual and not the society. Or, perhaps, there will come a time when privacy becomes a thing of the past, and people will happily relinquish control over their data in exchange for a more pleasant peaceful life, no fear from the watching eyes of others. All

architecture, in that case, might be transparent and public, like Philip Johnson’s Glass House, a whole life on display to the world. Either way, the architecture of surveillance and control will change alongside society, and for better or worse, only time will tell.

Footnotes

- Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020).

-

“Are Your Phone Camera and Microphone Spying on You? | Dylan Curran,” The Guardian (Guardian News and Media, April 6, 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/06/phone-camera-microphone-spying.

- Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, “Part One: Torture. The body of the condemned” in Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020), page 38.

- Ibid, page 16.

- Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, “Part One: Torture. The spectacle of the scaffold” in Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020).

- G. Carrio et al., “About the Impossibility of Absolute State Sovereignty,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique (Springer Netherlands, January 1, 1965), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11196-013-9333-x.

- Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon: or the Inspection House (Whithorn: Anodos Books, 2017).

-

Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, “Part 3. Discipline - Panopticism,” in Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020).

- Ibid, page 231.

- Zygmunt Bauman, “Individuality” in Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018), page 42.

- Antonia Mackay and Susan Flynn, “The Panoptic City” in Surveillance, Architecture and Control Discourses on Spatial Culture (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019).

- Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, “Part 3. Discipline - Panopticism,” in Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020), page 237.

- Ibid, page 120.

- Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, “Part Three: Discipline – Docile Bodies” in Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020), page 147-192.

- Zygmunt Bauman, “Emancipation” in Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

-

McLEAN, Iain, and Alistair McMILLAN. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Zygmunt Bauman, “Community” in Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

- Ibid, “Individuality”

- Ibid.

- Preciado, Beatriz. "Architecture as a Practice of Biopolitical Disobedience." Log, no. 25 (2012): 124. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41765746.

-

Ibid 22.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, page 128.

- Preciado, Beatriz. "Architecture as a Practice of Biopolitical Disobedience." Log, no. 25 (2012): 130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41765746.

- Shoshana Zuboff, “The moat around the castle” in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), page 110-137

- Ibid, “Home or Exile in the Digital Future”, page 10-32

- Ibid, “The Elaboration of Surveillance Capitalism: Kidnap, Corner, Compete”, page 138-187

- Ibid

- Goodman, Ellen P. and Julia Powles. "urbanism Under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto." Fordham Law Review 88, no. 2 (2019): 457.

- Flynn, Alexandra, and Mariana Valverde. “Where The Sidewalk Ends: The Governance Of Waterfront Toronto’s Sidewalk Labs Deal.” Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 36 (September 18, 2019): 263–83. doi:10.22329/wyaj.v36i0.6425

- Flynn, Alexandra, and Mariana Valverde. “Where The Sidewalk Ends: The Governance Of Waterfront Toronto’s Sidewalk Labs Deal.” Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 36 (September 18, 2019): 266. doi:10.22329/wyaj.v36i0.6425.

- Ibid

- Doug Brake Robert D. Atkinson, “A Policymaker's Guide to the ‘Techlash’-What It Is and Why It's a Threat to Growth and Progress,” A Policymaker's Guide to the "Techlash"-What It Is and Why It's a Threat to Growth and Progress (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, October 28, 2019), https://itif.org/publications/2019/10/28/policymakers-guide-techlash.

- Shoshana Zuboff, “August 9, 2011: Setting the Stage for Surveillance Capitalism” in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), page 34-70

-

Ellen P. Goodman; Julia Powles, "Urbanism under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto," Fordham Law Review 88, no. 2 (November 2019): 457-498

-

Ibid

-

Ibid

-

Shoshana Zuboff, “Home or Exile in the Digital Future” in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (New York: PublicAffairs, 2020), page 10-32

- Designing for Privacy: Architecture in the Surveillance Age - Design & Build Review: Issue 55: April 2020,” Design & Build Review | Issue 55 | April 2020, May 5, 2020.

Bibliography

“Are Your Phone Camera and Microphone Spying on You? | Dylan Curran.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, April 6, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/06/phone-camera-microphone-spying.

“Designing for Privacy: Architecture in the Surveillance Age - Design & Build Review: Issue 55: April 2020,” Design & Build Review | Issue 55 | April 2020, May 5, 2020

Flynn, Alexandra, and Mariana Valverde. “Where The Sidewalk Ends: The Governance Of Waterfront Toronto’s Sidewalk Labs Deal.” Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 36 (September 18, 2019): 263–83. doi:10.22329/wyaj.v36i0.6425.

G. Carrio et al., “About the Impossibility of Absolute State Sovereignty,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique (Springer Netherlands, January 1, 1965), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11196-013-9333-x.

Goodman, Ellen P. and Julia Powles. "urbanism Under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto." Fordham Law Review 88, no. 2 (2019): 457.

Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon: or the Inspection House (Whithorn: Anodos Books, 2017).

Mackay, Antonia, and Susan Flynn. Surveillance, Architecture and Control Discourses on Spatial Culture. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019.

McLEAN, Iain, and Alistair McMILLAN. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020).

Preciado, Beatriz. "Architecture as a Practice of Biopolitical Disobedience." Log, no. 25 (2012): 121-34. Accessed December 15, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41765746.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2020.

Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

“Are Your Phone Camera and Microphone Spying on You? | Dylan Curran.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, April 6, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/06/phone-camera-microphone-spying.

“Designing for Privacy: Architecture in the Surveillance Age - Design & Build Review: Issue 55: April 2020,” Design & Build Review | Issue 55 | April 2020, May 5, 2020

Flynn, Alexandra, and Mariana Valverde. “Where The Sidewalk Ends: The Governance Of Waterfront Toronto’s Sidewalk Labs Deal.” Windsor Yearbook of Access to Justice 36 (September 18, 2019): 263–83. doi:10.22329/wyaj.v36i0.6425.

G. Carrio et al., “About the Impossibility of Absolute State Sovereignty,” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue internationale de Sémiotique juridique (Springer Netherlands, January 1, 1965), https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11196-013-9333-x.

Goodman, Ellen P. and Julia Powles. "urbanism Under Google: Lessons from Sidewalk Toronto." Fordham Law Review 88, no. 2 (2019): 457.

Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon: or the Inspection House (Whithorn: Anodos Books, 2017).

Mackay, Antonia, and Susan Flynn. Surveillance, Architecture and Control Discourses on Spatial Culture. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019.

McLEAN, Iain, and Alistair McMILLAN. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020).

Preciado, Beatriz. "Architecture as a Practice of Biopolitical Disobedience." Log, no. 25 (2012): 121-34. Accessed December 15, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41765746.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. New York: PublicAffairs, 2020.

Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2018).

Figure 1. Chng, Pamela. “The Soul Is the Prison of the Body.” Medium. Medium, May 7, 2018. https://pamchng.medium.com/the-soul-is-the-prison-of-the-body-bf8ef943fe4.

Figure 2. Sciences, Posted by Sunderland Social. “Is Everywhere a Panopticon?” Social Sciences Blog, September 21, 2018. https://sunderlandsocialsciences.wordpress.com/2018/09/21/is-everywhere-a-panopticon/.

Figure 3. “Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era - Http://T.co/bs7o2h2eII Pic.twitter.com/lA9WTtelUe.” Twitter. Twitter, November 26, 2014. https://twitter.com/aaaarg/status/537592744588636161.

Figure 4. Torontoist. “Civic Tech: A List of Questions We'd like Sidewalk Labs to Answer.” Torontoist, November 13, 2017. https://torontoist.com/2017/10/civic-tech-list-questions-wed-like-sidewalk-labs-answer/.

Figure 5. 2016. "Gallery of House of Fluctuations / Satoru Hirota Architects." ArchDaily. October 09. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.archdaily.com/796882/house-of-fluctuations-satoru-hirota-architects/57f6f9afe58ece756100003f-house-of-fluctuations-satoru-hirota-architects-photo.

Figure 2. Sciences, Posted by Sunderland Social. “Is Everywhere a Panopticon?” Social Sciences Blog, September 21, 2018. https://sunderlandsocialsciences.wordpress.com/2018/09/21/is-everywhere-a-panopticon/.

Figure 3. “Beatriz Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era - Http://T.co/bs7o2h2eII Pic.twitter.com/lA9WTtelUe.” Twitter. Twitter, November 26, 2014. https://twitter.com/aaaarg/status/537592744588636161.

Figure 4. Torontoist. “Civic Tech: A List of Questions We'd like Sidewalk Labs to Answer.” Torontoist, November 13, 2017. https://torontoist.com/2017/10/civic-tech-list-questions-wed-like-sidewalk-labs-answer/.

Figure 5. 2016. "Gallery of House of Fluctuations / Satoru Hirota Architects." ArchDaily. October 09. Accessed December 16, 2020. https://www.archdaily.com/796882/house-of-fluctuations-satoru-hirota-architects/57f6f9afe58ece756100003f-house-of-fluctuations-satoru-hirota-architects-photo.