Nicole Burdynewicz

A Low Energy and Sustainable Retrofit of a 100 Year-Old Italian Building

In this studio, the aim of the final design project was to renovate an existing building in a sustainable way in terms of energy, materials, water, and social benefits. Net zero was aimed for. This was done using energy modeling software and a good understanding of climate, needs and sustainability in general. The building that was chosen was the villa of Andrea Camilleri, a notable Italian author who recently passed away. The foundation in his name was looking to renovate and add programming such as an event space, office, and live-in writer's studio.

View vitural walkthrough HERE.

A Low Energy and Sustainable Retrofit of a 100 Year-Old Italian Building

In this studio, the aim of the final design project was to renovate an existing building in a sustainable way in terms of energy, materials, water, and social benefits. Net zero was aimed for. This was done using energy modeling software and a good understanding of climate, needs and sustainability in general. The building that was chosen was the villa of Andrea Camilleri, a notable Italian author who recently passed away. The foundation in his name was looking to renovate and add programming such as an event space, office, and live-in writer's studio.

View vitural walkthrough HERE.

The Camilleri Foundation, located in Rome, Italy, is looking to renovate the house of Andrea Camilleri, who has recently passed away. Camilleri was a notable author in Italy and worldwide.

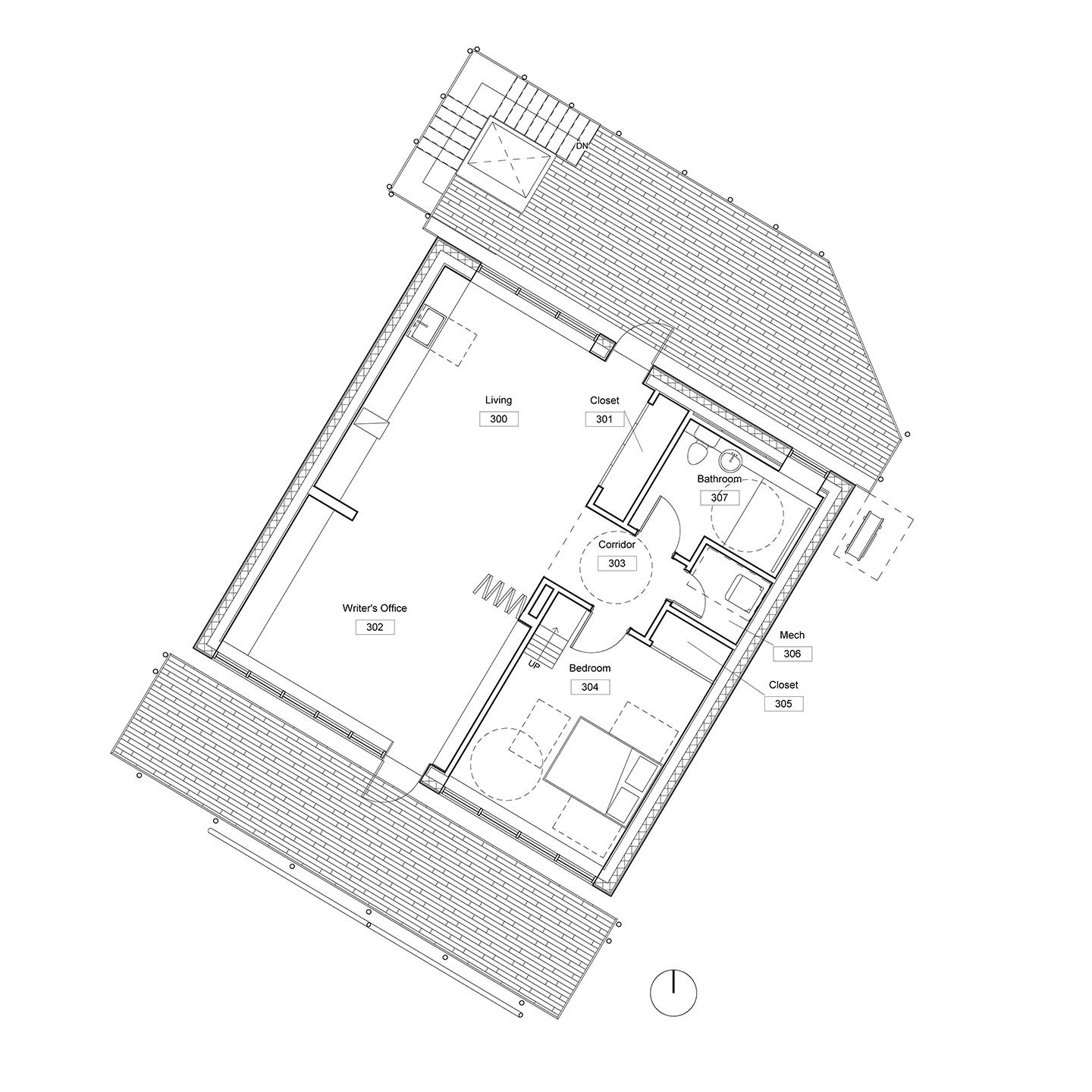

The renovation aims to make the building more sustainable and provide new program. Sustainability in this case includes not only ecological sustainability but also social and financial. The new program includes an event space on the ground floor, office space on the first floor, a guest writer’s studio on the second floor, and a proposed third floor for a second writer’s studio.

The climate in Rome is Mediterranean where the cooling season is dominant. Therefore, northern light and much shading was ideal, as well as natural ventilation. The energy grid of Italy is also natural gas-heavy and so energy generation was prioritized.

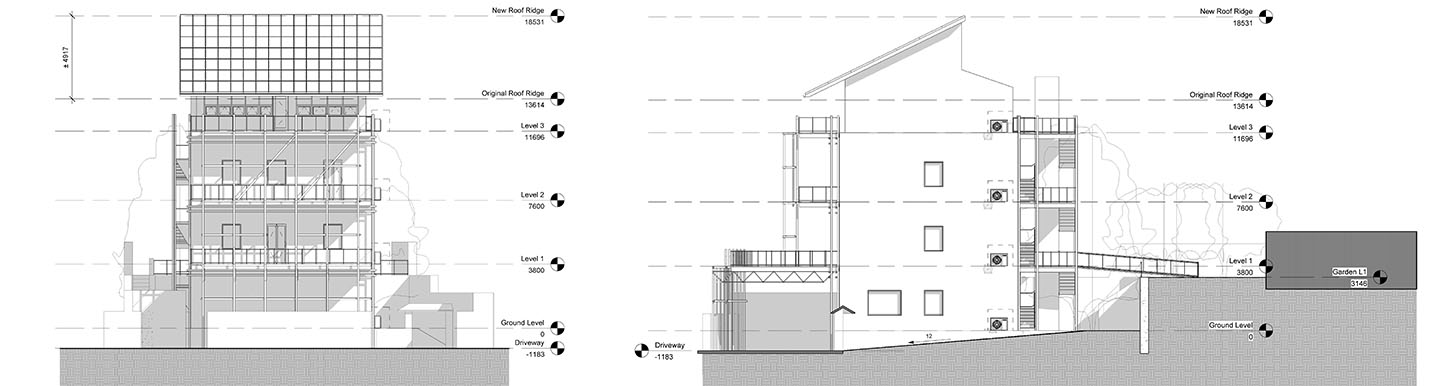

Energy efficiency was addressed through adding insulation, which was entirely lacking in the existing. The heavy limestone and brick walls were over-clad with mineral wool insulation with a stucco finish to match the context. The roof was replaced with an additional floor that would undertake many sustainable features to improve the building as a whole.

The addition of the third floor provides a means for generating electricity via solar panels, collecting rainwater for gardening, while allowing for a completely accessible unit, which is socially sustainable.

Along with an exterior platform lift, the third floor provides accessibility for not only people with physical disabilities but is also family friendly.

The front and rear scaffold structures provide shaded exterior space and pre-cools air for natural ventilation through evapotranspiration. The scaffold material, as well as other building materials can be easily salvaged from the surrounding area and is therefore economically and ecologically sustainable. It also allows for customization and further reuse. The interior doors and windows are reused from the renovation so the materials do not leave the site.

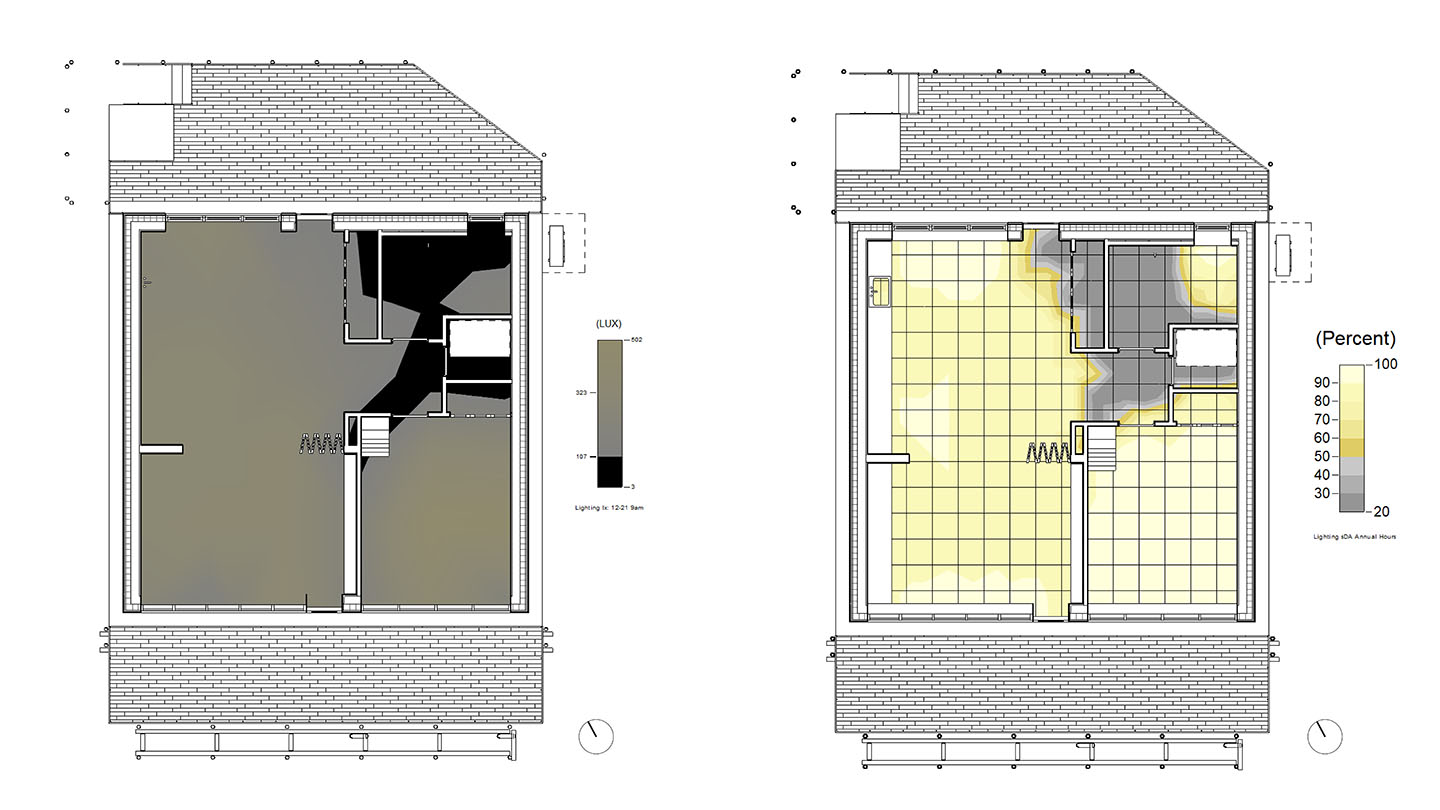

The third floor also requires very little artificial light through strategic daylighting and completely eliminates glare, as seen in the daylight autonomy study and illuminance study.

Tools used for analysis include DesignBuilder for energy modeling, WUFI for moisture transfer, and Revit’s Insight for solar energy analysis and daylighting.

Design Process and Features:

The design process focused on climate-specific design, all facets of sustainability, and minimizing the interventions to the existing structure. This being said, two major design moves were chosen based on their ability to multitask sustainable features and were designed to have a large positive effect on all aspects of sustainability.

The renovation includes two major design moves: a third floor addition and freestanding scaffold decks in the front and back of the building. The third floor addition incorporates a wide variety of sustainable features including solar panels, natural cross-ventilation, water harvesting, and diffuse daylighting with no glare. It is also a space that improves the overall social sustainability by being completely barrier free and family friendly. Since the lower floors are limiting in terms of mobility, it was imperative to include a wider variety of people as writers are not limited to able-bodied people with minimal family obligations.

The decks on the front and back provide an extensive amount of outdoor space in addition to the large backyard. These, however, also provide shade to the building, more private outdoors space and therefore more options to the occupants, and can act as a trellis to foster both climbing plants and space for urban agriculture. The evapotranspiration that the plants produce cools the space and makes the south facade much more habitable. They also provide privacy, some acoustic separation, and pre-cools air for natural ventilation.

The back deck was outfitted with a new exterior accessible lift and wrap-around stairs. A ramped bridge was also provided for easy access to the upper garden. For book readings and events, the back decks also provide ample space and views and can act as tiered seating in this way.

Other interventions include the addition of a vapour-permeable air barrier that would be liquid-applied to the brick surface. On top of this, mineral wool EIFS would be applied to insulate the whole building above the foundation. The stucco finish would match well with the surrounding rendered buildings.

To further improve the envelope, all windows and doors would be replaced with either wood or fibreglass double-glazed windows with a low solar heat gain coefficient. Both fibreglass and wood have good thermal properties and, since the climate is predominantly cooling, the low heat gain would improve the thermal comfort.

With the building vastly more airtight, a full HVAC system is required. Air-source heat pumps are proposed for both the boilers and space conditioning units, with a ventilation system with a heat exchanger. Having the boiler run using a heat pump is especially beneficial in the summer months by directing heat energy from the habitable spaces to the water. This is very efficient as it doubles up on usage while taking advantage of the ultra-efficient nature of heat pumps. Each floor would have a standalone system for optimal occupant comfort between floors. The system would also shut off if natural cross-ventilation is preferred.

![]()

![]()

The design process focused on climate-specific design, all facets of sustainability, and minimizing the interventions to the existing structure. This being said, two major design moves were chosen based on their ability to multitask sustainable features and were designed to have a large positive effect on all aspects of sustainability.

The renovation includes two major design moves: a third floor addition and freestanding scaffold decks in the front and back of the building. The third floor addition incorporates a wide variety of sustainable features including solar panels, natural cross-ventilation, water harvesting, and diffuse daylighting with no glare. It is also a space that improves the overall social sustainability by being completely barrier free and family friendly. Since the lower floors are limiting in terms of mobility, it was imperative to include a wider variety of people as writers are not limited to able-bodied people with minimal family obligations.

The decks on the front and back provide an extensive amount of outdoor space in addition to the large backyard. These, however, also provide shade to the building, more private outdoors space and therefore more options to the occupants, and can act as a trellis to foster both climbing plants and space for urban agriculture. The evapotranspiration that the plants produce cools the space and makes the south facade much more habitable. They also provide privacy, some acoustic separation, and pre-cools air for natural ventilation.

The back deck was outfitted with a new exterior accessible lift and wrap-around stairs. A ramped bridge was also provided for easy access to the upper garden. For book readings and events, the back decks also provide ample space and views and can act as tiered seating in this way.

Other interventions include the addition of a vapour-permeable air barrier that would be liquid-applied to the brick surface. On top of this, mineral wool EIFS would be applied to insulate the whole building above the foundation. The stucco finish would match well with the surrounding rendered buildings.

To further improve the envelope, all windows and doors would be replaced with either wood or fibreglass double-glazed windows with a low solar heat gain coefficient. Both fibreglass and wood have good thermal properties and, since the climate is predominantly cooling, the low heat gain would improve the thermal comfort.

With the building vastly more airtight, a full HVAC system is required. Air-source heat pumps are proposed for both the boilers and space conditioning units, with a ventilation system with a heat exchanger. Having the boiler run using a heat pump is especially beneficial in the summer months by directing heat energy from the habitable spaces to the water. This is very efficient as it doubles up on usage while taking advantage of the ultra-efficient nature of heat pumps. Each floor would have a standalone system for optimal occupant comfort between floors. The system would also shut off if natural cross-ventilation is preferred.

Energy Consumption:

Energy simulations were conducted using DesignBuilder, which is a graphic interface for EnergyPlus. The energy consumption of the proposed, including the additional floor, the energy consumption came to approximately 147 kWh/m2/year. This includes the cooling demand, however properly modelling natural ventilation would require both more research and experimentation within the software and, due to time constraints, cannot be relied upon. Additionally, the micro-climate that the plants create was also not accounted for. Finally, the efficiency of the heat pump system was also difficult to model and would have required some more time to better understand the process to build custom HVAC systems to test. These uncertainties would bring the number for energy consumption down and could hit the target 111.5 kWh/m2 that the solar panels can generate, especially when considering the COP of the heat pump.

Looking at the other energy uses the solar power would easily cover the almost 11,000 kWh that is used for lighting and equipment with over 20,000 kWh left over for heating and cooling. With proper modelling and integration of all passive strategies, this number could very well prove to be net zero.

Energy simulations were conducted using DesignBuilder, which is a graphic interface for EnergyPlus. The energy consumption of the proposed, including the additional floor, the energy consumption came to approximately 147 kWh/m2/year. This includes the cooling demand, however properly modelling natural ventilation would require both more research and experimentation within the software and, due to time constraints, cannot be relied upon. Additionally, the micro-climate that the plants create was also not accounted for. Finally, the efficiency of the heat pump system was also difficult to model and would have required some more time to better understand the process to build custom HVAC systems to test. These uncertainties would bring the number for energy consumption down and could hit the target 111.5 kWh/m2 that the solar panels can generate, especially when considering the COP of the heat pump.

Looking at the other energy uses the solar power would easily cover the almost 11,000 kWh that is used for lighting and equipment with over 20,000 kWh left over for heating and cooling. With proper modelling and integration of all passive strategies, this number could very well prove to be net zero.