2021 Year End Show

Ryerson’s Department of Architectural Science encourages its students to test boundaries, explore new possibilities, and apply their skill to prevailing issues present within their evolving surroundings. Our second virtual Year End Show presents the culmination of the 2020/21 academic term, showcasing the impressive and cutting-edge works of our top students in all four years of study and at the graduate level.

2021 Year End Show Sponsors:

AZURE

Montgomery Sisam

Pella Architectural Solutions

RAW Design

Baldassarra Architects

All Projects ︎︎︎

2021 Year End Show

Ryerson’s Department of Architectural Science encourages its students to test boundaries, explore new possibilities, and apply their skill to prevailing issues present within their evolving surroundings. Our second virtual Year End Show presents the culmination of the 2020/21 academic term, showcasing the impressive and cutting-edge works of our top students in all four years of study and at the graduate level.

2021 Year End Show Sponsors:

AZURE

Montgomery Sisam

Pella Architectural Solutions

RAW Design

Baldassarra Architects

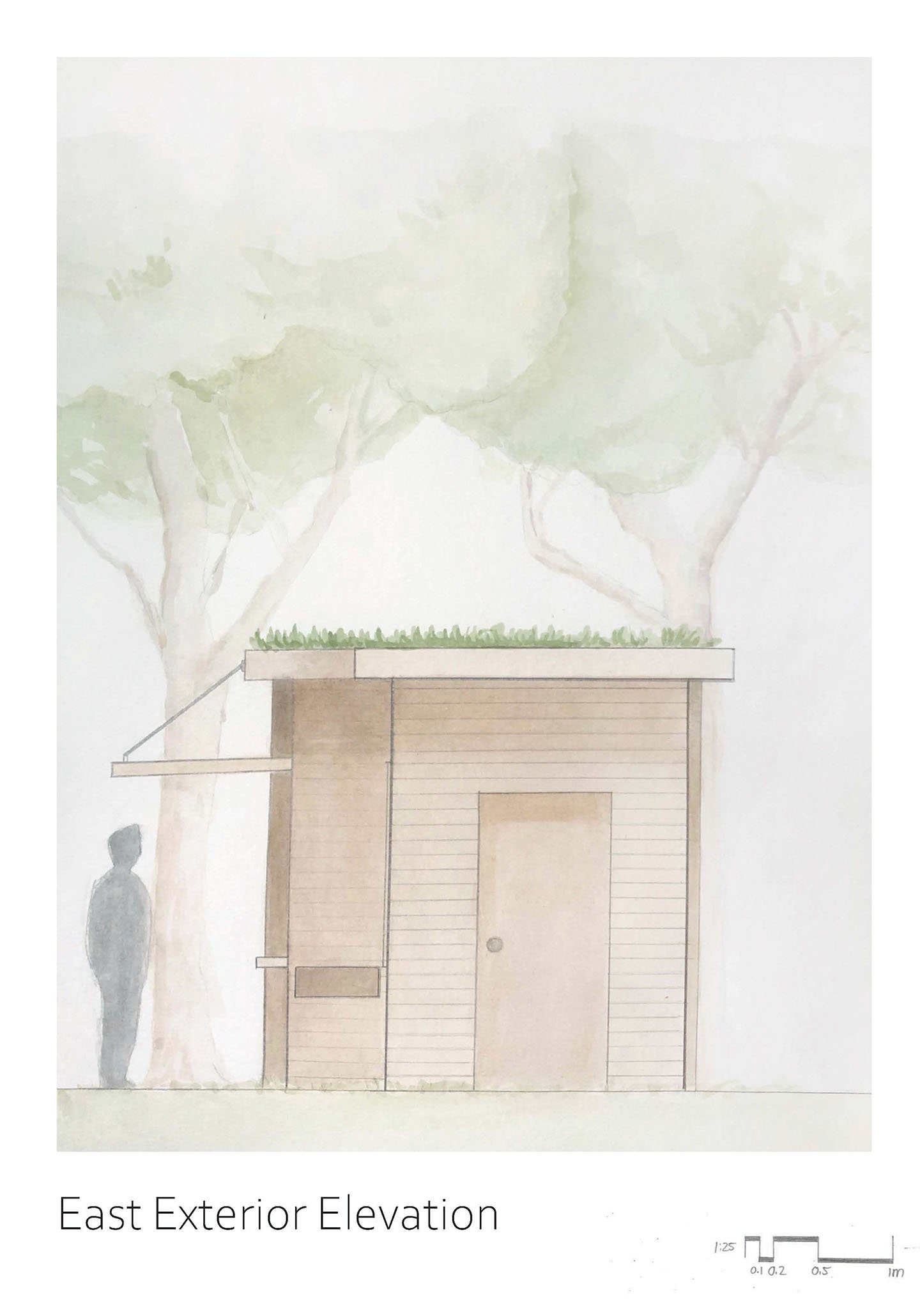

Monica Zheng

Building Roots Cafe

Building Roots Cafe

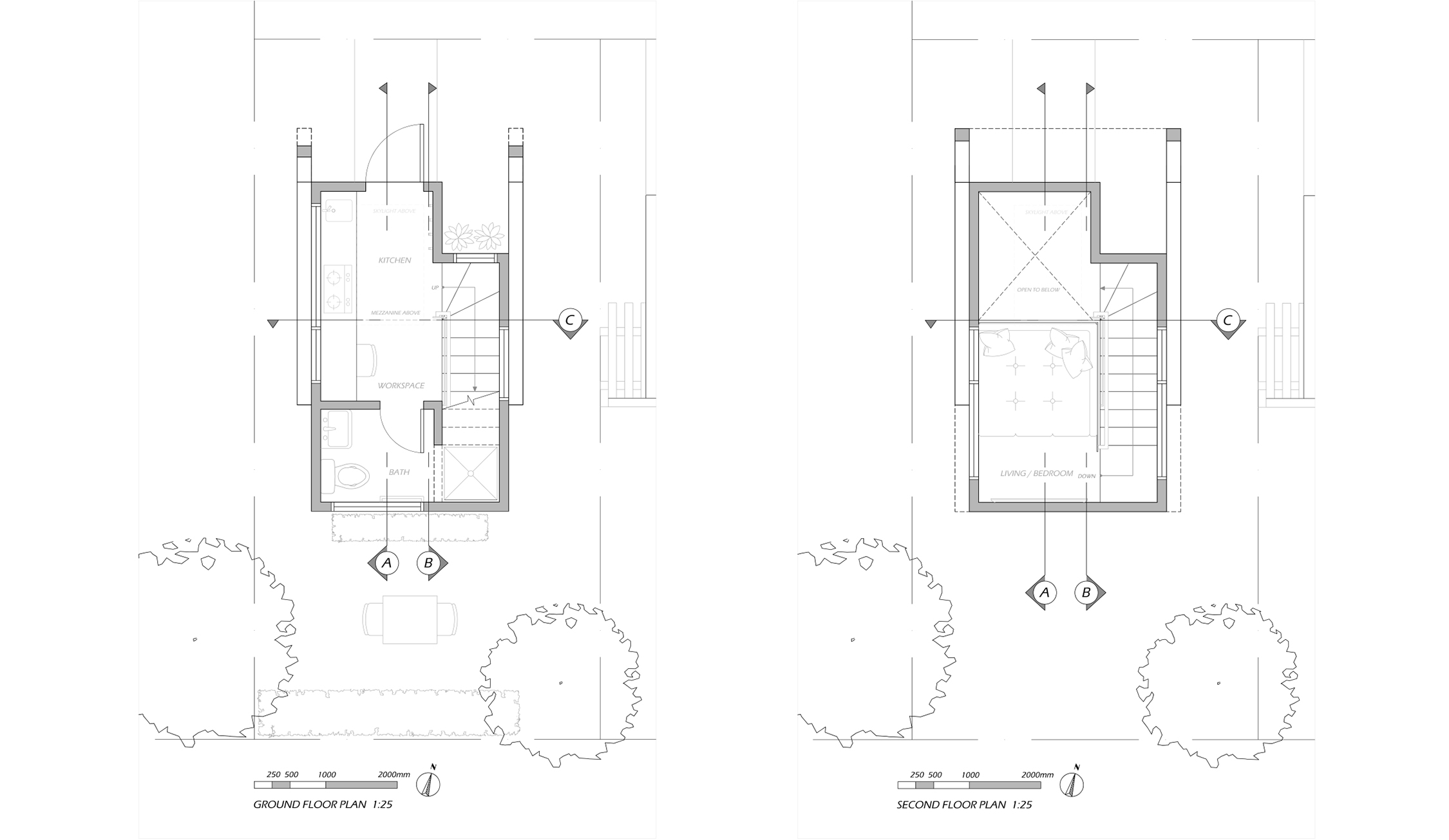

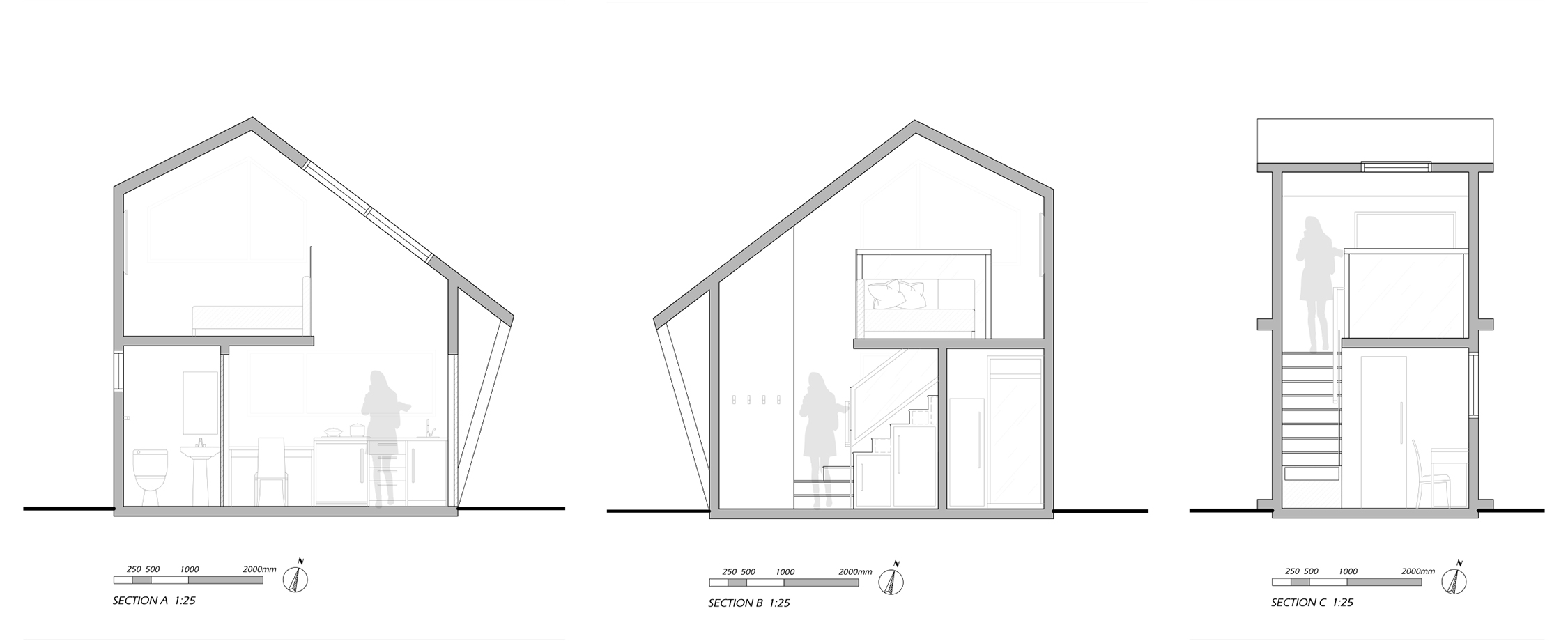

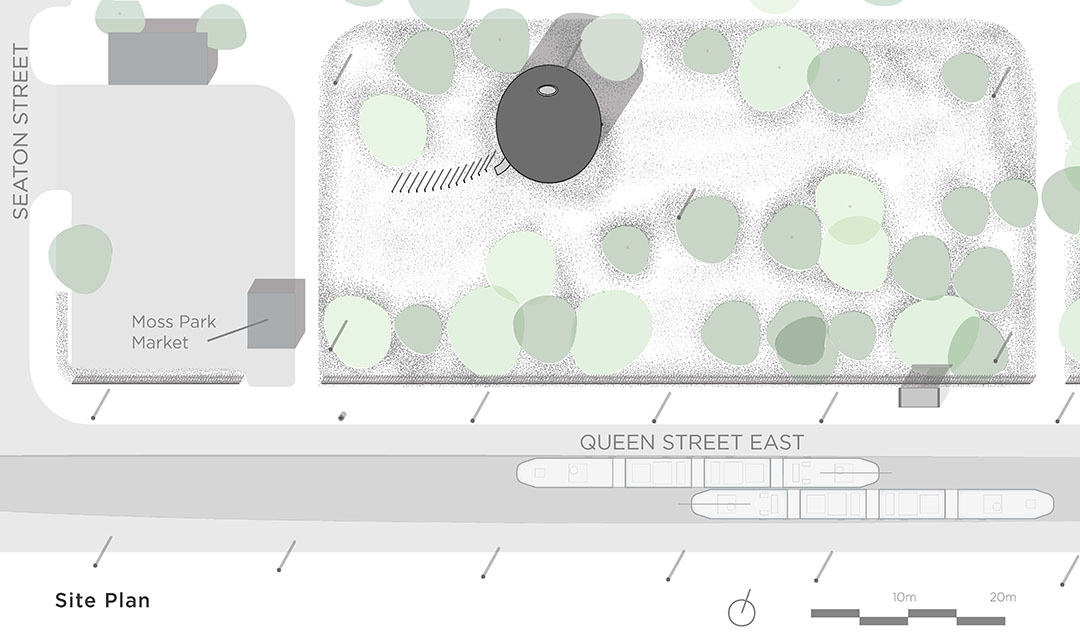

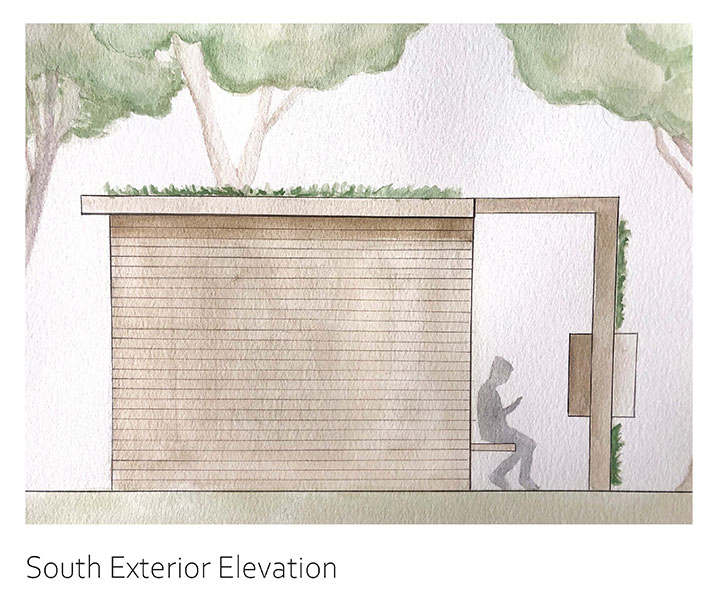

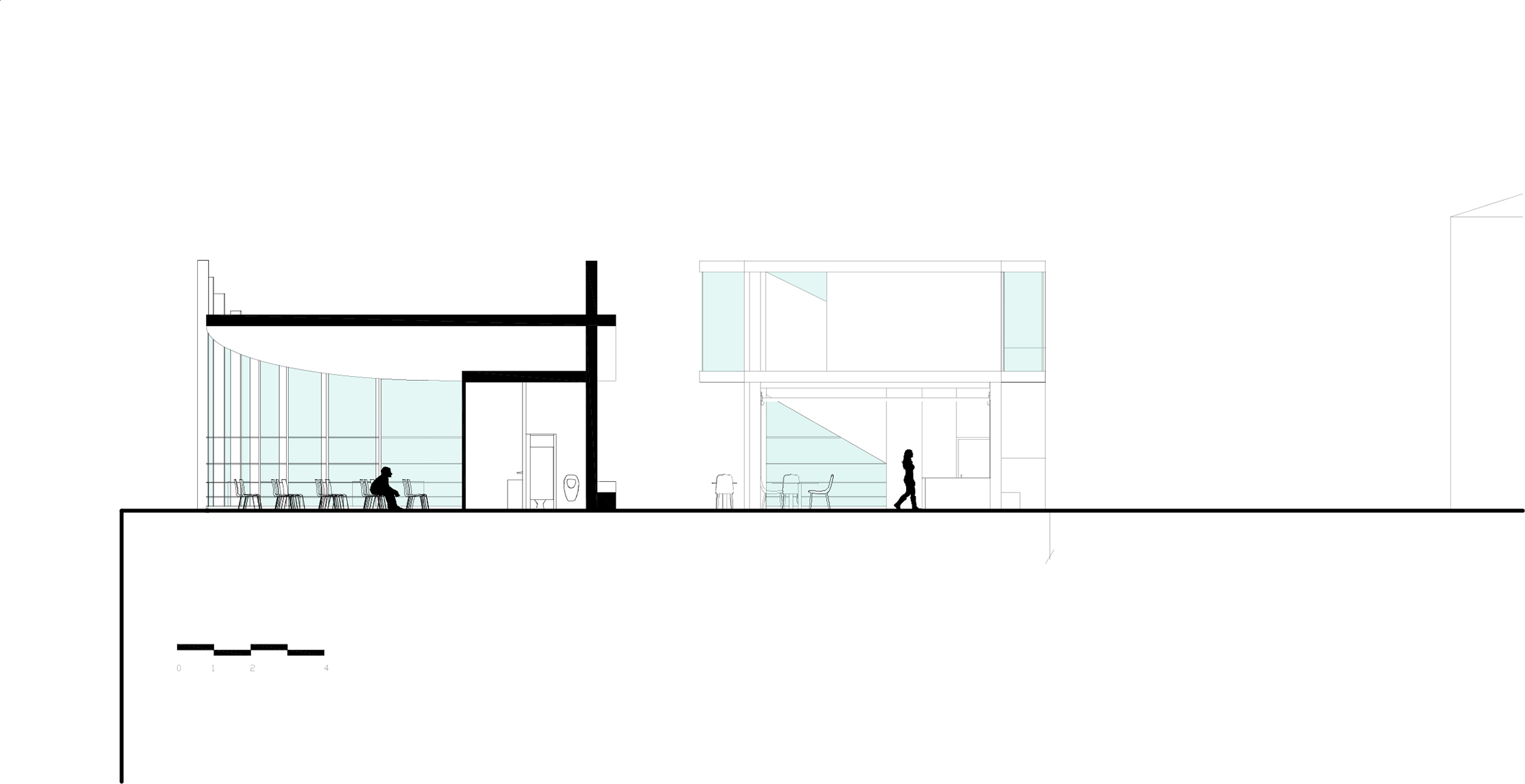

In project 2 students developed an understanding of wood construction and how to design and draw a very small structure.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

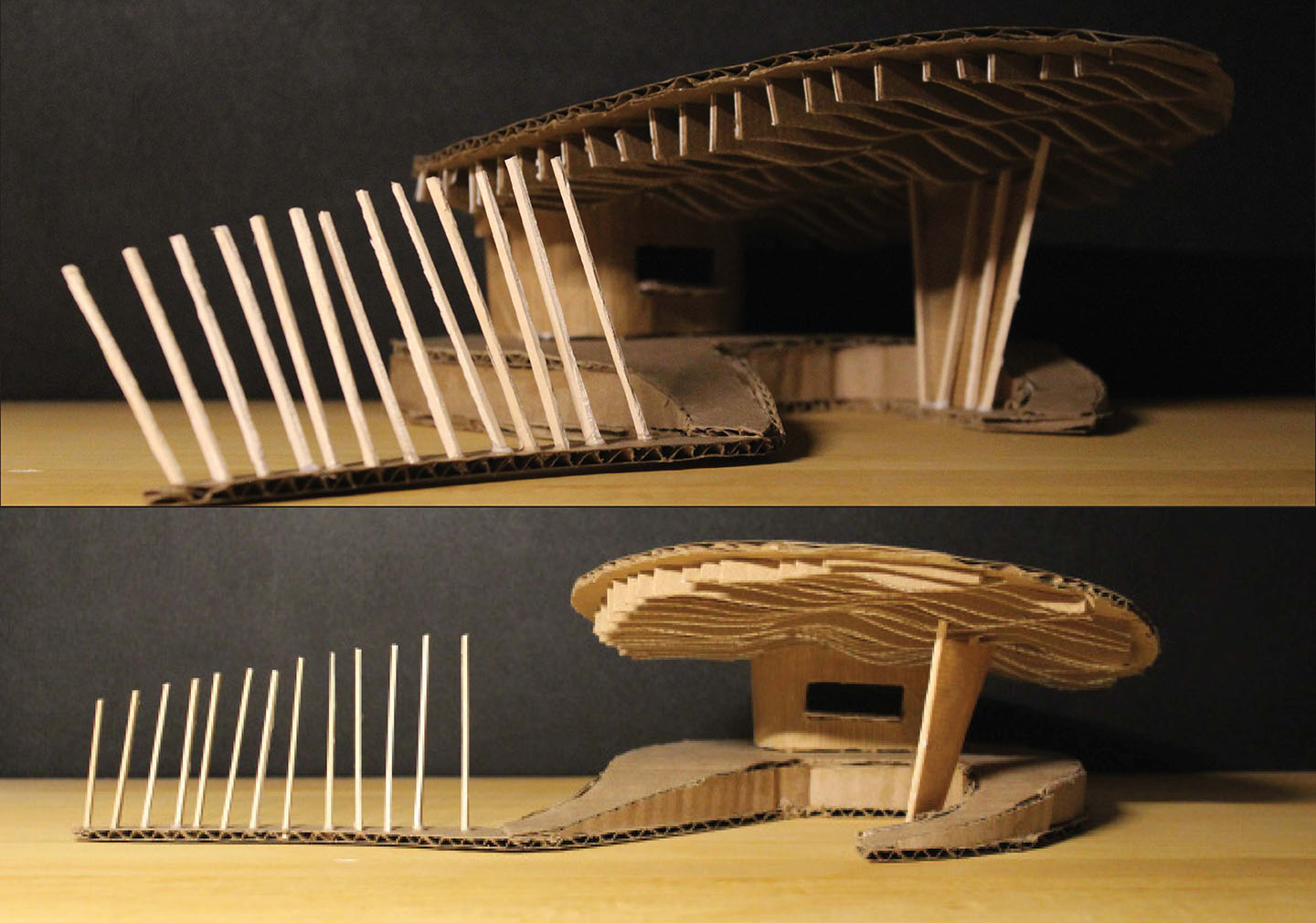

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Jana Stojanovska

Building Roots Cafe

Building Roots Cafe

In project 2 students developed an understanding of wood construction and how to design and draw a very small structure.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Todd Collis

Building Roots Cafe

Building Roots Cafe

In project 2 students developed an understanding of wood construction and how to design and draw a very small structure.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Hui Shan Cao

Building Roots Cafe

Building Roots Cafe

In project 2 students developed an understanding of wood construction and how to design and draw a very small structure.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

Their mission: To design a small serving building for an outdoor café for the Building Roots food hub at Moss Park, Toronto. (see https://buildingroots.ca/) The building will serve customers through a window/counter and have a small workspace inside. It needs to have a fun, community-building presence in the Building Roots spirit.

Building Roots is a non-profit that runs community gardens and a CSA (community supported agriculture - bags or boxes of food directly from farmers and chefs, usually picked up weekly). They have recently expanded their existing program for accessible, affordable CSA food pickup. During the pandemic they saw the need to feed more people, create a sense of community, and bring joy through music and other entertainment at their site in Toronto’s Moss Park neighbourhood. The café is meant to aid in this endeavor, using food and entertainment to help a community through trying times.

Through a series of sketches and study models you are to create a space that is appropriately scaled for Moss Park.

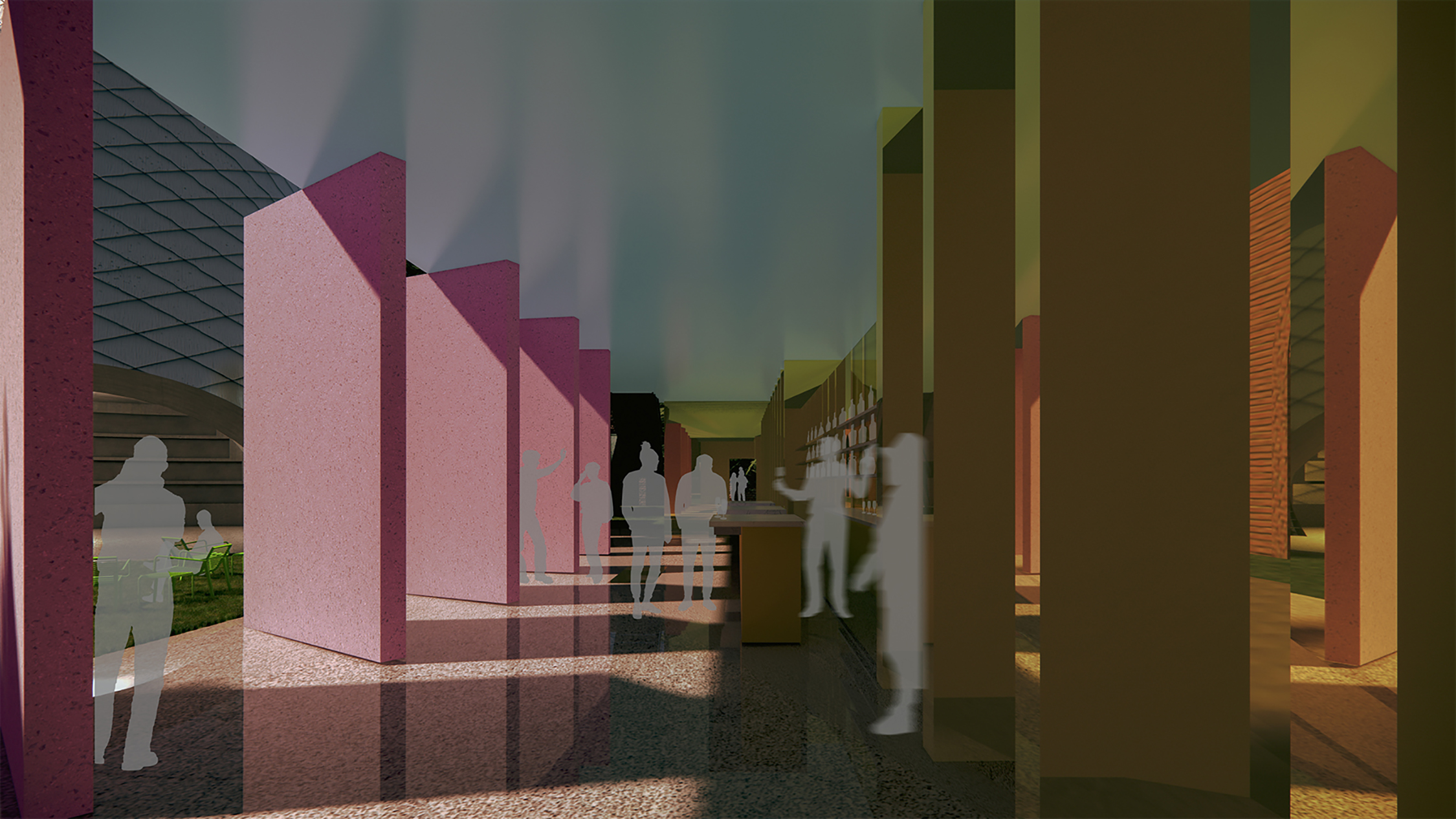

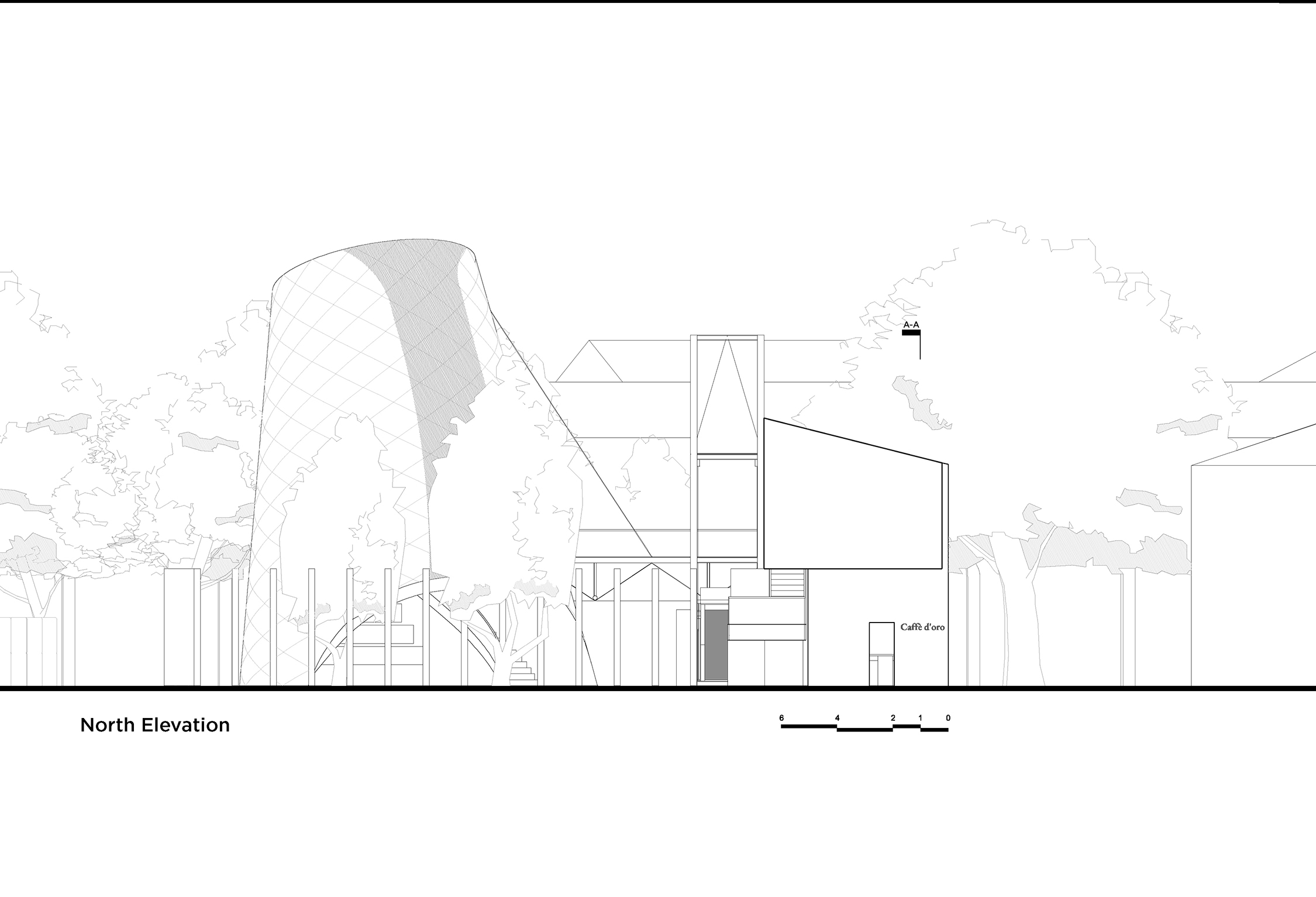

The Venice Storytelling Centre

Located at the Giardino delle Vergini, the Venice Storytelling Centre introduces a space that allows an alternative way to experience a story, attempting to expand what a story may be.

With pathways on the West, North, and East sides of the site, the project encourages the idea of arrival. Vertical revolving fins along all sides of the open courtyard creates the relationship between physical interaction and interior space. As pedestrians walk along the North path, they are provided with a peripheral glimpse of an informal story being told within the courtyard, sparking an interest to investigate further. An intended relationship between the adjacent Biennale pavilions and the site is constructed by matching the roof slope and eaves height of the new office mass sheltering the cafe. While their relationship is strong, their differences are clearly defined.

With pathways on the West, North, and East sides of the site, the project encourages the idea of arrival. Vertical revolving fins along all sides of the open courtyard creates the relationship between physical interaction and interior space. As pedestrians walk along the North path, they are provided with a peripheral glimpse of an informal story being told within the courtyard, sparking an interest to investigate further. An intended relationship between the adjacent Biennale pavilions and the site is constructed by matching the roof slope and eaves height of the new office mass sheltering the cafe. While their relationship is strong, their differences are clearly defined.

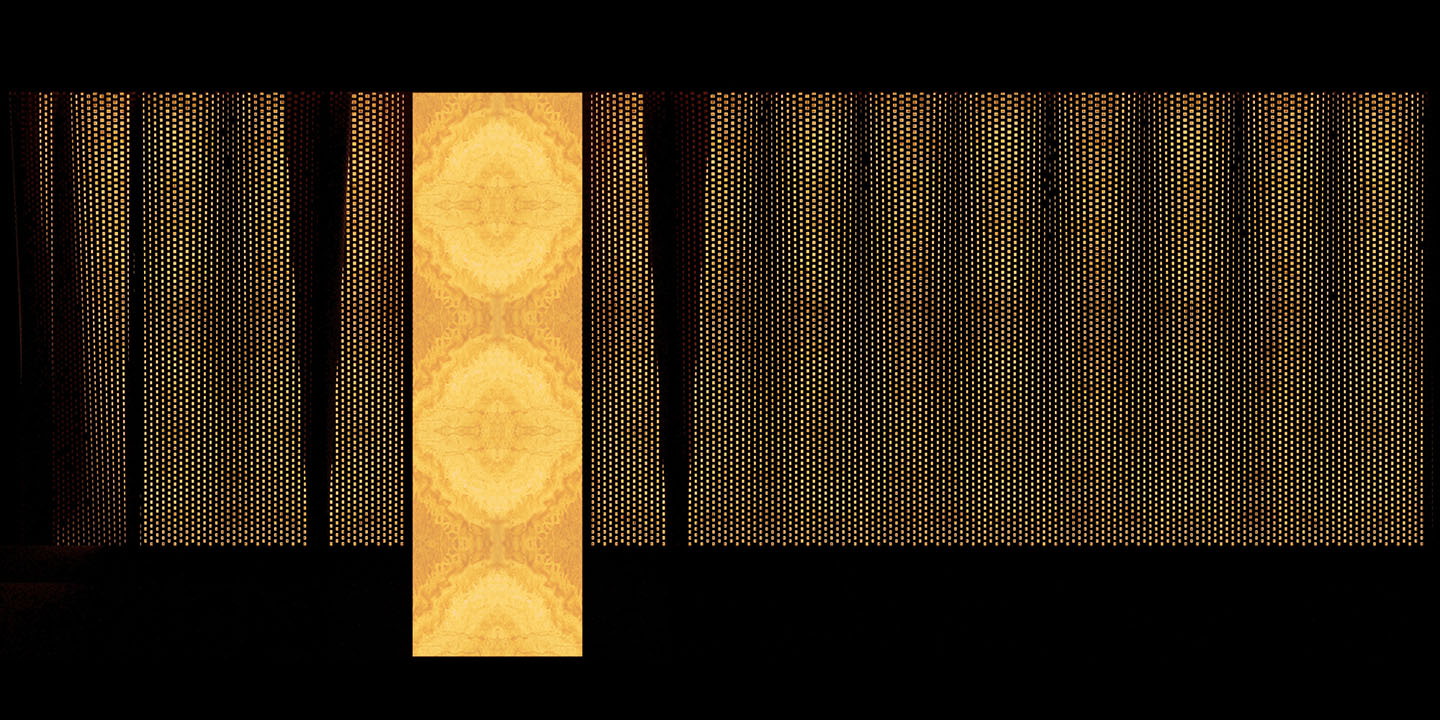

The revolving bright pink fins define the interior courtyard space, while the golden fins along the West define Caffé d’Oro, the Golden Coffee. The two elements work in unison, defining the loggia. The sky-blue office mass creates the relationship to the bright blue sky, golden fins connect with the city’s Byzantine heritage, and vibrant colours model admiration for the beautiful colours used in Venetian blown glass and glass mosaics. The vibrant colours surrounding the storytelling space over-stimulate the senses - senses which are then under-stimulated when attention is turned to the storytelling space, emphasizing the story itself.

Upon entry to the storytelling space, one’s senses begin to calm through the muted gray exterior then interior space. Light only from the slight void in the roof and the dim glow from the punched holes through the wall connect one with a greater sense of the infinite. As one lays down on the mesh, they are suspended, leaving them motionless as the story progresses. The listeners are fully immersed in the story being told - no matter the tone, the importance is held on the voice and the story itself. The storytelling space is its own story yet suits any tale being told. Whether the story is being told nearby or disconnected through the sound of an echo, the storyteller controls the emotion of the occupants, no matter their proximity.

Upon entry to the storytelling space, one’s senses begin to calm through the muted gray exterior then interior space. Light only from the slight void in the roof and the dim glow from the punched holes through the wall connect one with a greater sense of the infinite. As one lays down on the mesh, they are suspended, leaving them motionless as the story progresses. The listeners are fully immersed in the story being told - no matter the tone, the importance is held on the voice and the story itself. The storytelling space is its own story yet suits any tale being told. Whether the story is being told nearby or disconnected through the sound of an echo, the storyteller controls the emotion of the occupants, no matter their proximity.

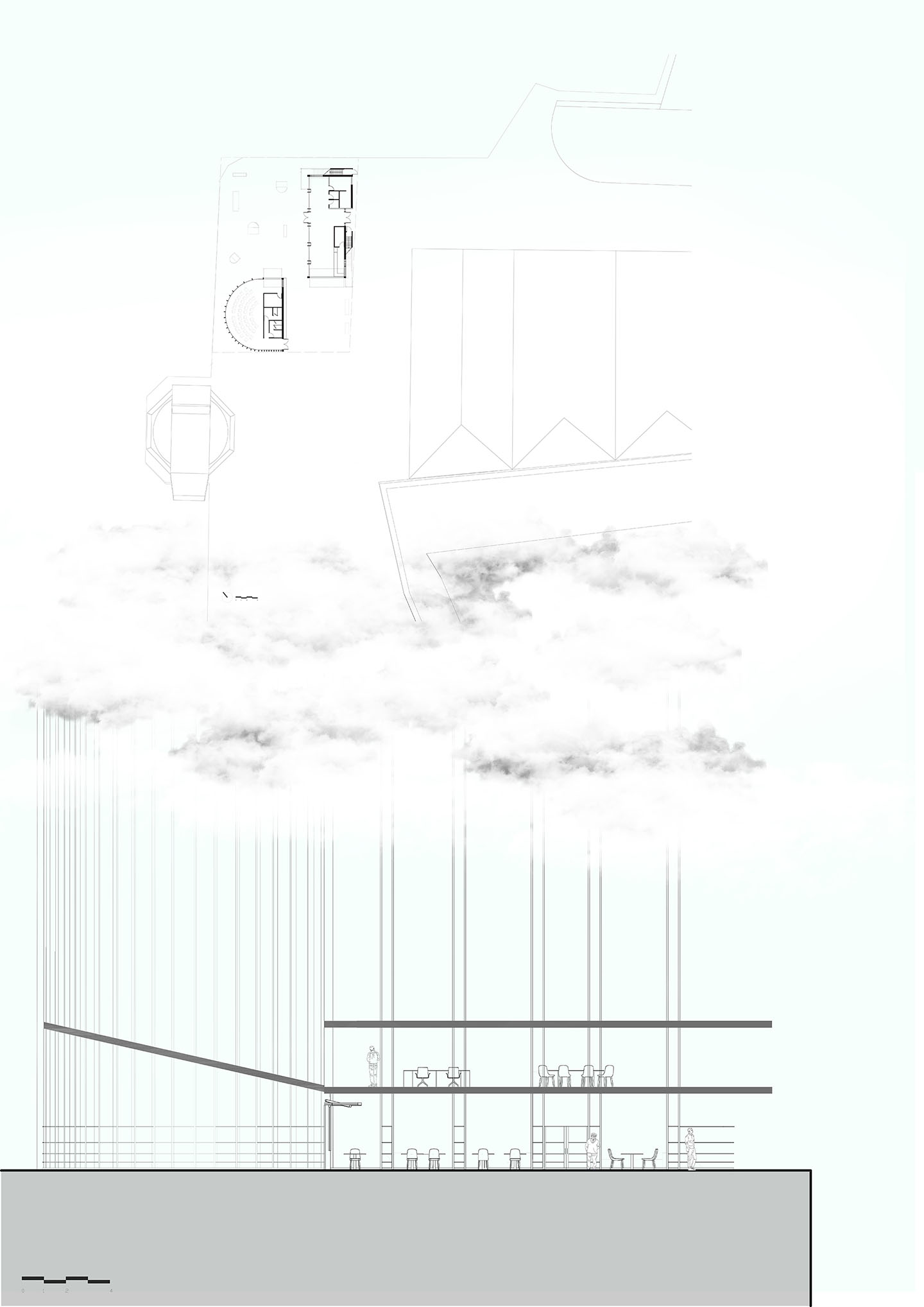

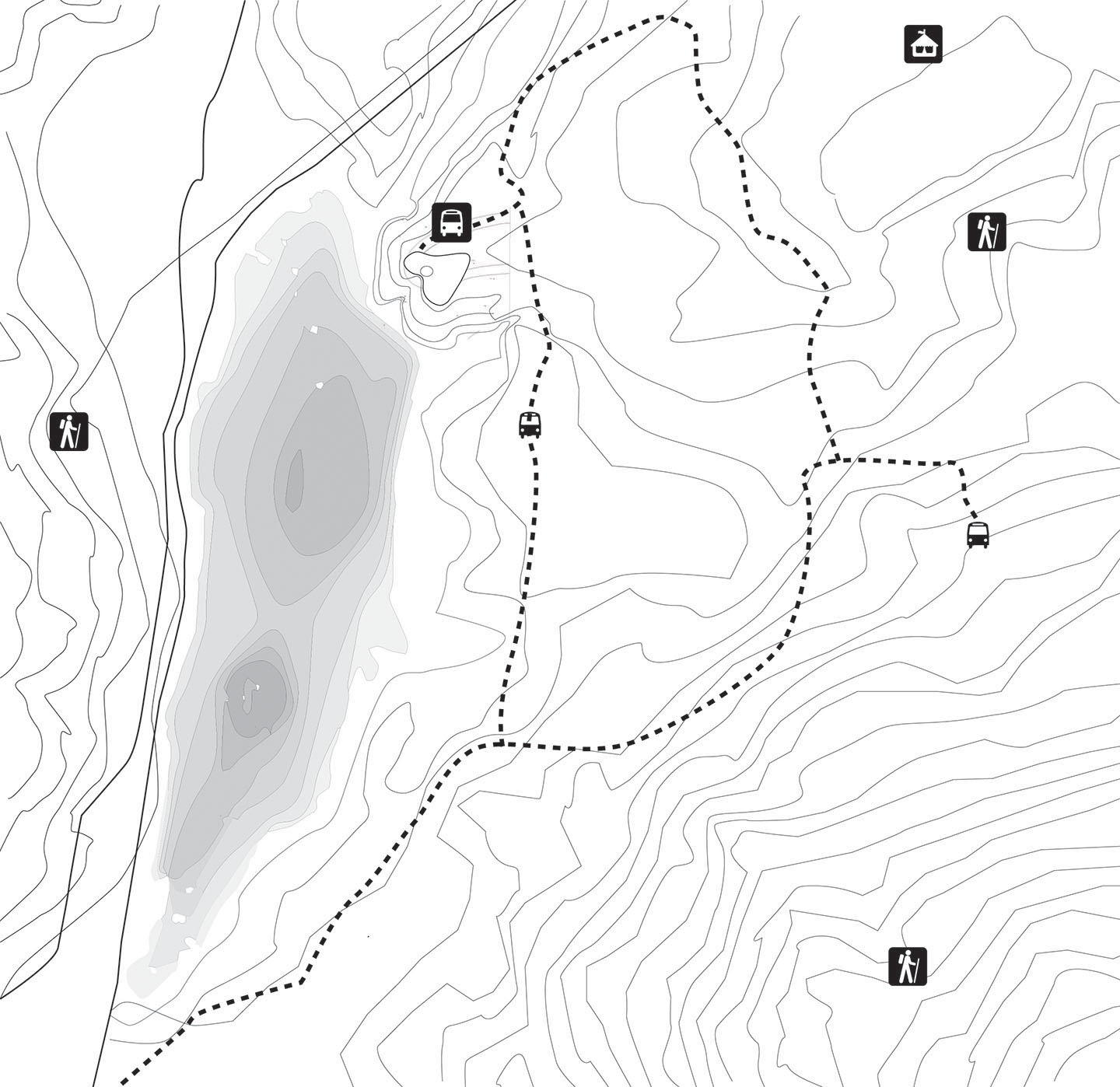

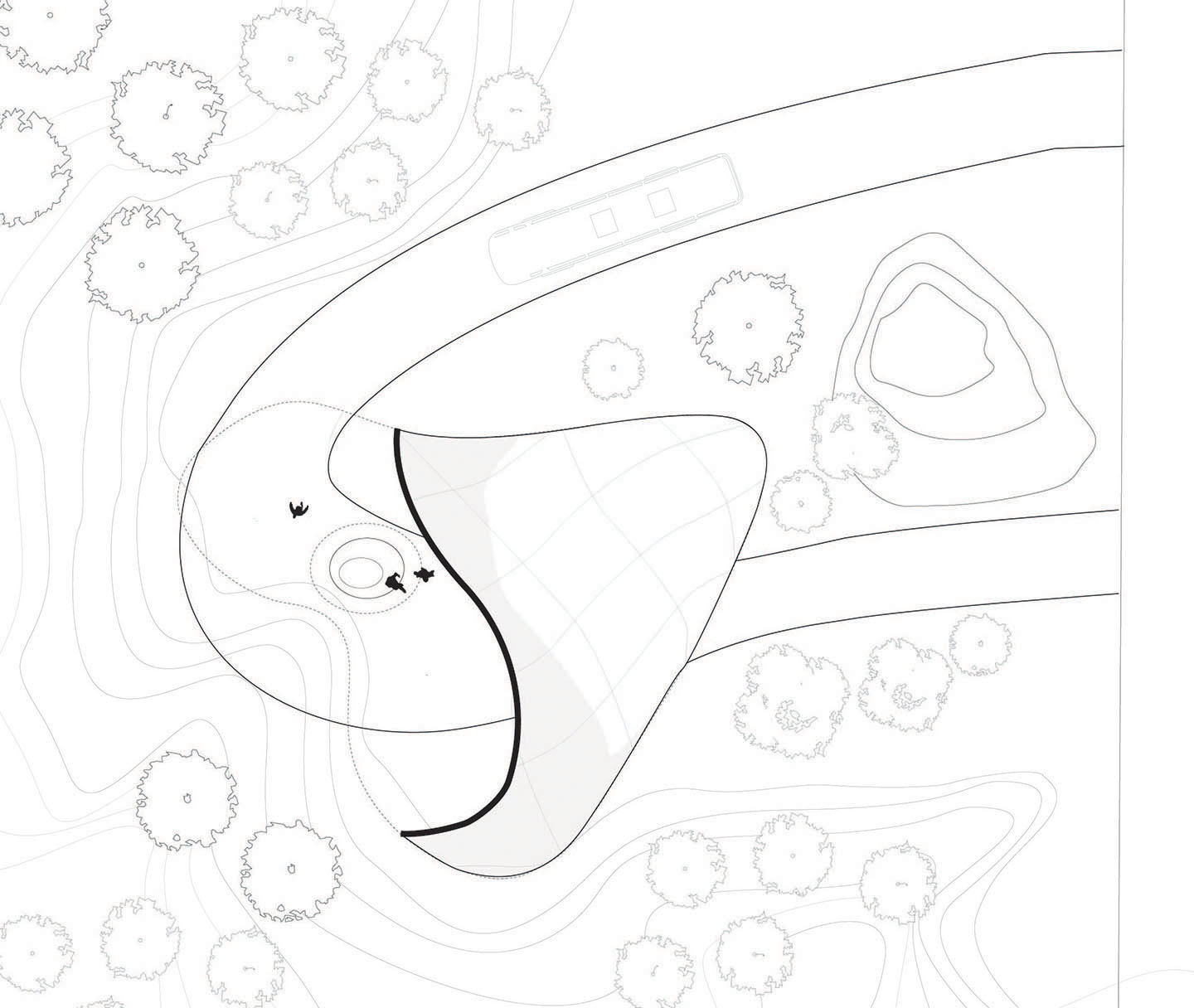

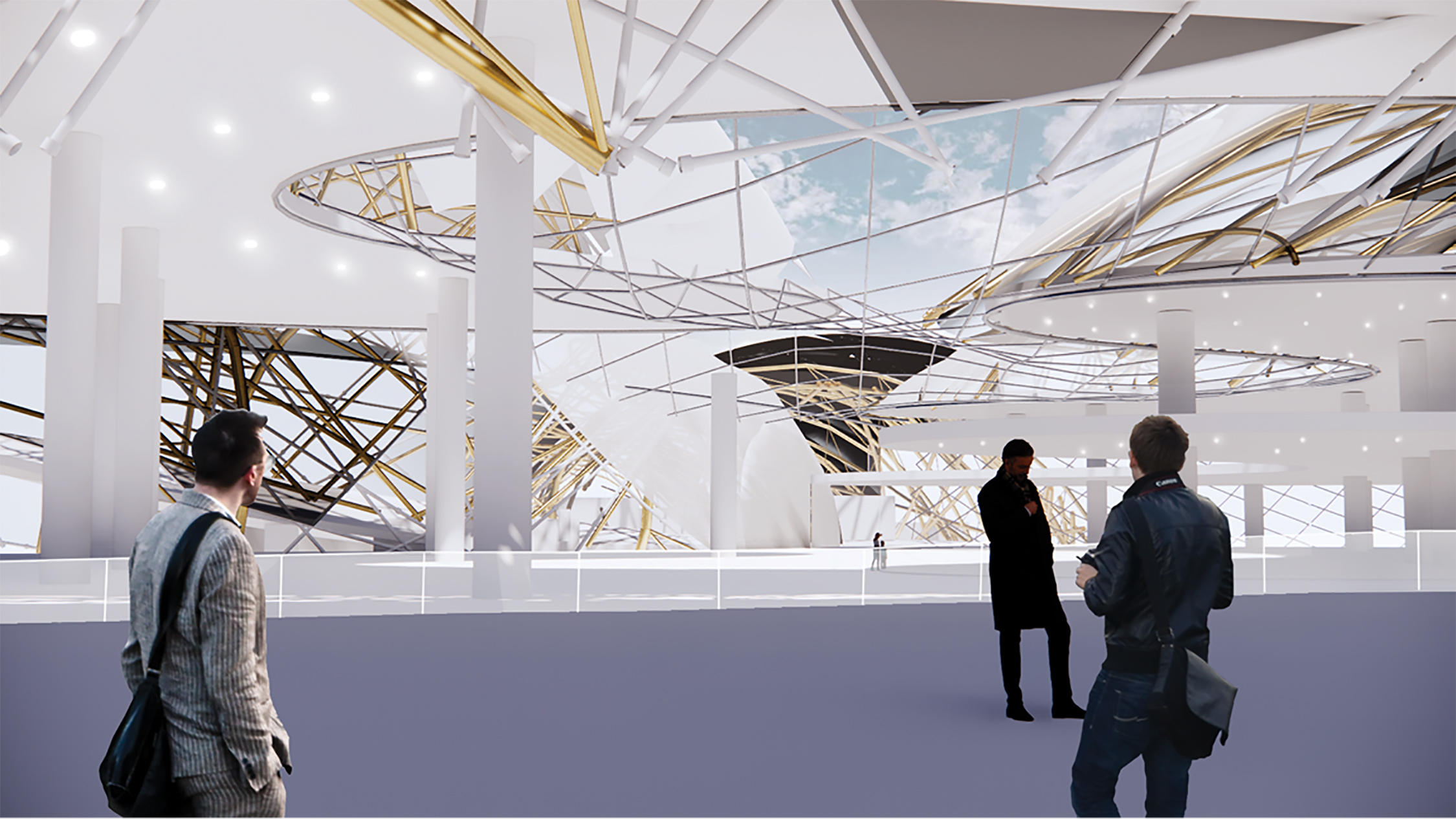

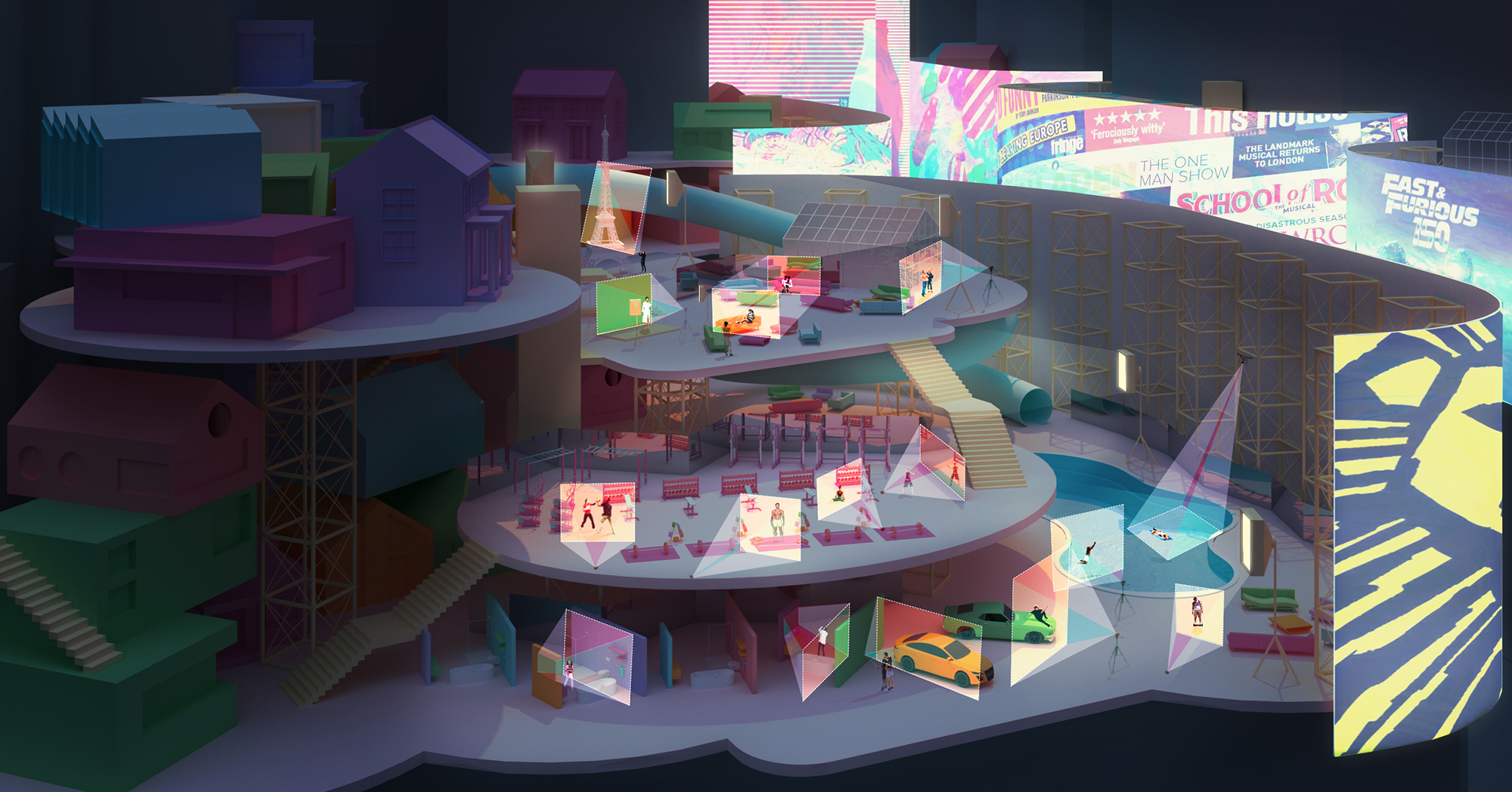

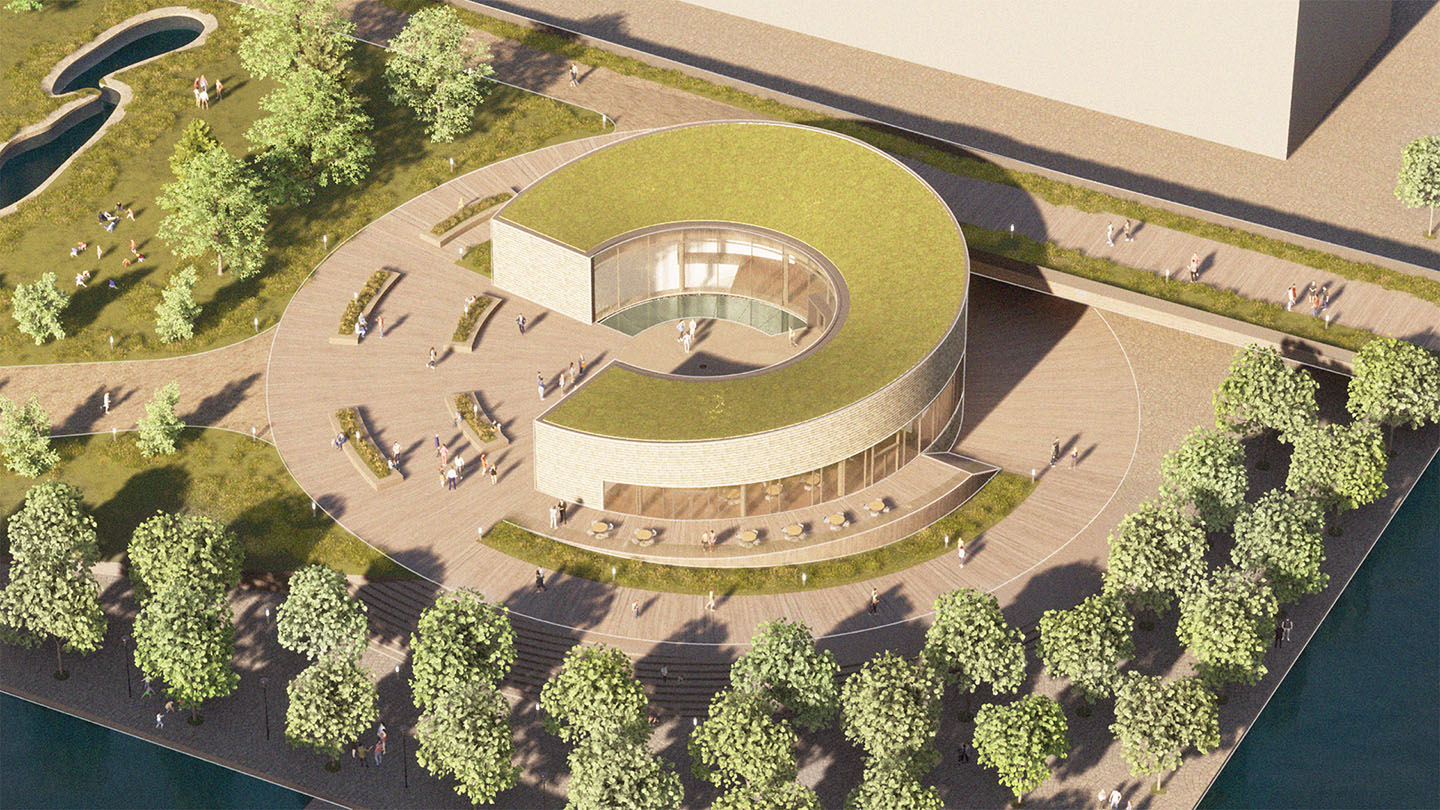

Building Stories

The primary goal of this project is to capture the essence of storytelling by allowing the visitors to connect and share. Our stories pass on from person to person, spreading out much like how water ripples and flows. The movement of water is the inspiration for creating a space that encourages sharing of these stories.

Building Stories

Project Description:

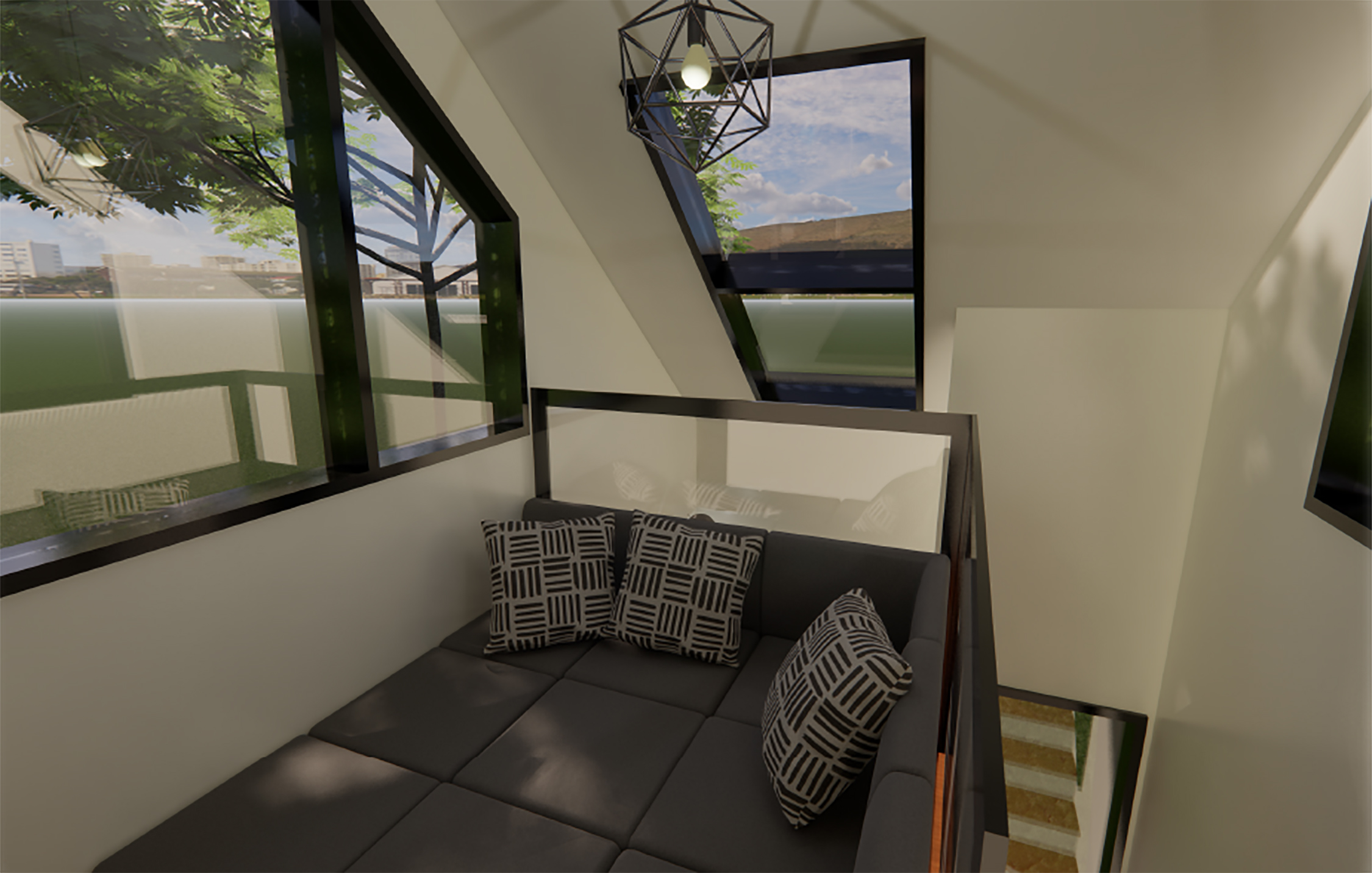

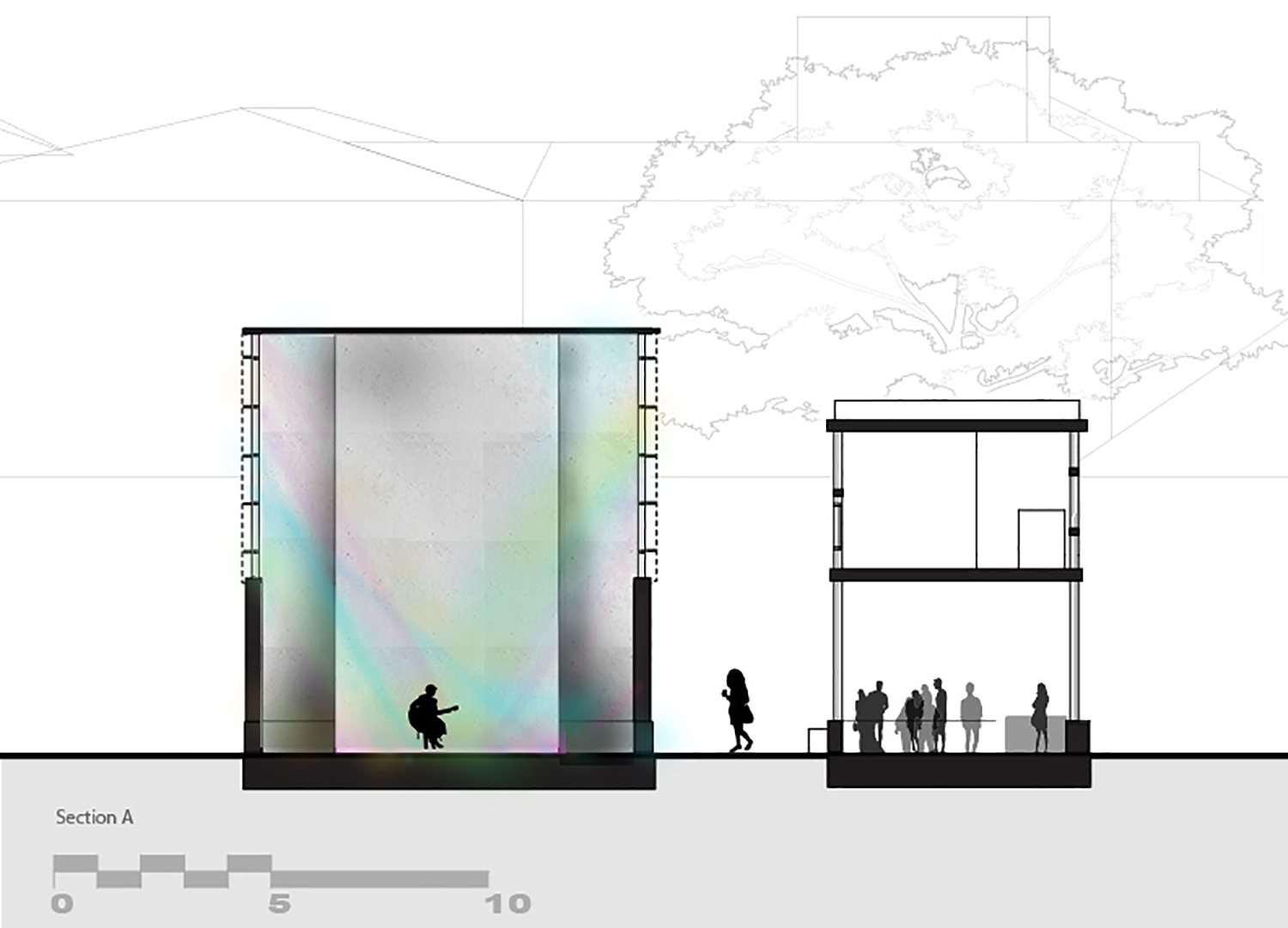

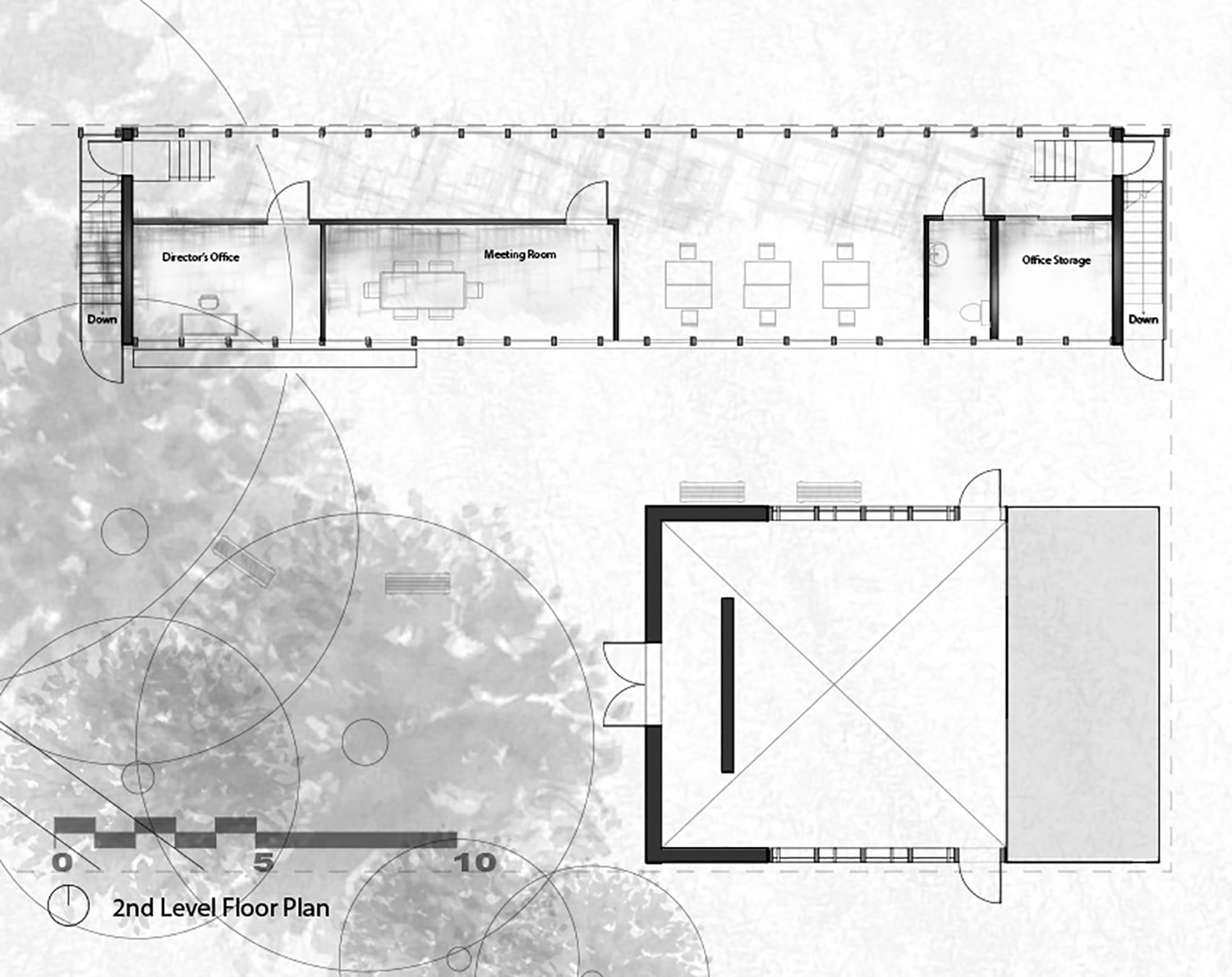

Storytelling can be a dreamlike experience that reveals new things about the world and puts the vastness of the universe in perspective. This Storytelling Biennale pavilion reaches up into the sky and opens up to the corner of the site. The smaller of the two public spaces acts as the threshold with views deep into the café, places to relax and a narrow transitional opening into the vast storytelling space while the second brings people together at the edge of a beautiful view. Unifying the three program areas are the elongated café bookshelves that act as both window frame and mullion, stretching endlessly into the clouds.

Storytelling can be a dreamlike experience that reveals new things about the world and puts the vastness of the universe in perspective. This Storytelling Biennale pavilion reaches up into the sky and opens up to the corner of the site. The smaller of the two public spaces acts as the threshold with views deep into the café, places to relax and a narrow transitional opening into the vast storytelling space while the second brings people together at the edge of a beautiful view. Unifying the three program areas are the elongated café bookshelves that act as both window frame and mullion, stretching endlessly into the clouds.

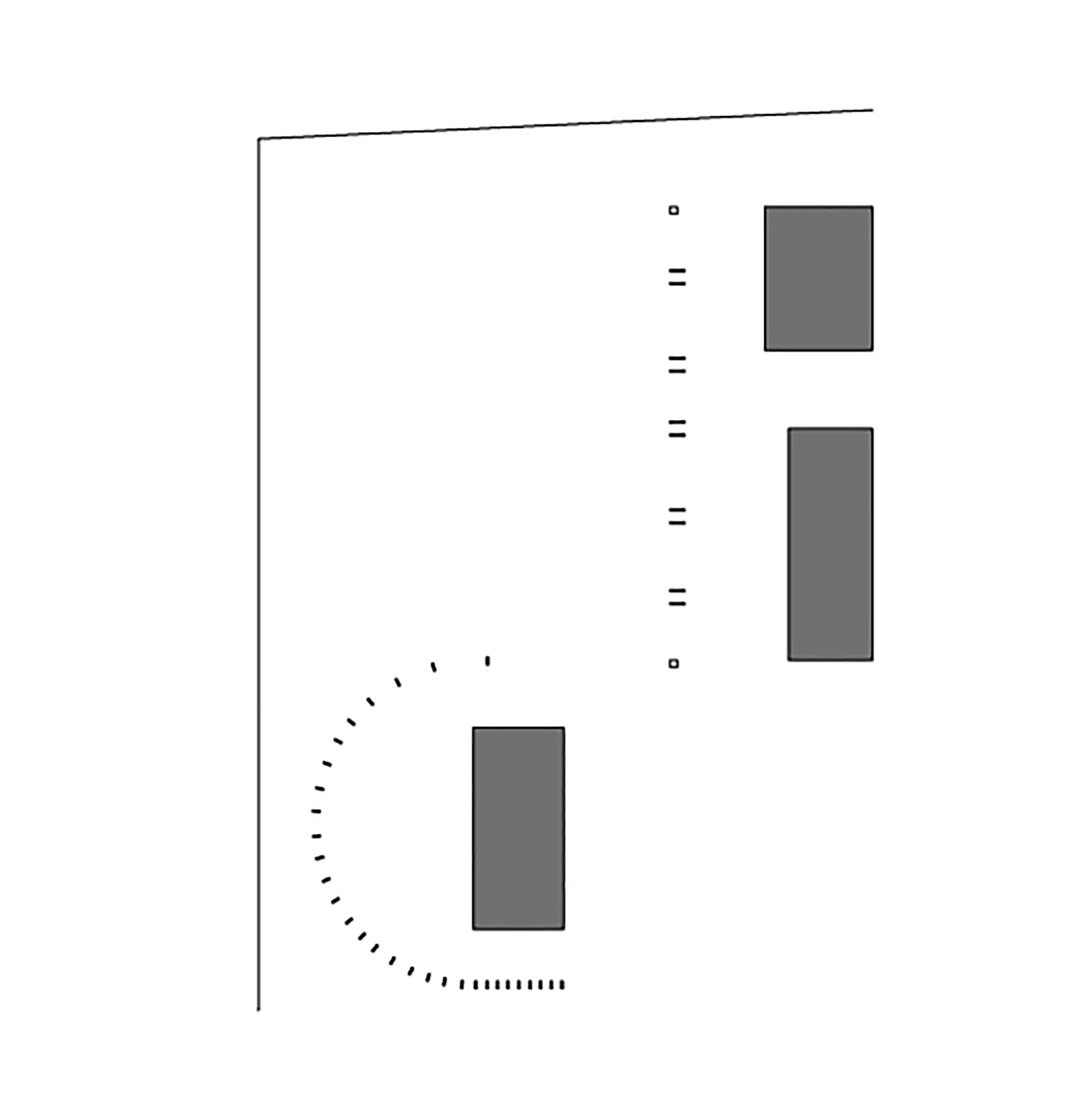

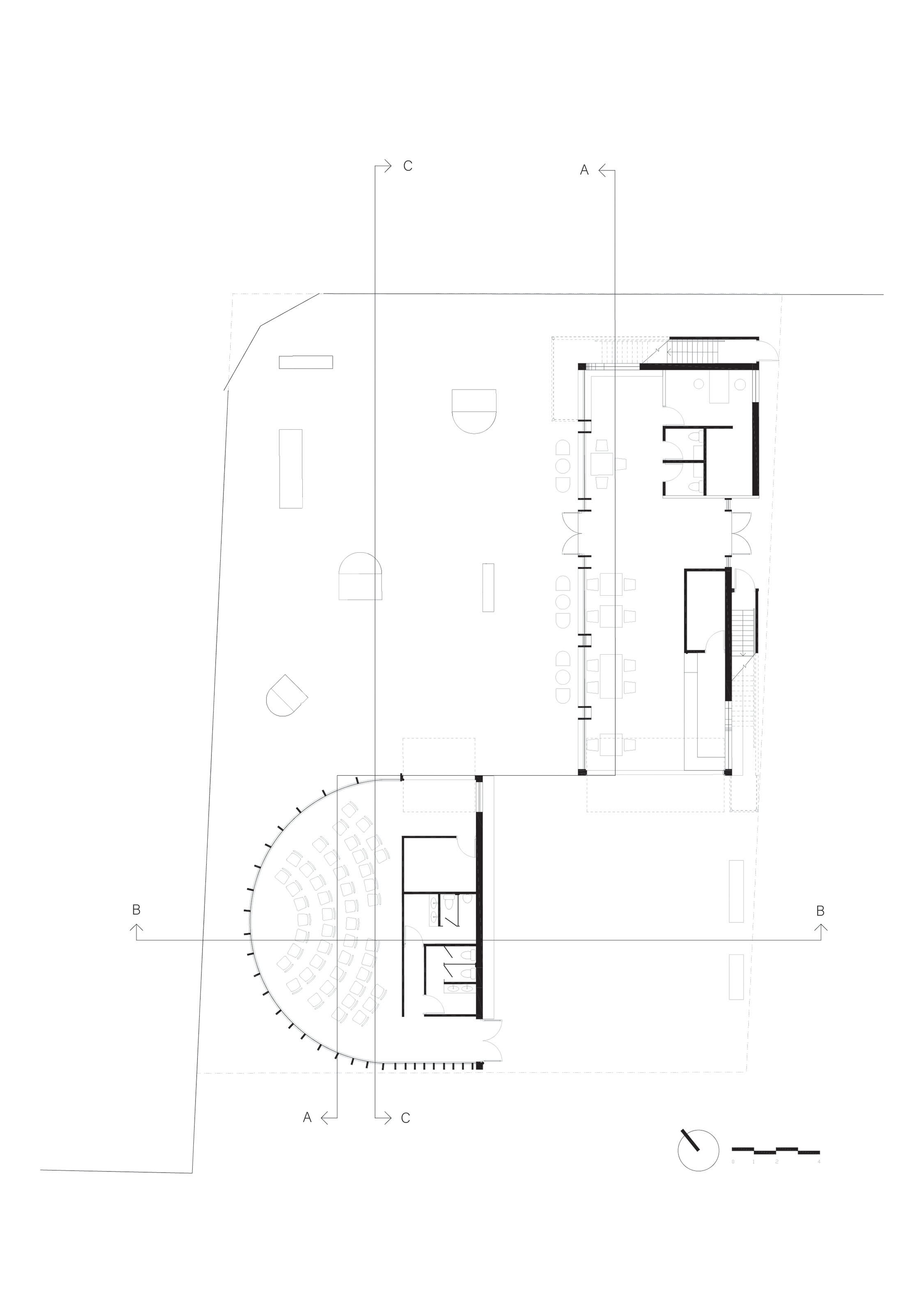

Assignment Context:

The Venice Biennale (La Biennale di Venezia) has decided to construct a new facility dedicated to storytelling on the grounds of the Arsenale in Venice. You have been commissioned to propose a design for the new building. The building will contain a café (potentially replacing one of the existing Biennale cafes), a space for storytelling gatherings that can be used for other purposes (able to hold an audience of about 50), and office space for a staff of 2 to 4 people as well as a manager.

The Venice Biennale (La Biennale di Venezia) has decided to construct a new facility dedicated to storytelling on the grounds of the Arsenale in Venice. You have been commissioned to propose a design for the new building. The building will contain a café (potentially replacing one of the existing Biennale cafes), a space for storytelling gatherings that can be used for other purposes (able to hold an audience of about 50), and office space for a staff of 2 to 4 people as well as a manager.

Hide & Seek

Building Stories is a design project for a storytelling space for the Venice Biennale. In this intimate site, different levels of opacity and materiality are used throughout the design of the buildings to bring visitors on a journey of exploring the hidden and the seen spaces.

McGall Baraceros

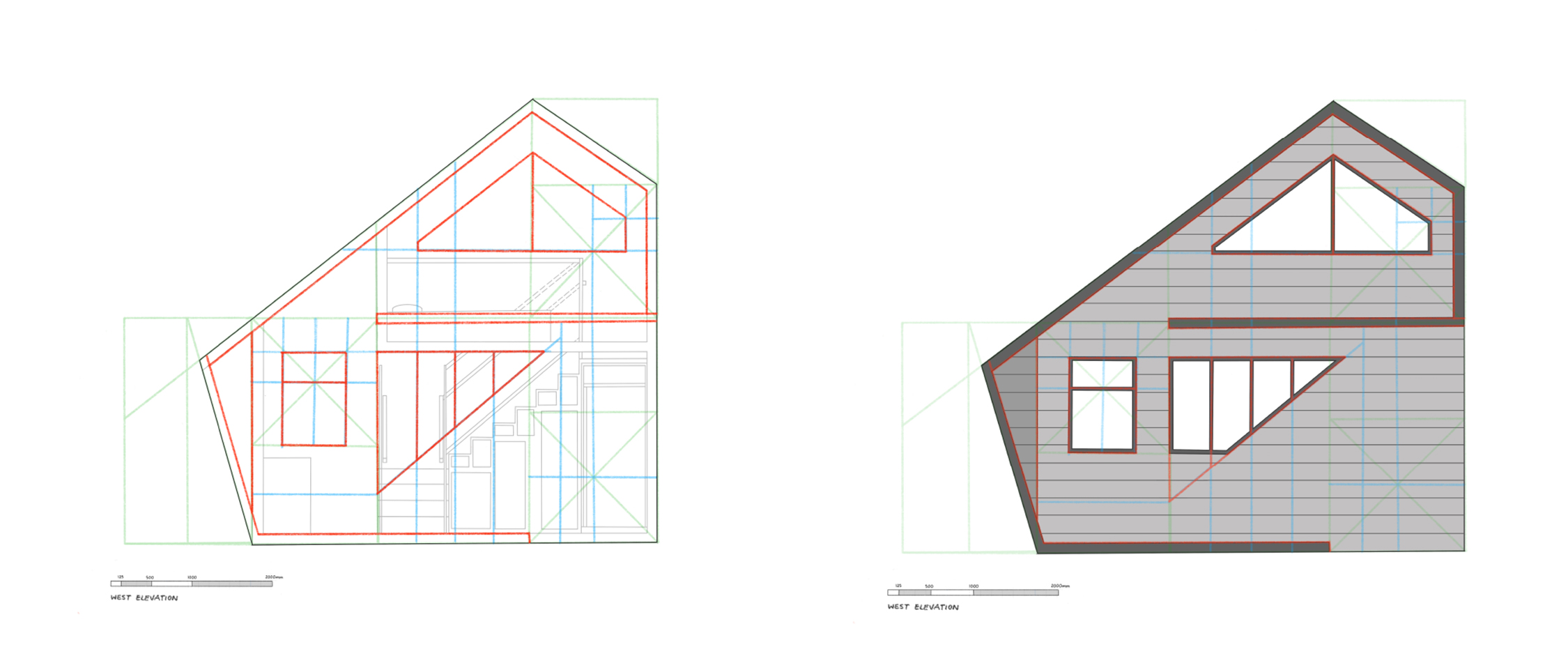

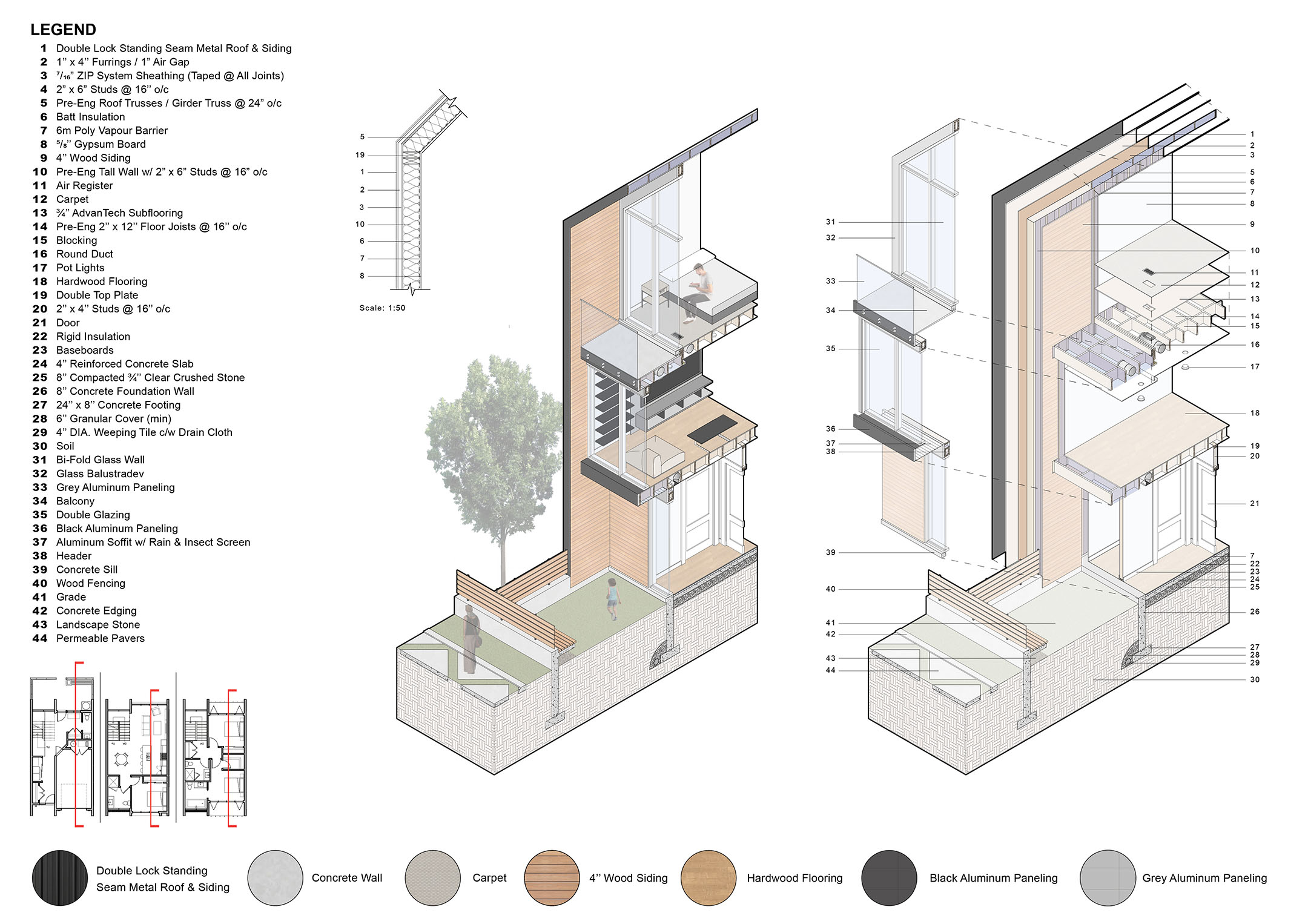

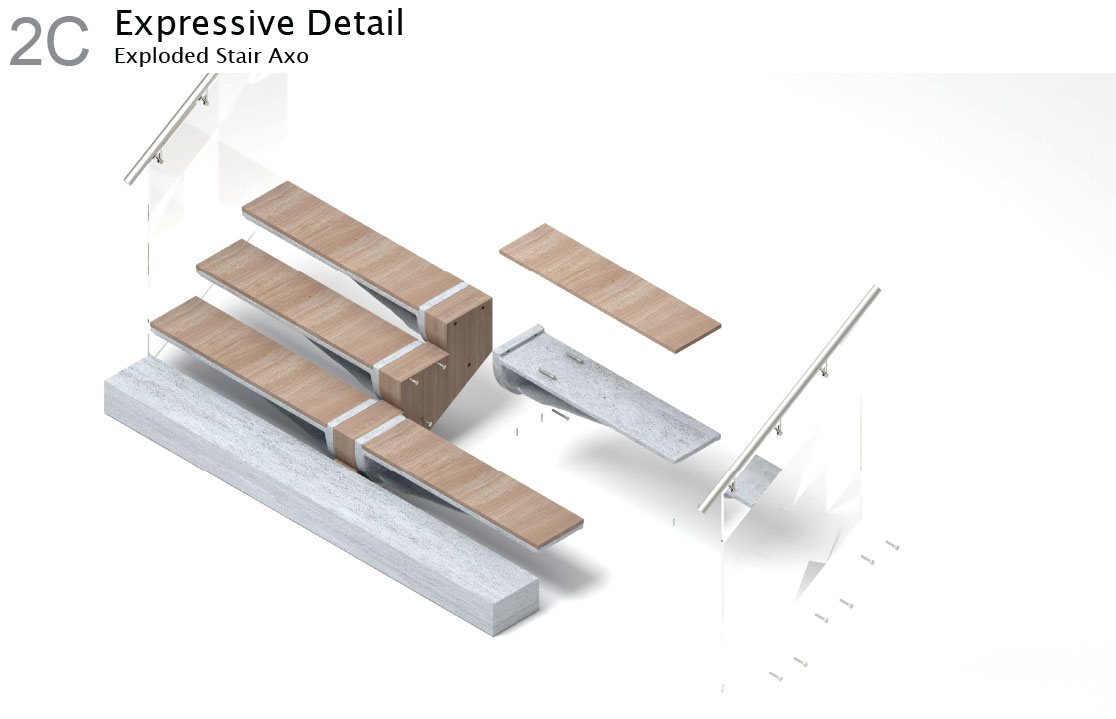

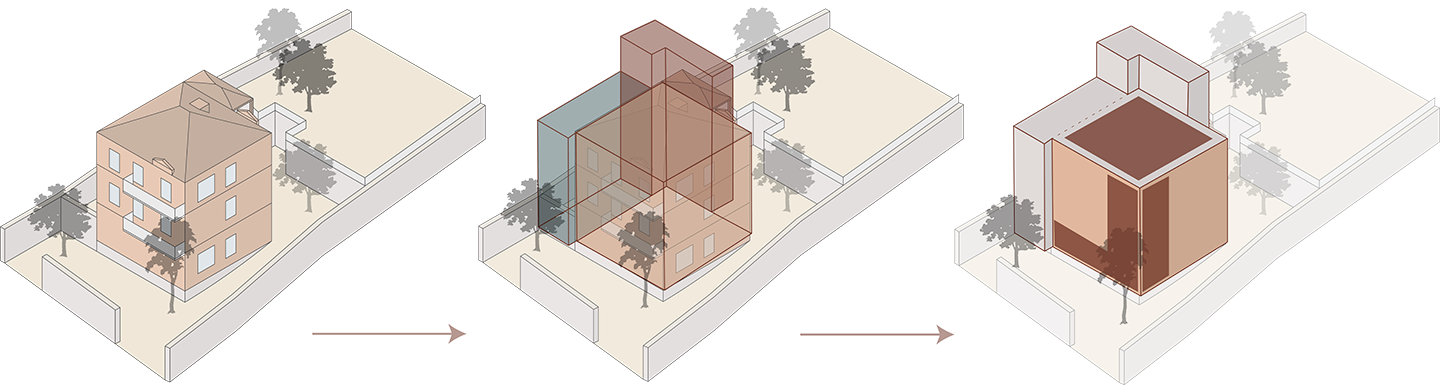

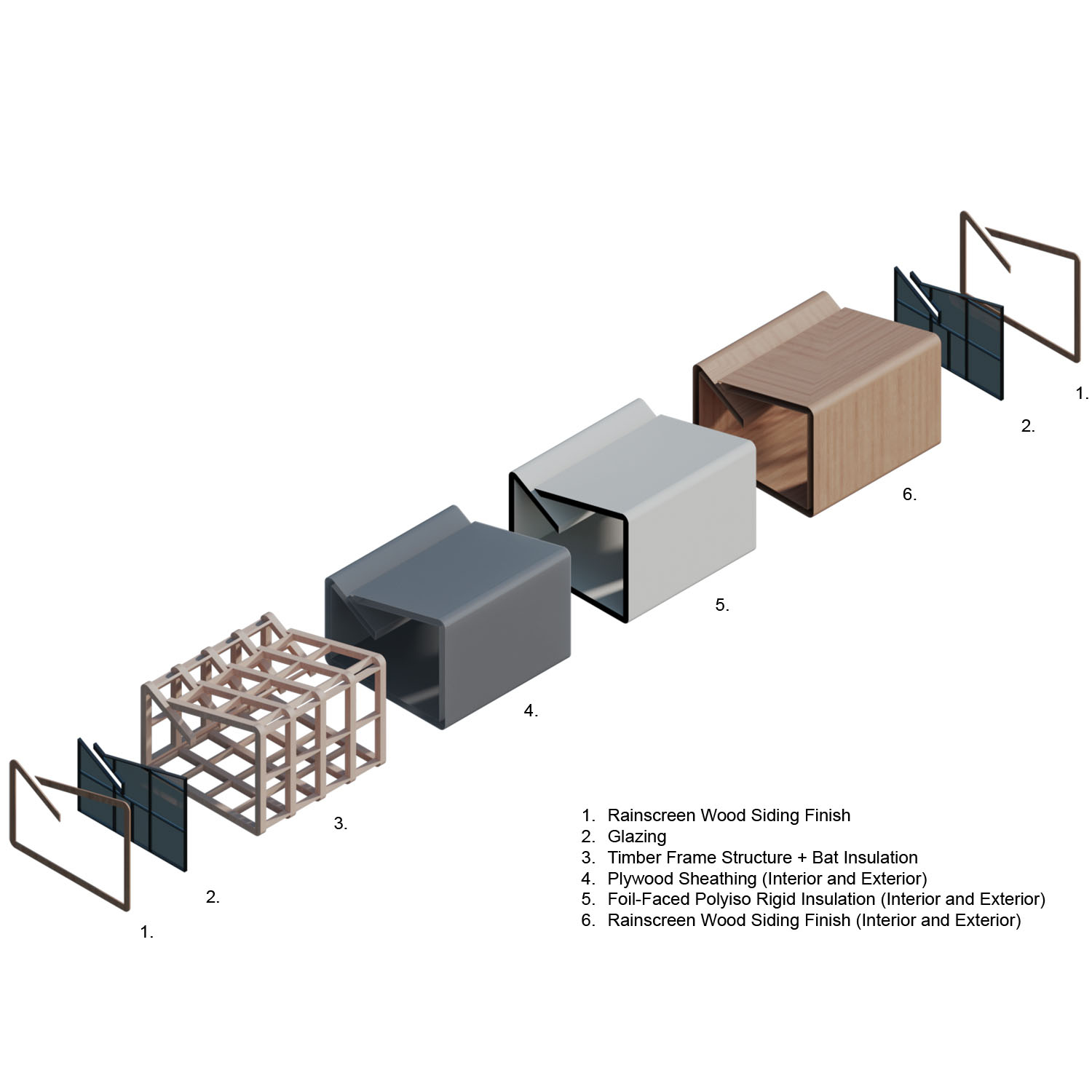

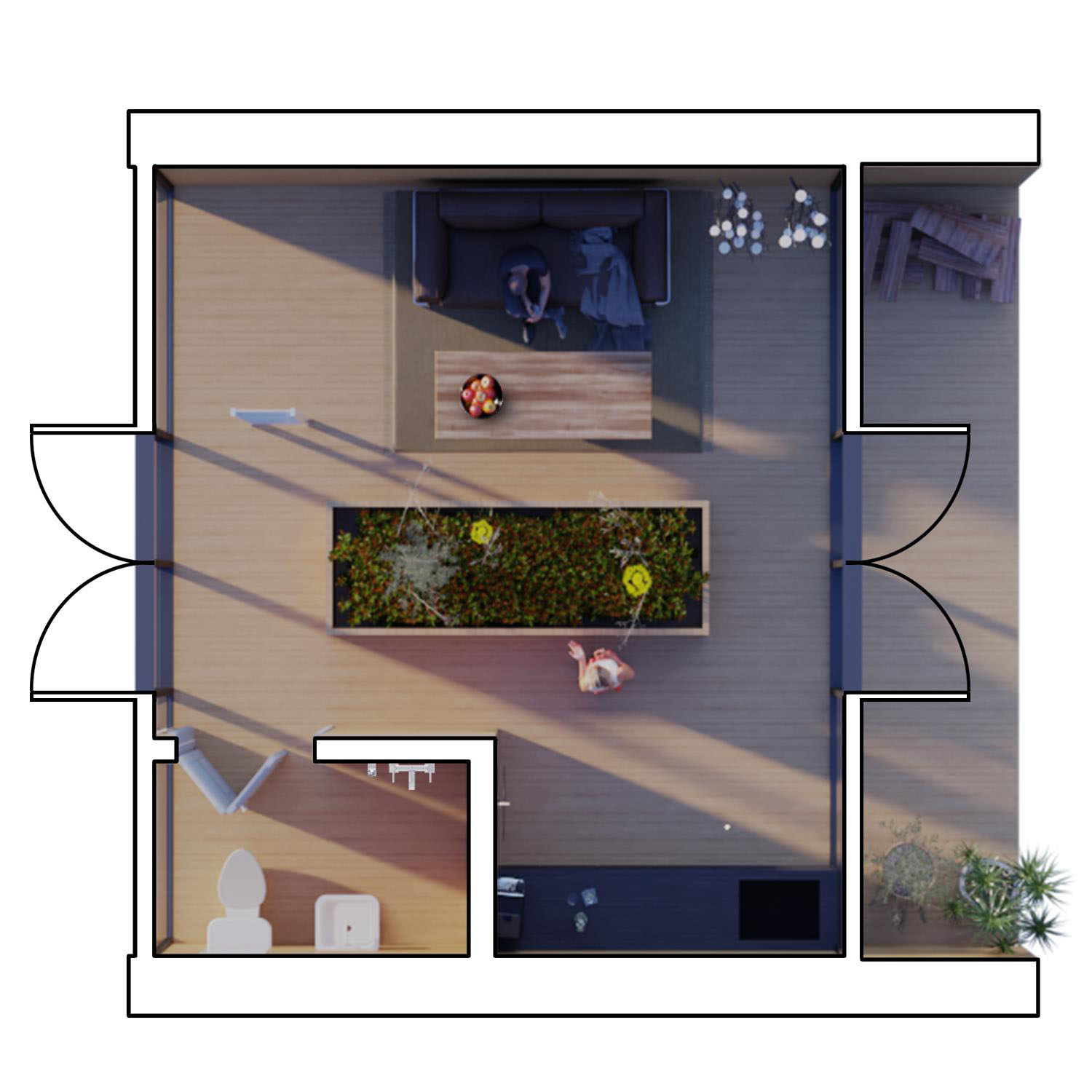

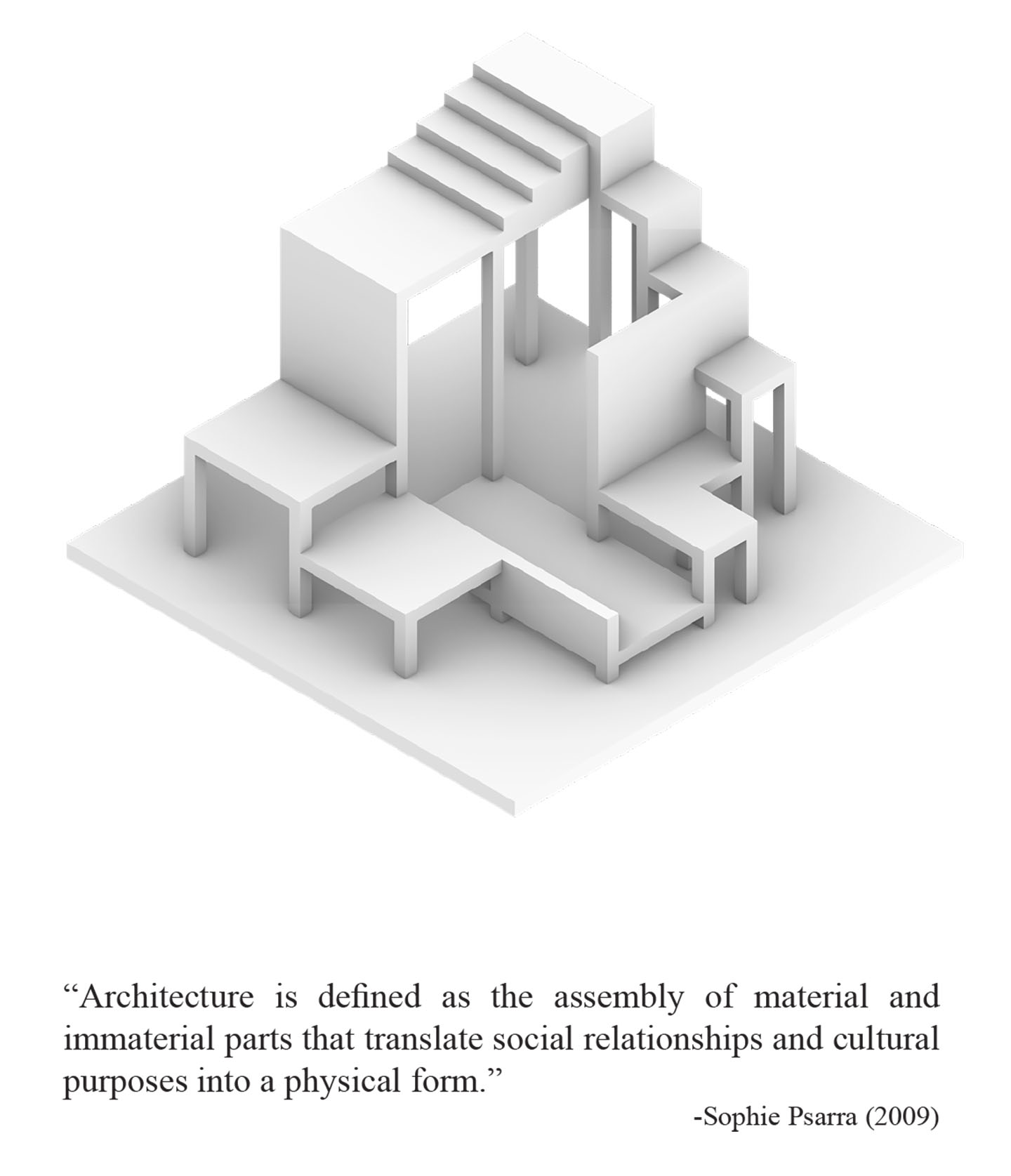

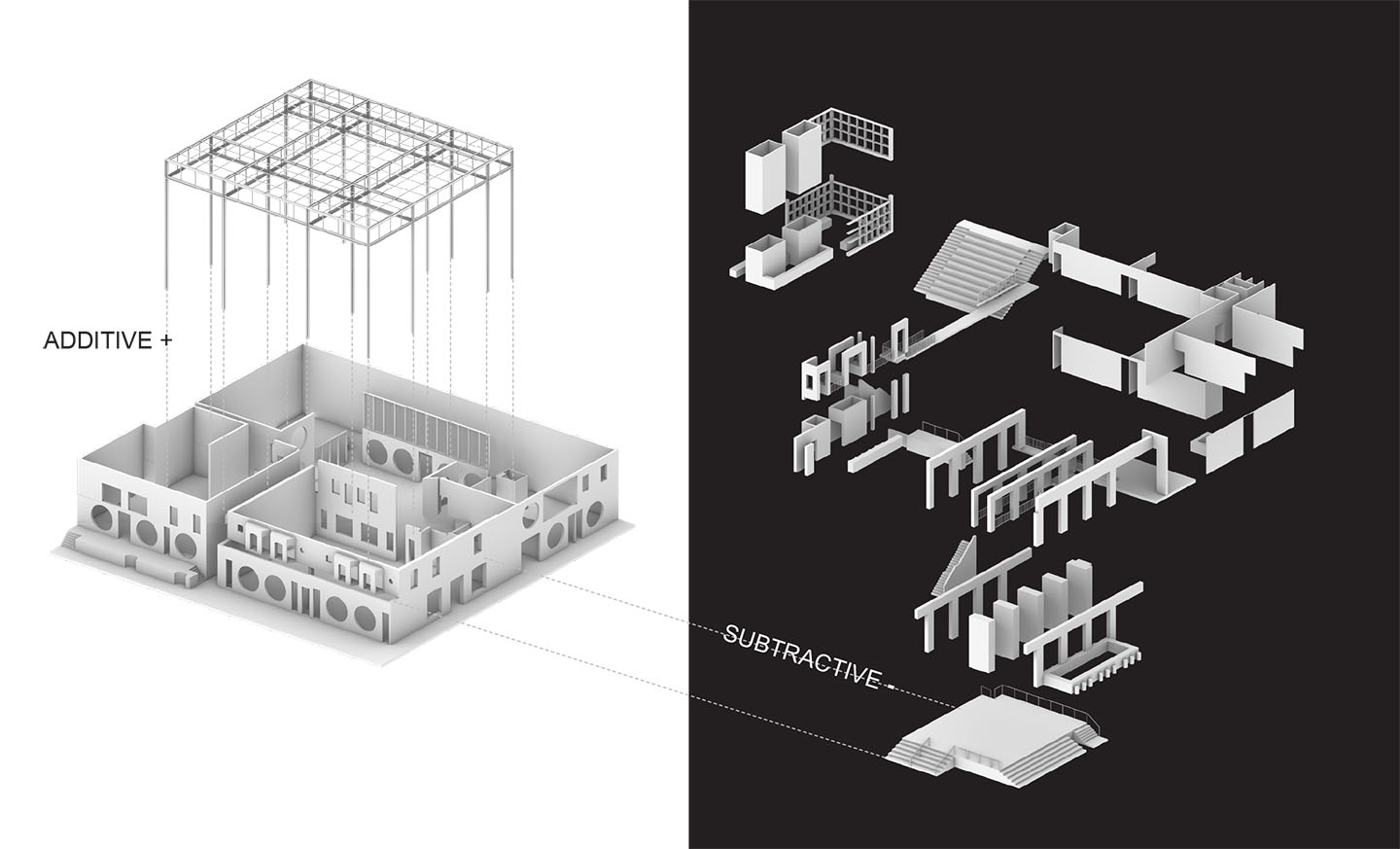

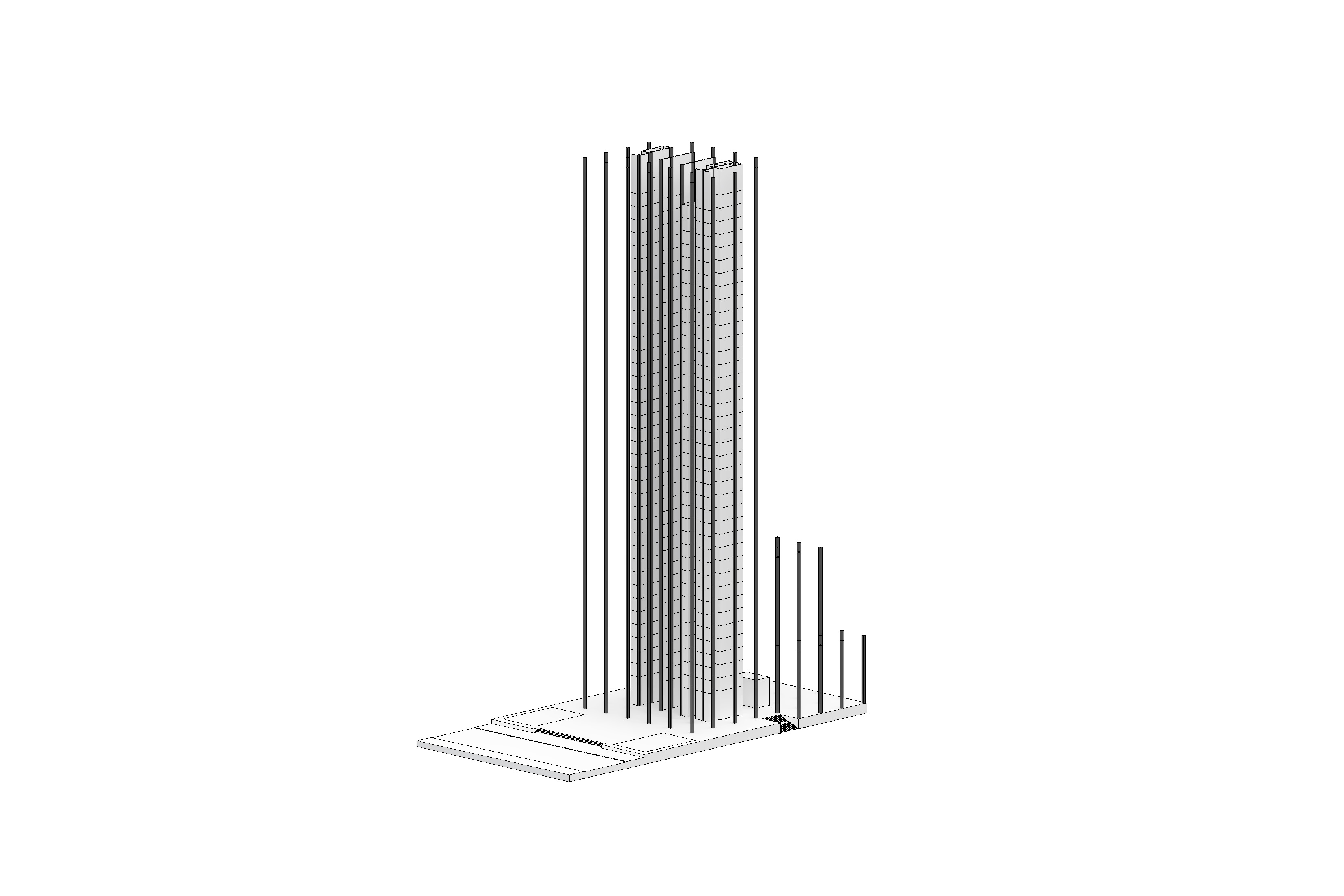

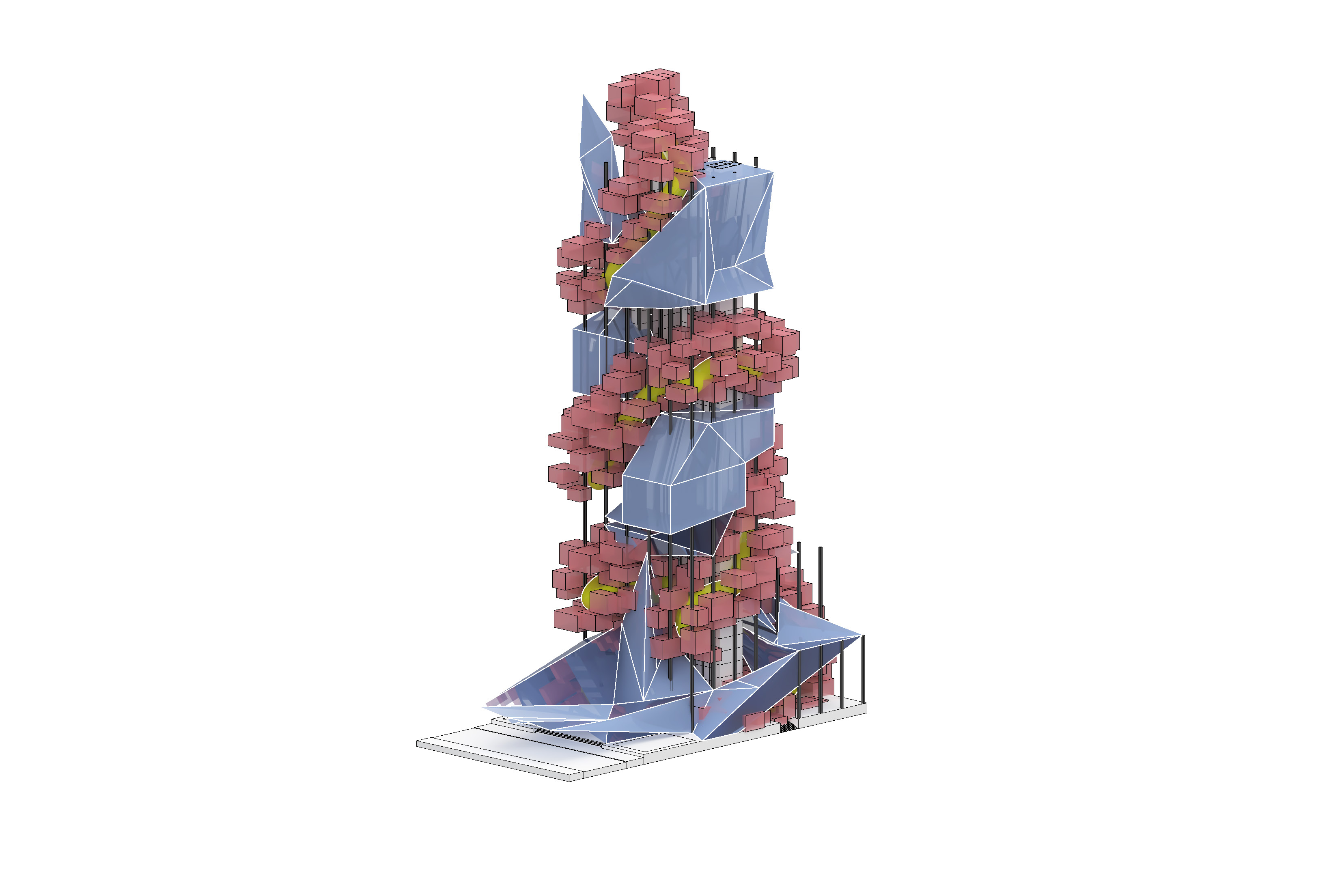

The intent of this project is to introduce the fundamental process of seeing architecture as a whole and the sum of its parts. Through a break down and reassembly of a small building, the Student will be exposed to the process of construction and the rationale of architectural form and aesthetic generation.

Project No. 2 - Architecture as a Whole and a Sum of its Parts

The intent of this project is to introduce the fundamental process of seeing architecture as a whole and the sum of its parts. Through a break down and reassembly of a small building, the Student will be exposed to the process of construction and the rationale of architectural form and aesthetic generation.

Mary Gozum

The intent of this project is to introduce the fundamental process of seeing architecture as a whole and the sum of its parts. Through a break down and reassembly of a small building, the Student will be exposed to the process of construction and the rationale of architectural form and aesthetic generation.

Project No. 2 - Architecture as a Whole and a Sum of its Parts

The intent of this project is to introduce the fundamental process of seeing architecture as a whole and the sum of its parts. Through a break down and reassembly of a small building, the Student will be exposed to the process of construction and the rationale of architectural form and aesthetic generation.

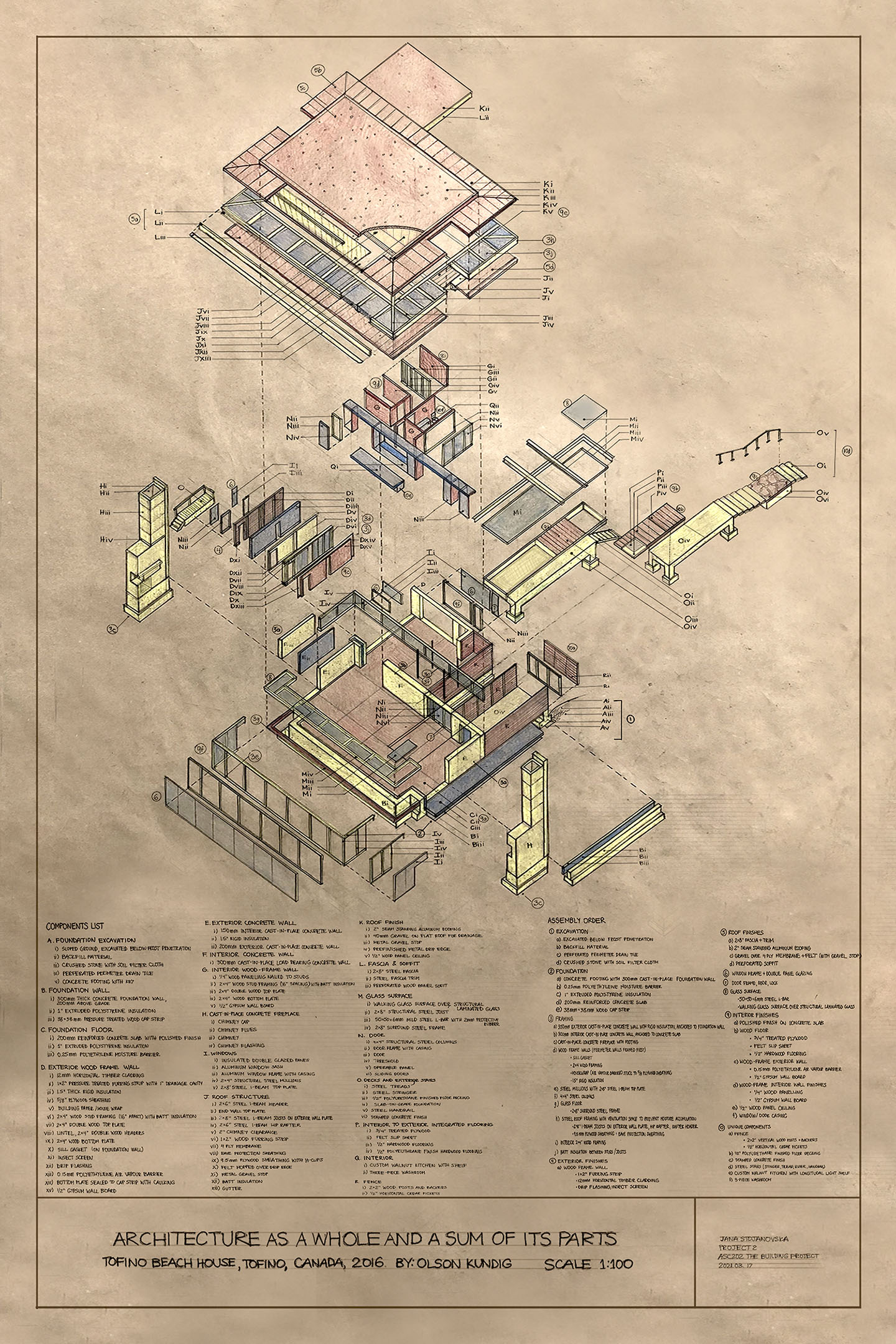

Jana Stojanovska

The intent of this project is to introduce the fundamental process of seeing architecture as a whole and the sum of its parts. Through a break down and reassembly of a small building, the Student will be exposed to the process of construction and the rationale of architectural form and aesthetic generation.

Project No. 2 - Architecture as a Whole and a Sum of its Parts

The intent of this project is to introduce the fundamental process of seeing architecture as a whole and the sum of its parts. Through a break down and reassembly of a small building, the Student will be exposed to the process of construction and the rationale of architectural form and aesthetic generation.

Jackson Rothenburg,

Julia Sider, Katy Cao, Muhammad Ghaffar Alhambra Palace

Alhambra Palace

The meaning of each monument must be analyzed within the context of the civilization from which it was created. Cultural, economic, social and other conditions should be understood and connected to demonstrate the meaning and the connection between time and place, and the language of architecture.

View full poster HERE.

View full poster HERE.

Christina Vo,

Jana Stojanovska,

Marc Fernandez, Nirav Mistry Saint Mark's Basilica

Saint Mark's Basilica

The history of architecture is a study of the built environments of humanity in all ages and places. In the broad survey of the ways, means and reasons why humans have shaped their built environments one would look at a number of significant structures which stand as prominent examples of that creative impulse. Each of these monuments, in its own way, in its time and place, stands as a representation of the aspiration, beliefs and values of its creators. Despite the separation in time and culture, we are able to appreciate these built environments and ‘decode’ their meaning as signifiers of their respectful civilizations.

View full poster HERE.

View full poster HERE.

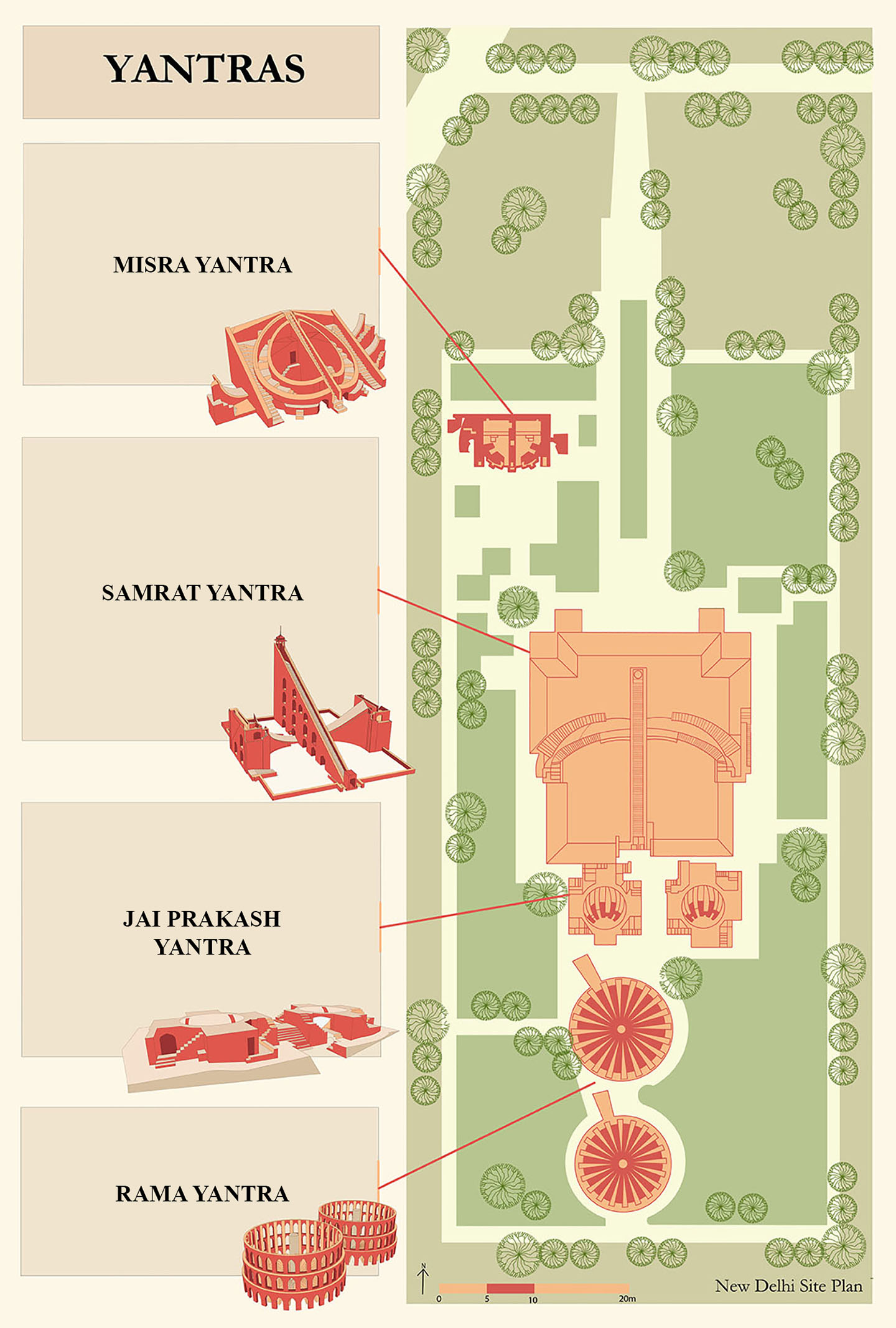

Amanda Lang, Charissa Medrano, Dea Permana, Erika ArriolaJantar Mantar

Jantar Mantar

Overview

The Jantar Mantars are astronomical observatories constructed at five sites in west-central India between 1724 and 1735.1 The first observatory was built at Delhi (shown here), followed by Mathura, Ujjain, Varanasi and Jaipur.1 These are open-air sites containing massive masonry instruments, called yantras, that are large enough to make astronomical observations with the naked eye.1

Cultural Context

Astronomy and cosmology were strongly linked to religious and philosophical beliefs in 18th-century India. It was widely believed that the gods communicated through celestial phenomena such as the movement and position of the stars.2 The accuracy of astronomical observations was deemed crucial as they impacted all aspects of life, from the scheduling of religious rituals and agricultural practices to decisions about marriage, succession or waging war.3

Arts and architectural works at the time were almost exclusively commissioned by the ruling Mughal emperors as expressions of social status.4 The Jantar Mantars were built to improve decision-making by correcting key astronomical records, such as the Table of Zij, and to create places for cosmological practitioners to gather.5

Design & Construction

Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, the regional ruler credited with building the Jantar Mantars, was an astronomer, a mathematician, a planner, and a scholar.6 He secured commissions from the Mughal Emperor to build the instruments after uncovering troubling discrepancies in existing astronomical records.6

Although telescopes were available, these massive instruments were favored in order to promote Indian religious and philosophical virtues such as interconnectedness, decentralization, and multiple uses.1 Enabling observers to scan the skies as a whole, orient themselves with particular celestial objects, and deepen their relationship with the universe promoted interconnectedness.1 Instrument design that required minimal training for use and allowed anyone to develop their own powers of observation and analysis served to decentralize access to knowledge.1 Multiple-use was incorporated by ensuring each instrument could be used to take a variety of readings.1 The construction of the Jantar Mantars was precise, using materials with perfect stability and paying close attention to geometry, location, and latitude.7 The composition of each instrument was based on the highly-respected Ptolemaic structure of positional astronomy.5 Although relatively unadorned, architectural details such as ogee arches, sandstone, and marble reflected the traditional Mughal style of architecture.4

View full poster HERE.

The Jantar Mantars are astronomical observatories constructed at five sites in west-central India between 1724 and 1735.1 The first observatory was built at Delhi (shown here), followed by Mathura, Ujjain, Varanasi and Jaipur.1 These are open-air sites containing massive masonry instruments, called yantras, that are large enough to make astronomical observations with the naked eye.1

Cultural Context

Astronomy and cosmology were strongly linked to religious and philosophical beliefs in 18th-century India. It was widely believed that the gods communicated through celestial phenomena such as the movement and position of the stars.2 The accuracy of astronomical observations was deemed crucial as they impacted all aspects of life, from the scheduling of religious rituals and agricultural practices to decisions about marriage, succession or waging war.3

Arts and architectural works at the time were almost exclusively commissioned by the ruling Mughal emperors as expressions of social status.4 The Jantar Mantars were built to improve decision-making by correcting key astronomical records, such as the Table of Zij, and to create places for cosmological practitioners to gather.5

Design & Construction

Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, the regional ruler credited with building the Jantar Mantars, was an astronomer, a mathematician, a planner, and a scholar.6 He secured commissions from the Mughal Emperor to build the instruments after uncovering troubling discrepancies in existing astronomical records.6

Although telescopes were available, these massive instruments were favored in order to promote Indian religious and philosophical virtues such as interconnectedness, decentralization, and multiple uses.1 Enabling observers to scan the skies as a whole, orient themselves with particular celestial objects, and deepen their relationship with the universe promoted interconnectedness.1 Instrument design that required minimal training for use and allowed anyone to develop their own powers of observation and analysis served to decentralize access to knowledge.1 Multiple-use was incorporated by ensuring each instrument could be used to take a variety of readings.1 The construction of the Jantar Mantars was precise, using materials with perfect stability and paying close attention to geometry, location, and latitude.7 The composition of each instrument was based on the highly-respected Ptolemaic structure of positional astronomy.5 Although relatively unadorned, architectural details such as ogee arches, sandstone, and marble reflected the traditional Mughal style of architecture.4

View full poster HERE.

MISRA YANTRA

Well known for its ‘heart shaped form’, the Misra Yantra utilizes five instruments that work

together to identify the longest and shortest days of the year.1 It is also capable of indicating noon

in various locations, regardless of their distance from the Dehli site.1 It is the only instrument

that was not constructed by Jai Singh II, but by his son after his passing.1

SAMRAT YANTRA

Also known as the “Supreme Instrument,” the Samrat Yantra is a large equinoctial sundial.1 It measures time precisely to an accuracy of two seconds.1 It is approximately 70 ft. high and 10 ft.thick with a triangle-shaped body called the gnomon in the centre.1 On a sunny day when the sun passes, the shadow cast by the gnomon falls onto the scale of the quadrants which indicates the time in hours, minutes, and seconds.1 The one in Jaipur is considered the world’s largest sundial.1

JAI PRAKASH YANTRA

The Jai Prakash Yantra is two hollowed out hemispheres with different markings on the interior surface.1 Each bowl shape has a crosswire and sighting plate across the top which allows the observer to make observations from below the instrument.1 It can also provide the coordinates of celestial objects in the sky.1

RAMA YANTRA

The Rama Yantra consists of two large cylindrical structures that measure the altitude of the stars and planets and the azimuth (the angle between North around the observer’s horizon and a celestial body).1

Well known for its ‘heart shaped form’, the Misra Yantra utilizes five instruments that work

together to identify the longest and shortest days of the year.1 It is also capable of indicating noon

in various locations, regardless of their distance from the Dehli site.1 It is the only instrument

that was not constructed by Jai Singh II, but by his son after his passing.1

SAMRAT YANTRA

Also known as the “Supreme Instrument,” the Samrat Yantra is a large equinoctial sundial.1 It measures time precisely to an accuracy of two seconds.1 It is approximately 70 ft. high and 10 ft.thick with a triangle-shaped body called the gnomon in the centre.1 On a sunny day when the sun passes, the shadow cast by the gnomon falls onto the scale of the quadrants which indicates the time in hours, minutes, and seconds.1 The one in Jaipur is considered the world’s largest sundial.1

JAI PRAKASH YANTRA

The Jai Prakash Yantra is two hollowed out hemispheres with different markings on the interior surface.1 Each bowl shape has a crosswire and sighting plate across the top which allows the observer to make observations from below the instrument.1 It can also provide the coordinates of celestial objects in the sky.1

RAMA YANTRA

The Rama Yantra consists of two large cylindrical structures that measure the altitude of the stars and planets and the azimuth (the angle between North around the observer’s horizon and a celestial body).1

1. Mukherji, Anisha Shekhar. "Time and Space in the Jantar Mantars." In Celestial Mirror: The Astronomical Observatories of Jai Singh II, by Perlus Barry, Ix-Xviii. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2020. Accessed February 23, 2021. doi:10.2307/j.ctv12fw7

2. Vellu, Iswen. Jantar Mantar: The Science of Indian Conjecture. www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/India/Rajasthan/HTML/Jantar%20Mantar.pdf.

3. The Astronomical Observatories of Jai Singh. www.jantarmantar.org.

4. Blair, Sheila S., Jonathan M. Bloom, and R. Nath. "Mughal family." Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 21 Feb. 2021. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000060146.

5. UNESCO. “Nomination of The Jantar Mantar, Jaipur for Inclusion on World Heritage List.” 2010, https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1338.pdf. Accessed 18 February 2021.

6. The British Museum. n.d. Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG110197.

7. Sherring, Matthew Atmore. 1868. The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Varanasi: Trübner & Company. https://books.google.ca/books?id=HlQOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA134&lpg=PA134&dq=%22of+stone+and+lime+of+perfect+stability,+with+attention+to+the+rules+of+geometry+and+adjustment+to+the+meridian+and+to+the+latitude+of+the+place%22&source=bl&ots=tA5_dkrFpb&sig=ACfU3U0S.

8. Winzer, A. 2005. File:Jantar Mantar Delhi 27-05-2005.jpg. June 12. Accessed March 27, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jantar_Mantar_Delhi_27-05-2005.jpg.

2. Vellu, Iswen. Jantar Mantar: The Science of Indian Conjecture. www.tracyanddale.50megs.com/India/Rajasthan/HTML/Jantar%20Mantar.pdf.

3. The Astronomical Observatories of Jai Singh. www.jantarmantar.org.

4. Blair, Sheila S., Jonathan M. Bloom, and R. Nath. "Mughal family." Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 21 Feb. 2021. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000060146.

5. UNESCO. “Nomination of The Jantar Mantar, Jaipur for Inclusion on World Heritage List.” 2010, https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/nominations/1338.pdf. Accessed 18 February 2021.

6. The British Museum. n.d. Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II. Accessed March 11, 2021. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG110197.

7. Sherring, Matthew Atmore. 1868. The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Varanasi: Trübner & Company. https://books.google.ca/books?id=HlQOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA134&lpg=PA134&dq=%22of+stone+and+lime+of+perfect+stability,+with+attention+to+the+rules+of+geometry+and+adjustment+to+the+meridian+and+to+the+latitude+of+the+place%22&source=bl&ots=tA5_dkrFpb&sig=ACfU3U0S.

8. Winzer, A. 2005. File:Jantar Mantar Delhi 27-05-2005.jpg. June 12. Accessed March 27, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jantar_Mantar_Delhi_27-05-2005.jpg.

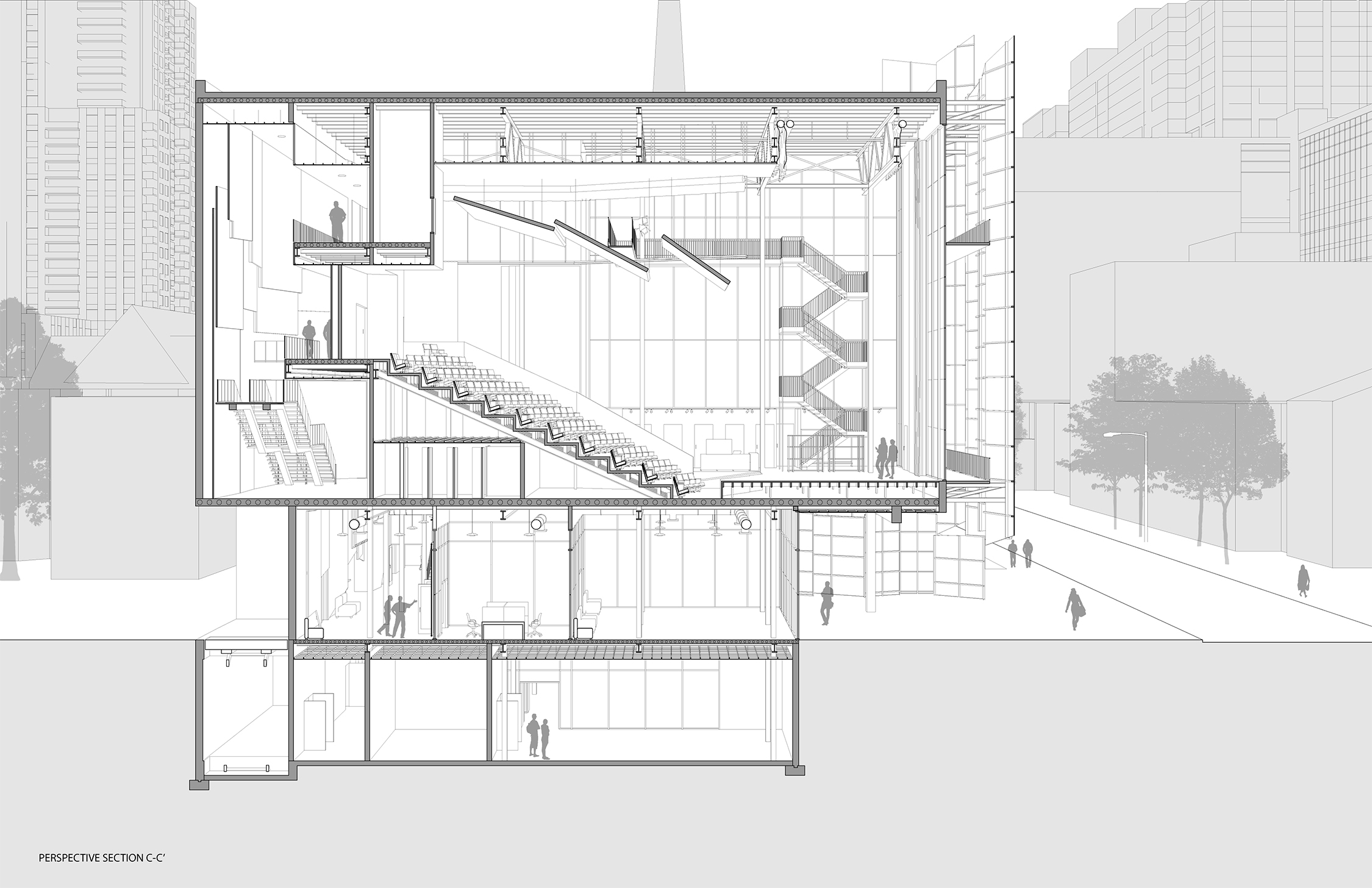

Justin Lieberman

Deflection Theatre

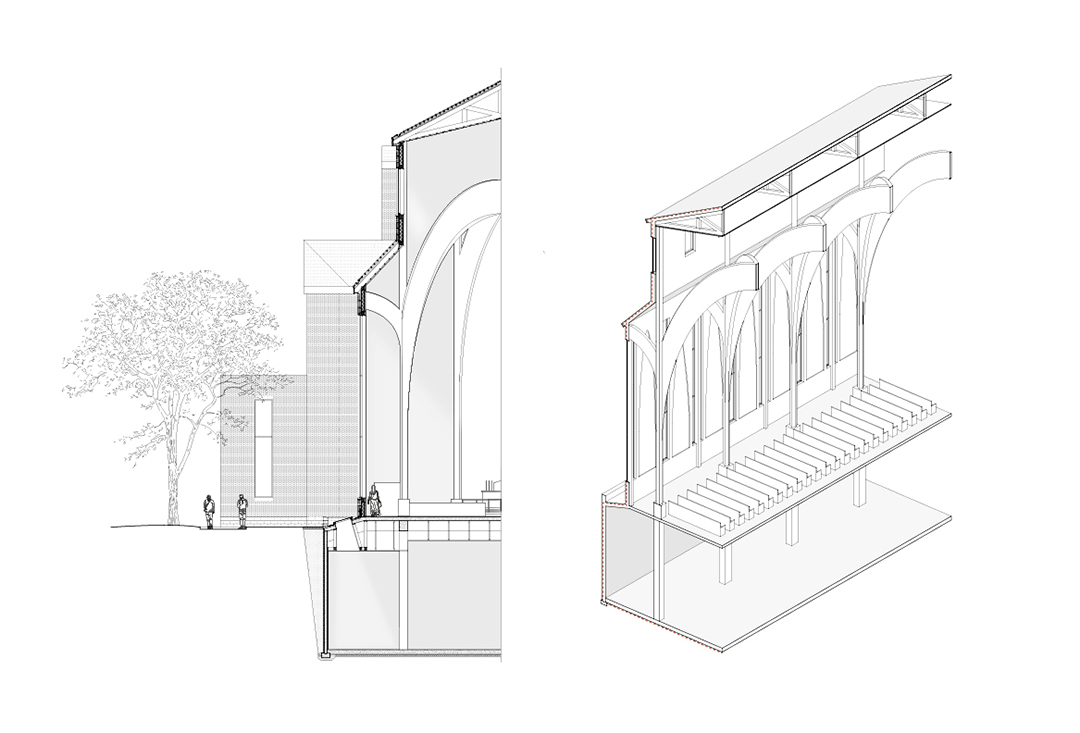

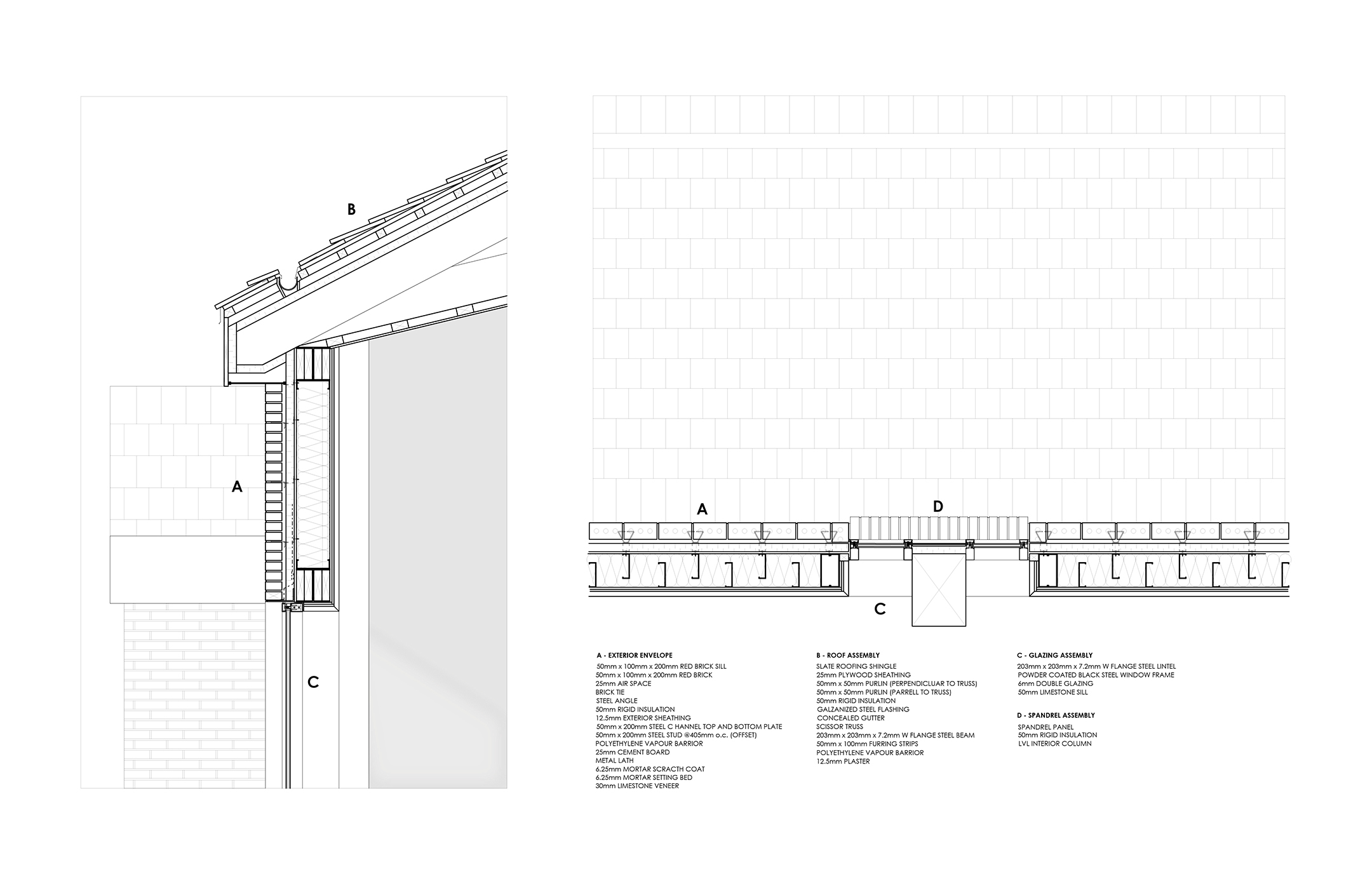

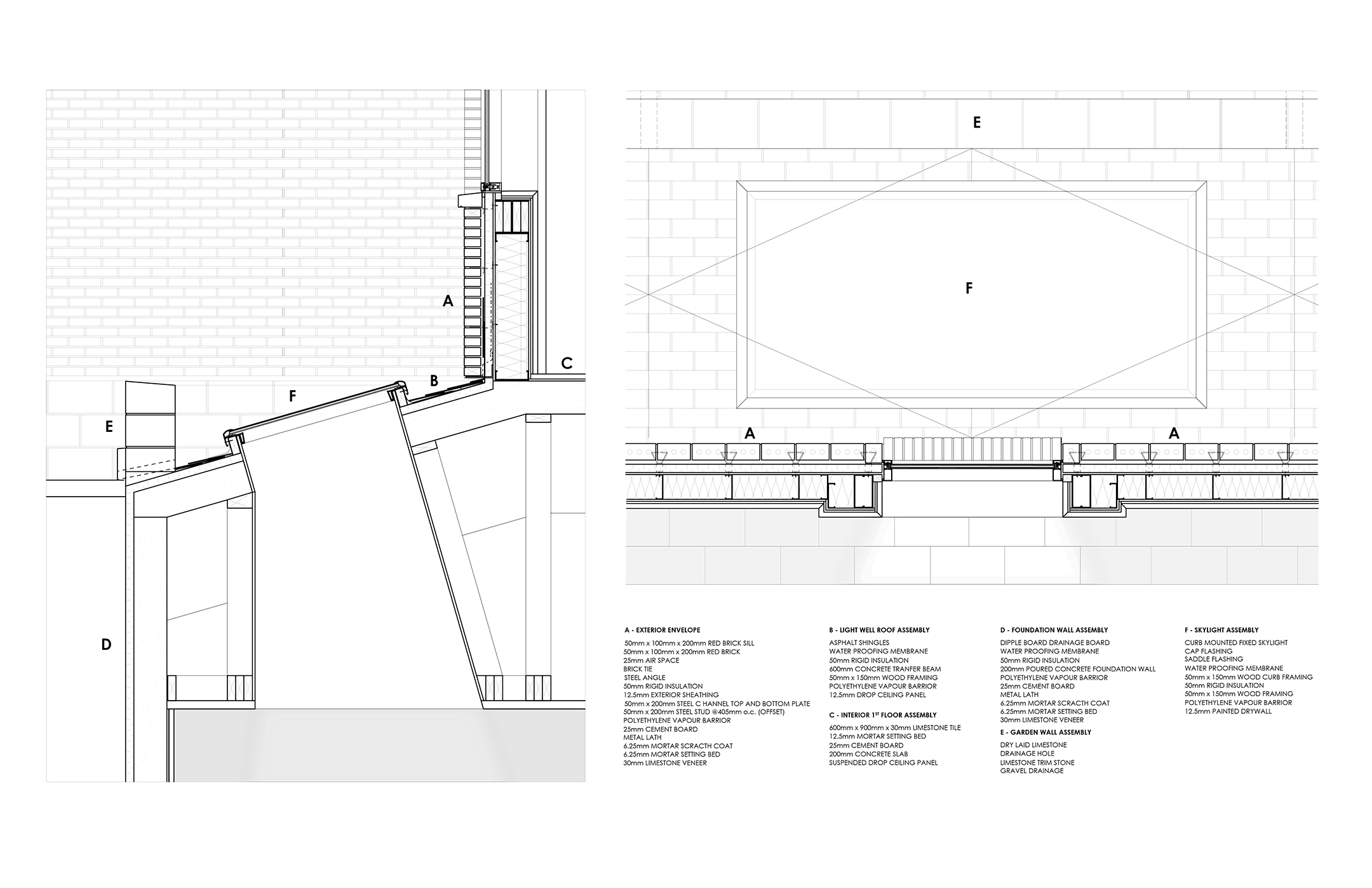

Deflection Theatre uses specific curved gestures to allow light to be deflected and absorbed into spaces. Natural and artificial light deflects and travels along materiality's to illuminate each programmatic space. A specific louver system also reduces and controls sound transmission when vocal control is preferred. In the community spaces, the louver distancing is larger to allow for vocal and visual engagement. The building has community facilities at the forefront of Dundas Street, a light well for circulation, then near the back, the private stage space. Deflection Theatre uses curved gestures therefore allowing light to be reflected and absorbed, reduce sound transmission, and define programmatic location.

Hunter Kauremszky

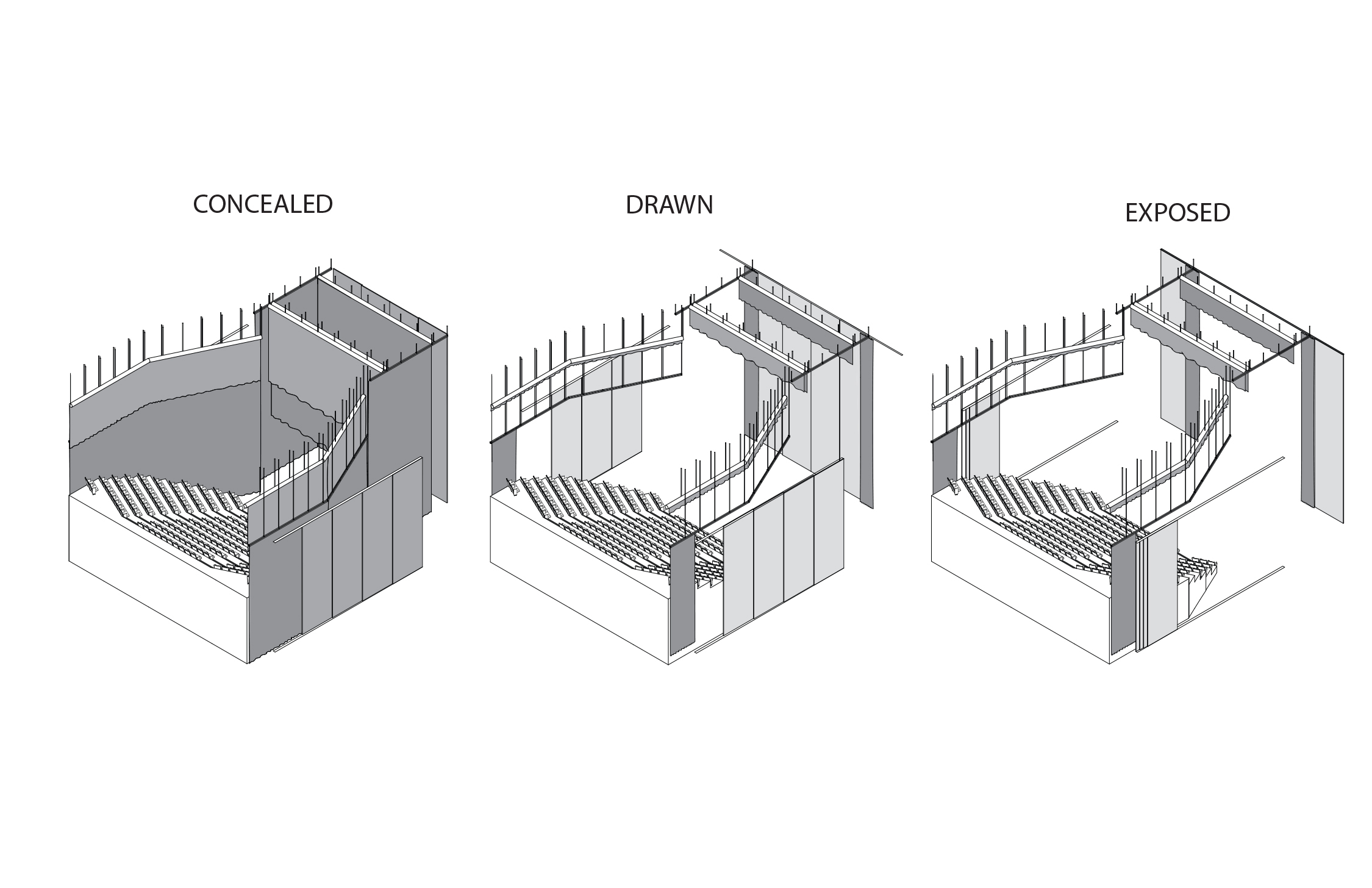

Veil and Expose

Veil and Expose

Theatre is a carefully crafted art where the structure of the show – including the sound, the set, the lighting, the music, and the performers – come together to create the experience we see on stage. People can have a greater appreciation for the masquerade of theatre if the mechanics are revealed to them. This play between veil and expose is paramount to appreciating both the function and the experience of theatre.

The intent is to juxtapose transparency with concealment to draw attention to and celebrate the dual nature of theatre: performance and production.

ASC301 challenged us to explore the possible means by which an architectural intention can manifest itself in a project. The brief of the project was to design a modest performance hall with a performance of our choice that conveys a clear manifestation of an architectural intention through the use of several means of architectural expression (i.e. materiality, form, light and shadow).

The intent is to juxtapose transparency with concealment to draw attention to and celebrate the dual nature of theatre: performance and production.

ASC301 challenged us to explore the possible means by which an architectural intention can manifest itself in a project. The brief of the project was to design a modest performance hall with a performance of our choice that conveys a clear manifestation of an architectural intention through the use of several means of architectural expression (i.e. materiality, form, light and shadow).

Horia Curteanu

Reflective Duality

To embody the elements of duality found within the site to create a multi-functional and interconnected occupational volume. The specific themes of duality that were incorporated into the project are the themes nature and manmade, high and low, old and new. From the varying heights and locations that create different experiences and connections with the visitors, to the combination of organically shaped paneling to ramp up green spaces, all these decisions were a consequence of the built environment around the site.

Ariel Weiss

Superimposition

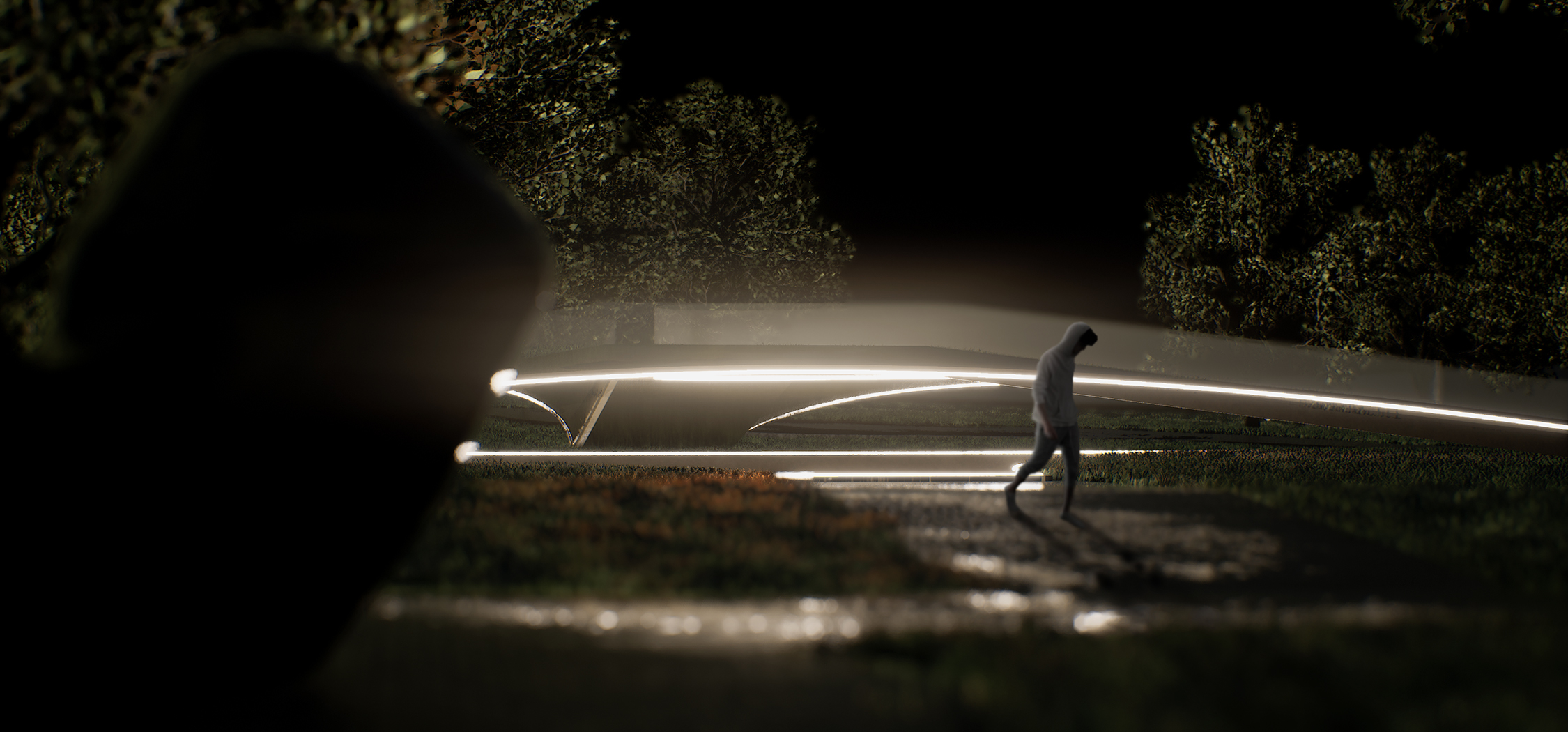

Located adjacent to the AGO in downtown Toronto, Grange Park is a historic park - turned active outdoor space for its surrounding residents. With the growing number of residents who live close to the park, as well as visitors who might use the park occasionally, Grange Park acts as a “backyard space” for its users. In creating a performance pavilion, Superimposition not only attempts to impose a new program onto the park but also strives to maintain and extend its existing program at the same time. The Pavilion is composed out of two mirrored forms. One being an extension of the existing program, and the other being an imposition of a new one. In using two opposing forms, the pavilion can achieve its dichotomous program. Its thin-shell concrete structure allows the upper form to maintain a subtle and informal program during the day, while its lower foundational form supports a distinct and formal program at night. The relationship between both of the two forms then becomes an embodiment of the coexistence between site and program.

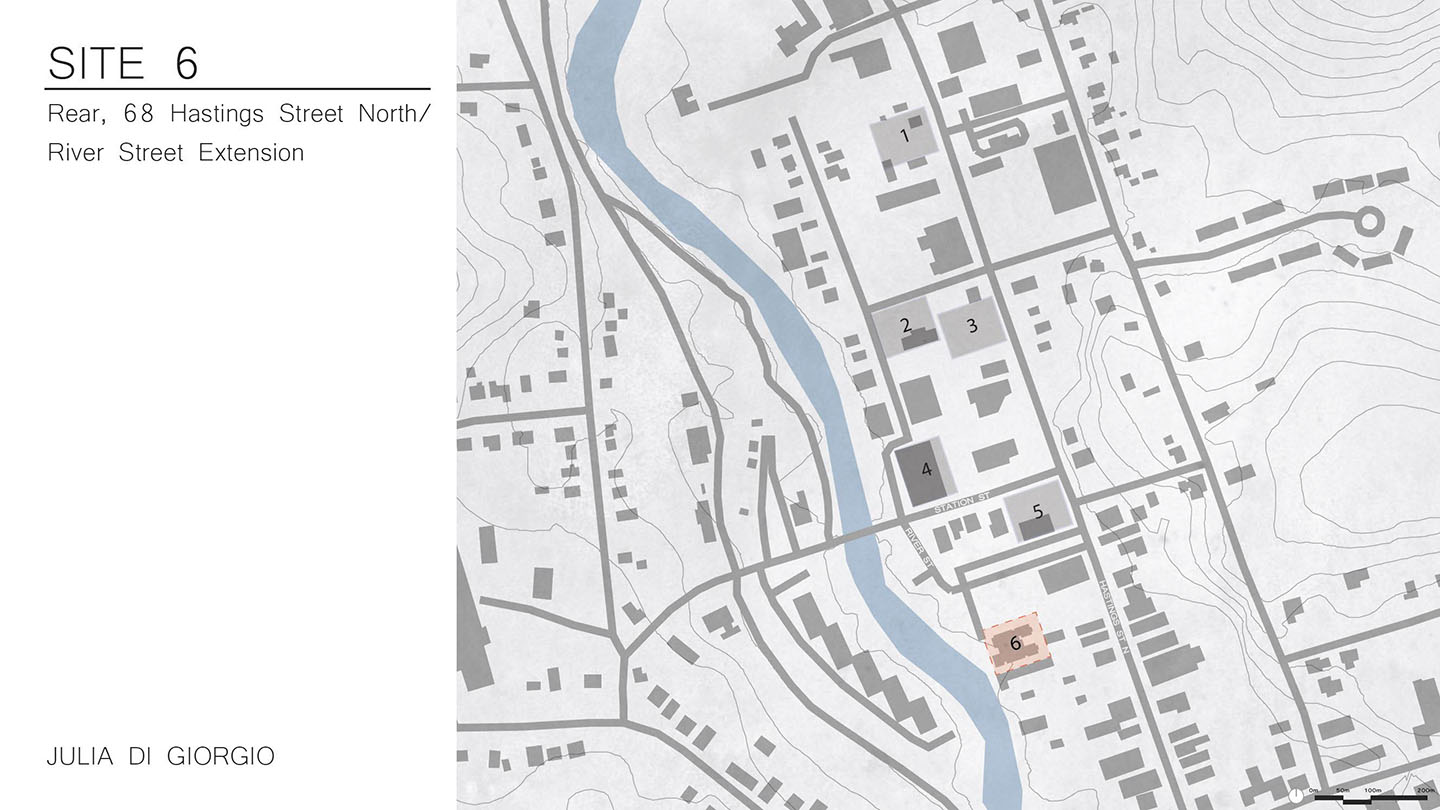

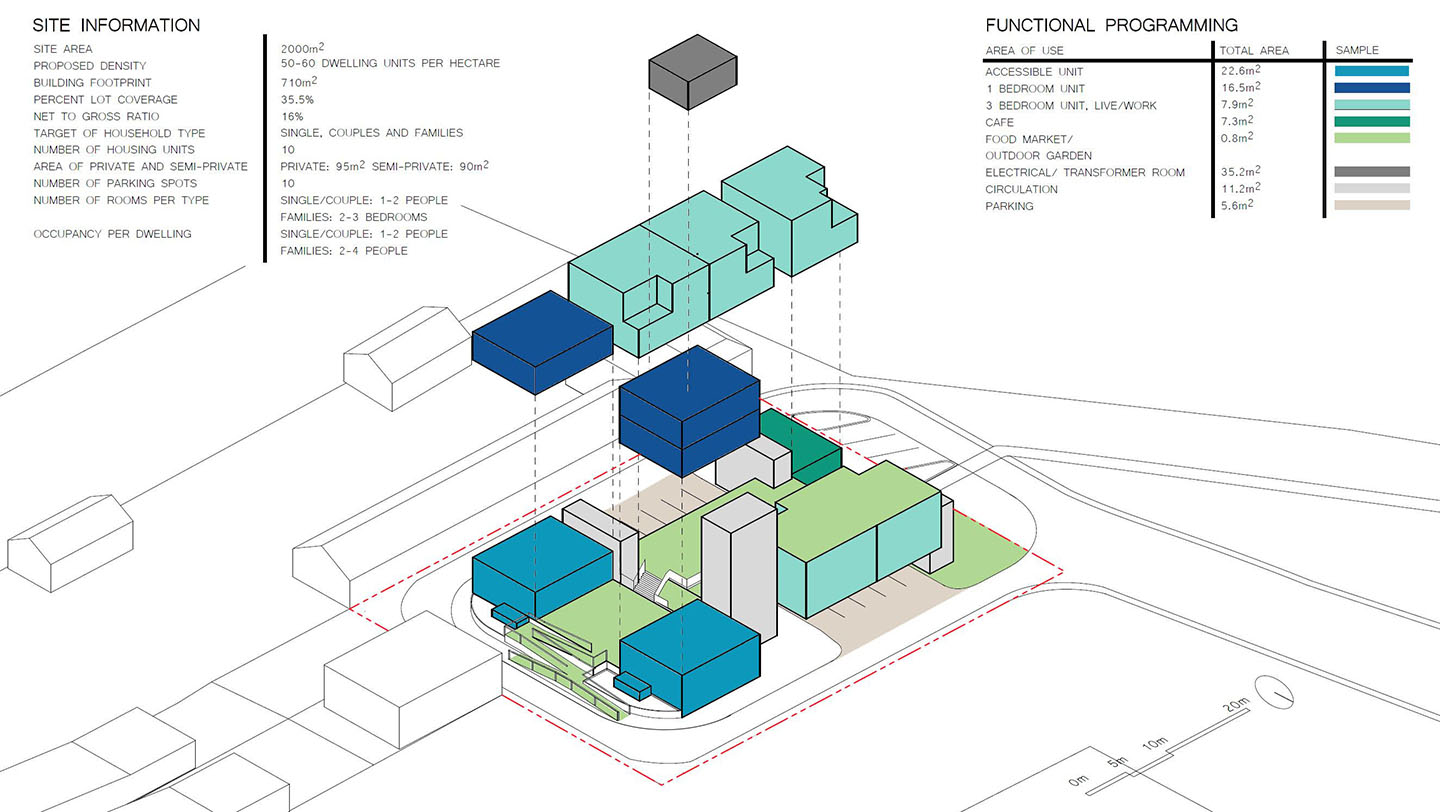

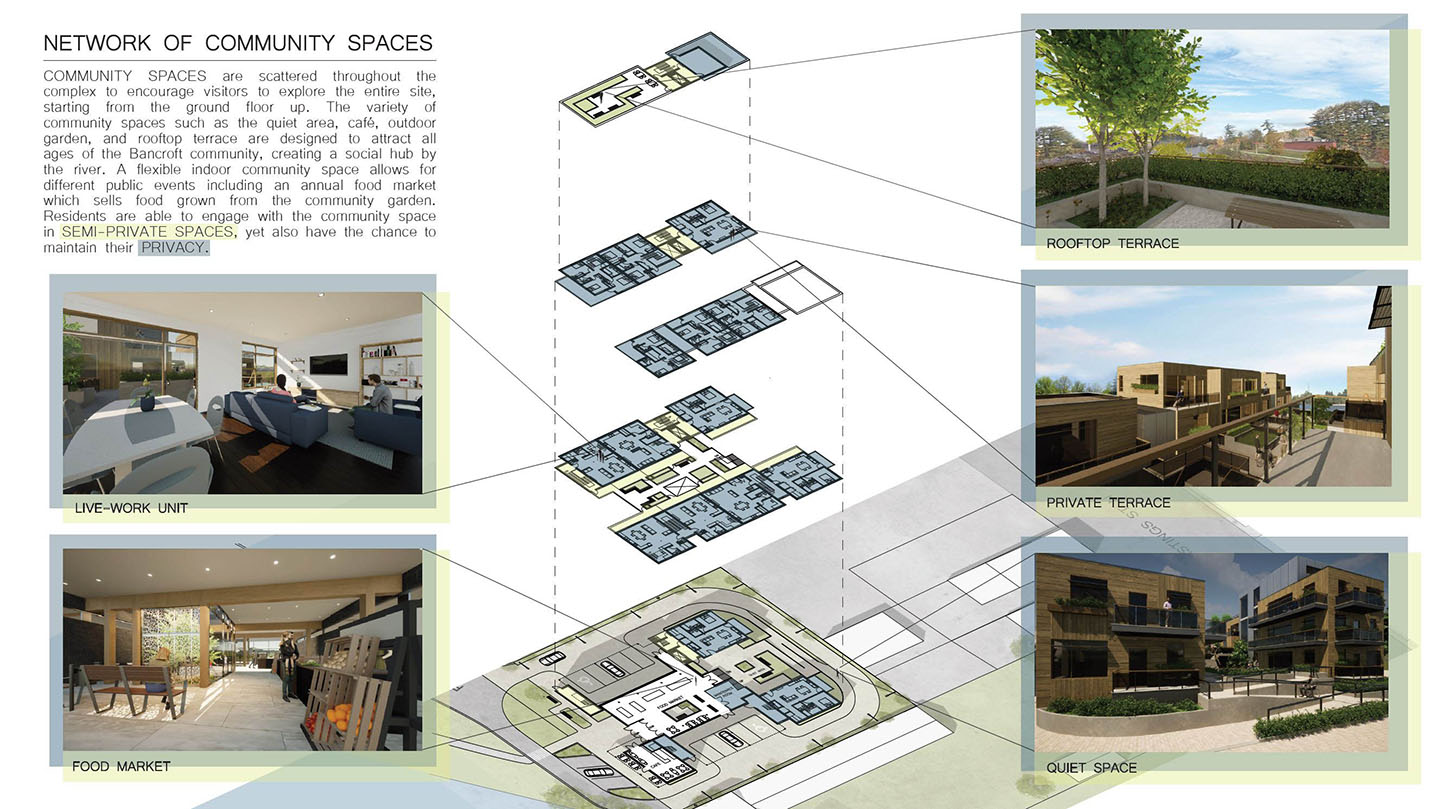

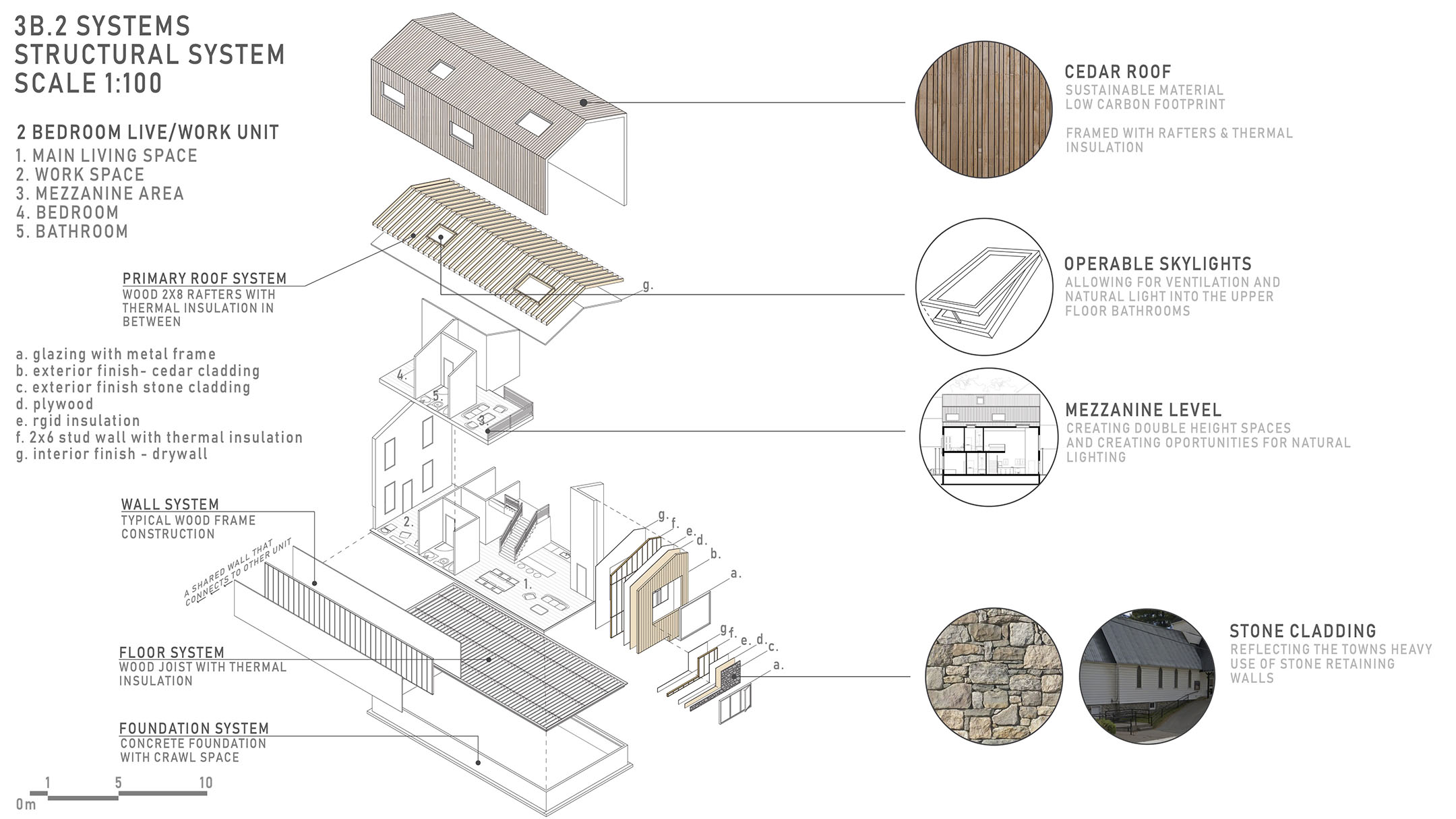

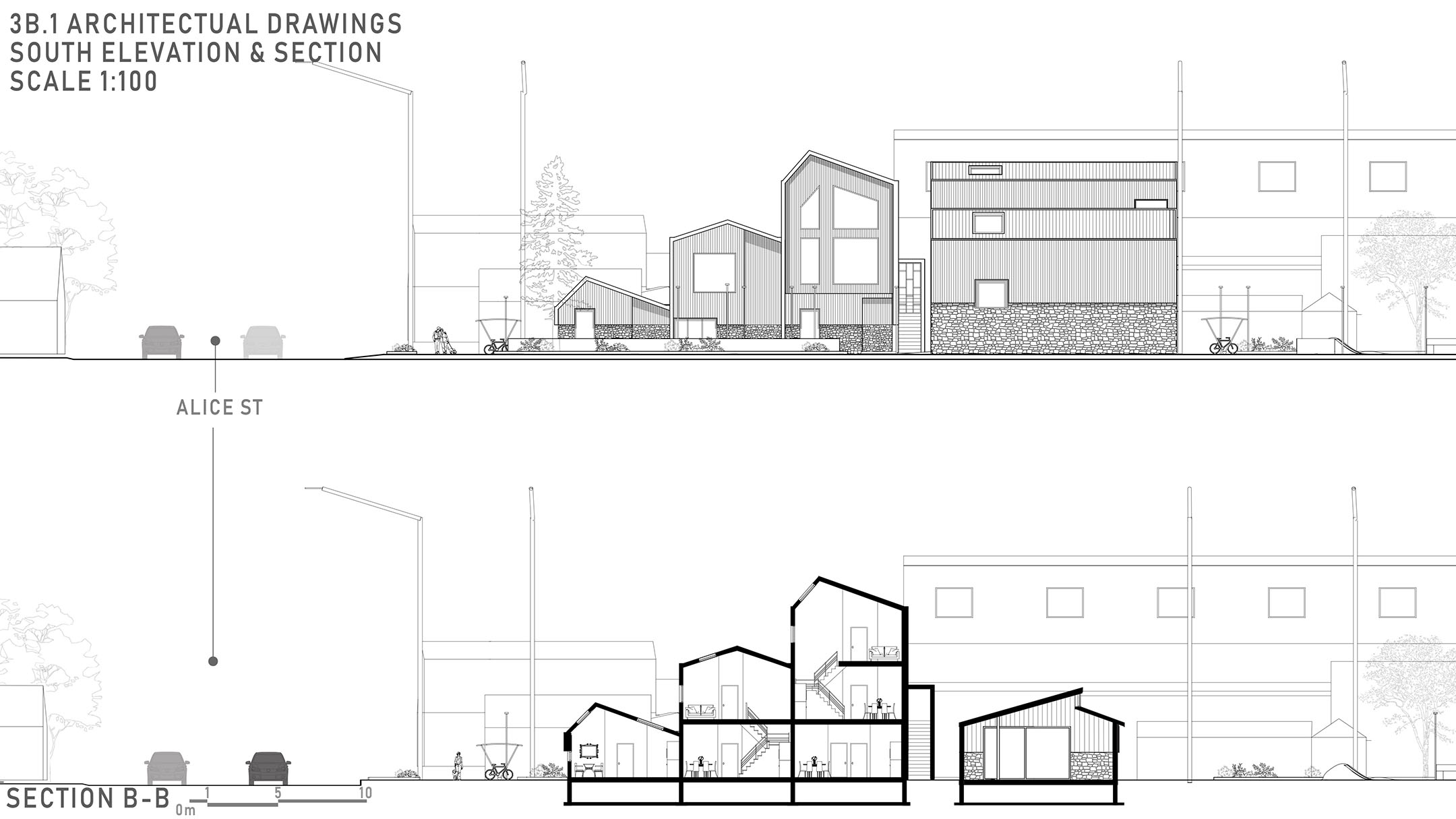

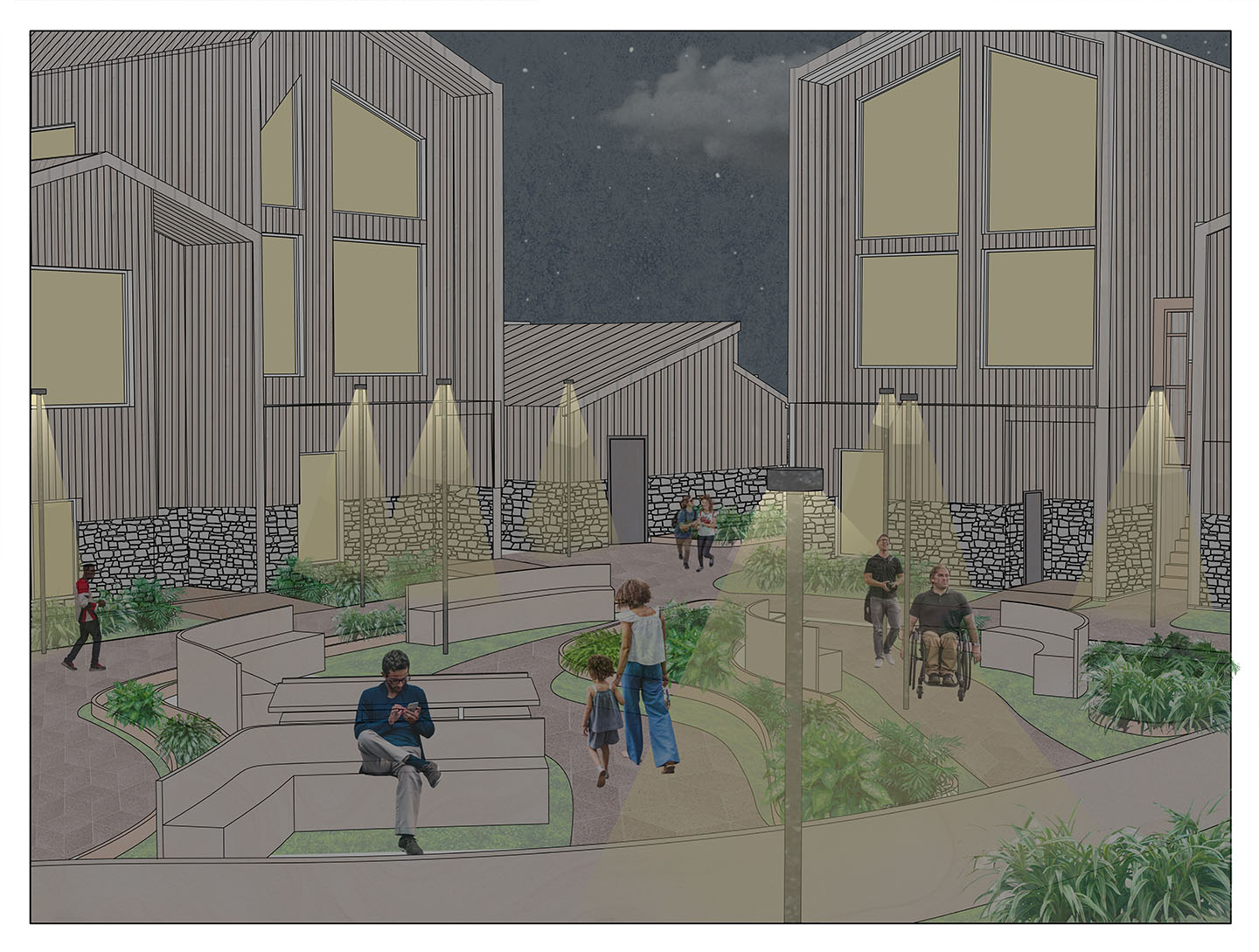

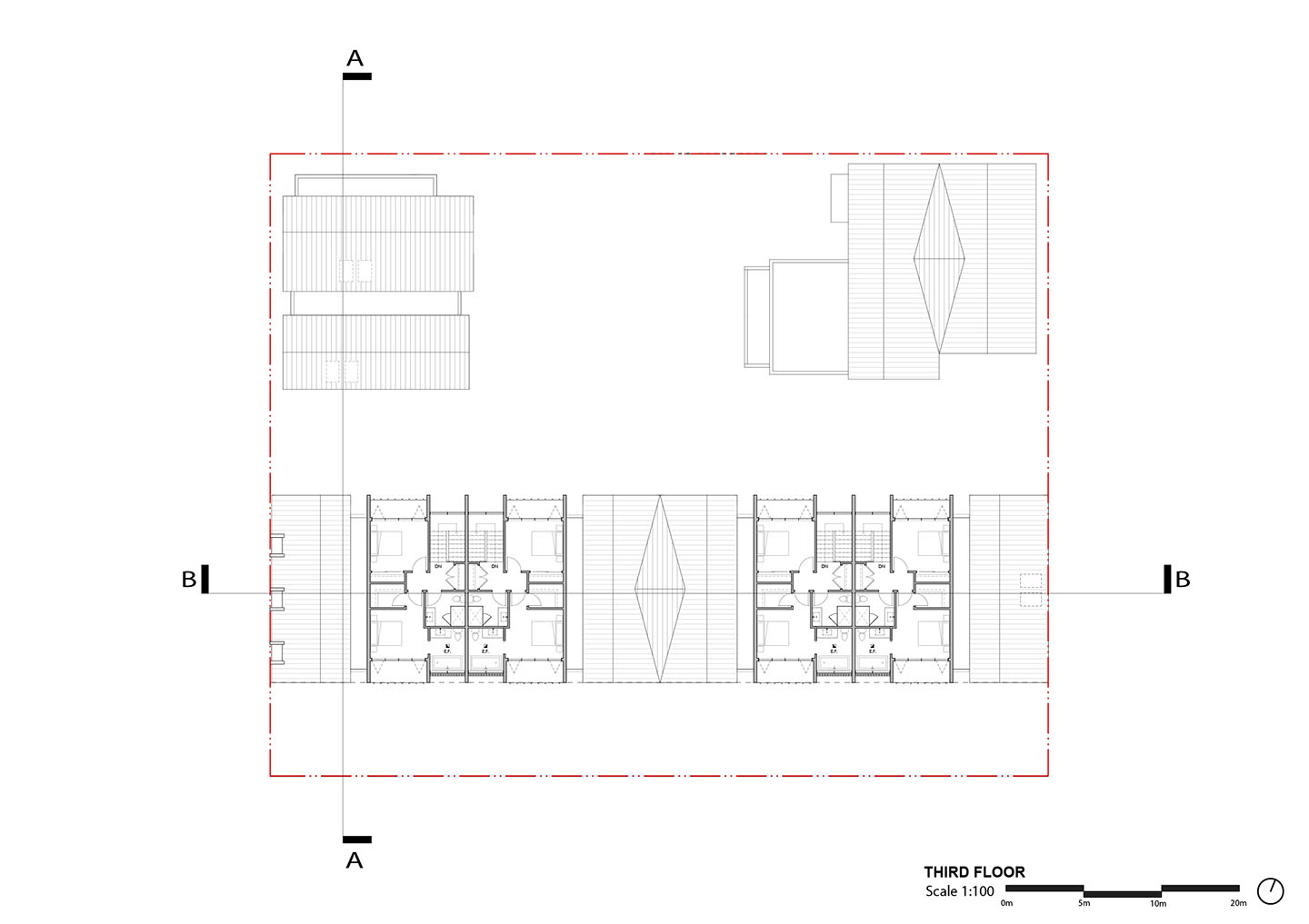

Ring Road Homes

The goal of this project is to develop a housing design in the Town of Bancroft. Community spaces, such as a quiet area, café, outdoor garden, and rooftop terrace, are scattered throughout the 10-unit complex to attract all ages of the Bancroft community, creating an inclusive social hub by the river. A flexible indoor community space allows for different public events including an annual food market, which sells food grown from the community garden. Residents can engage with the community in semi-private spaces located throughout the project, yet also maintain their privacy in residential zones.

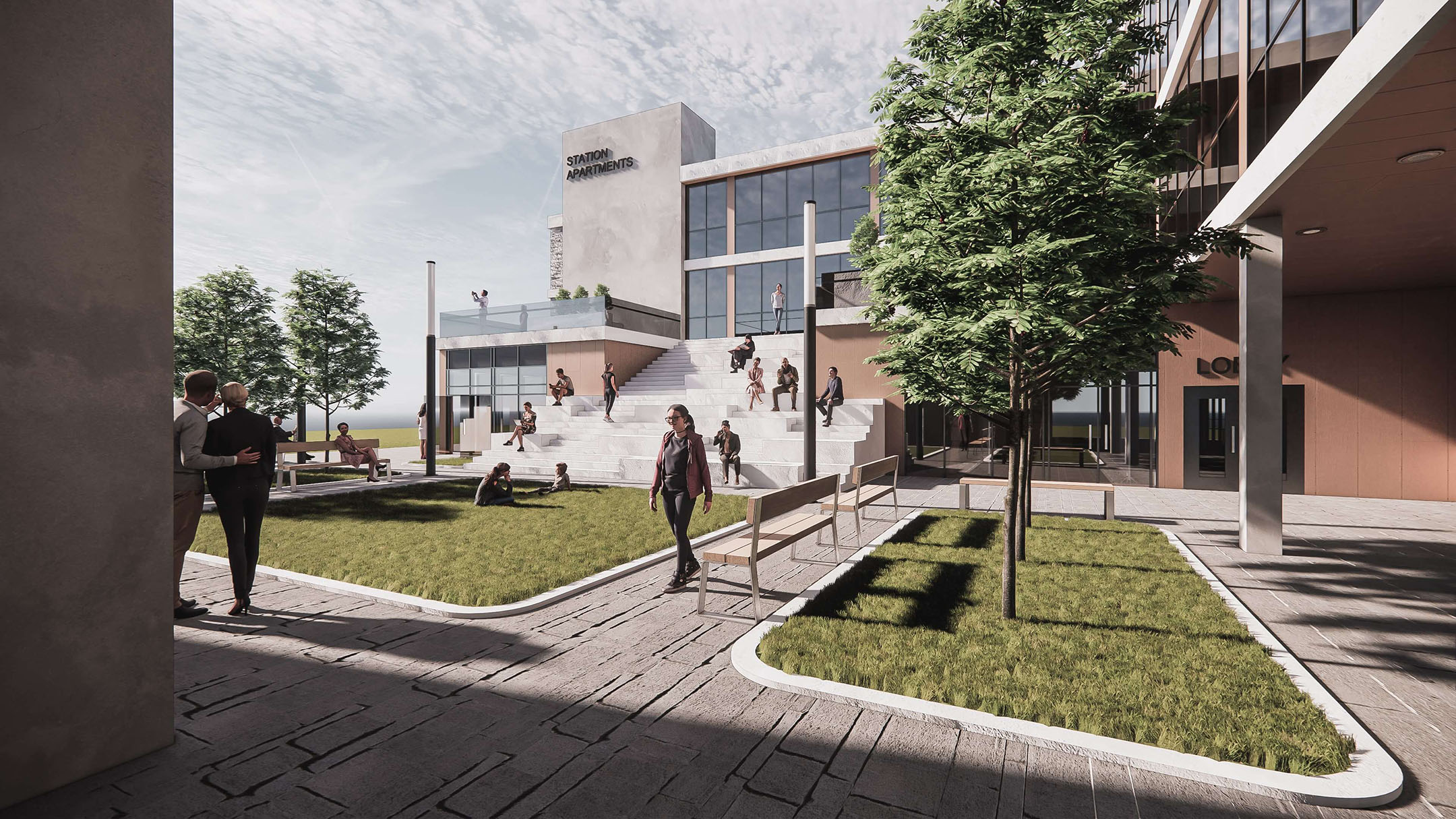

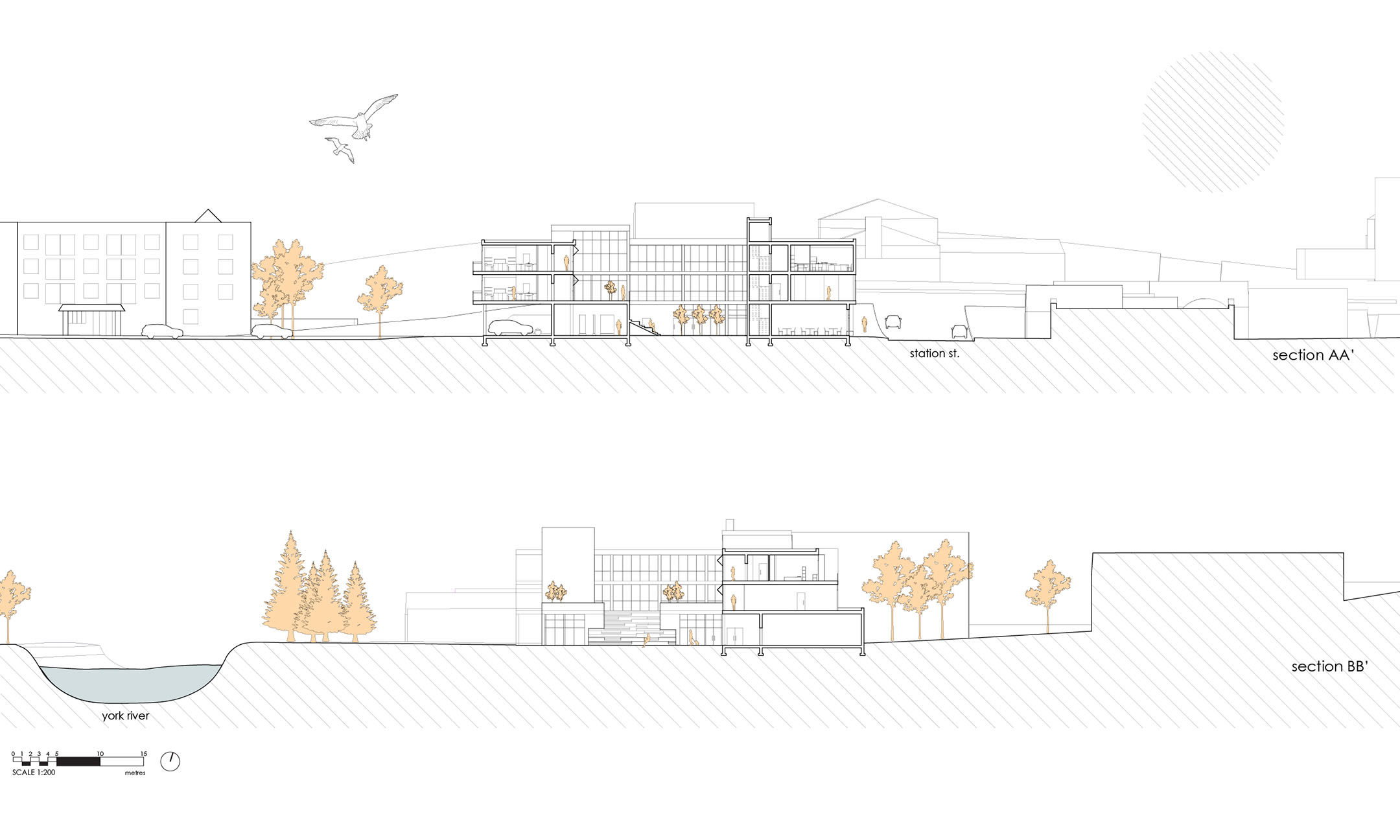

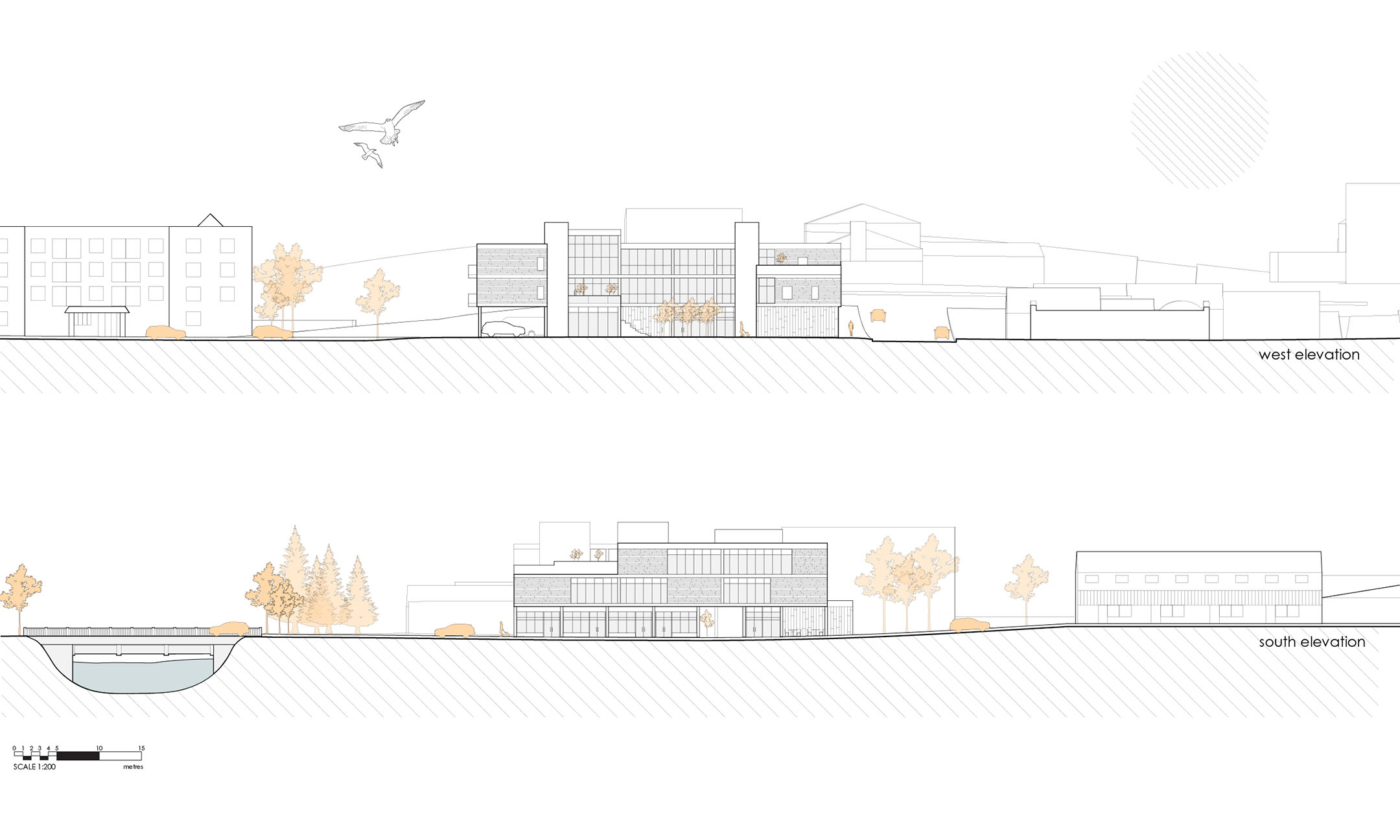

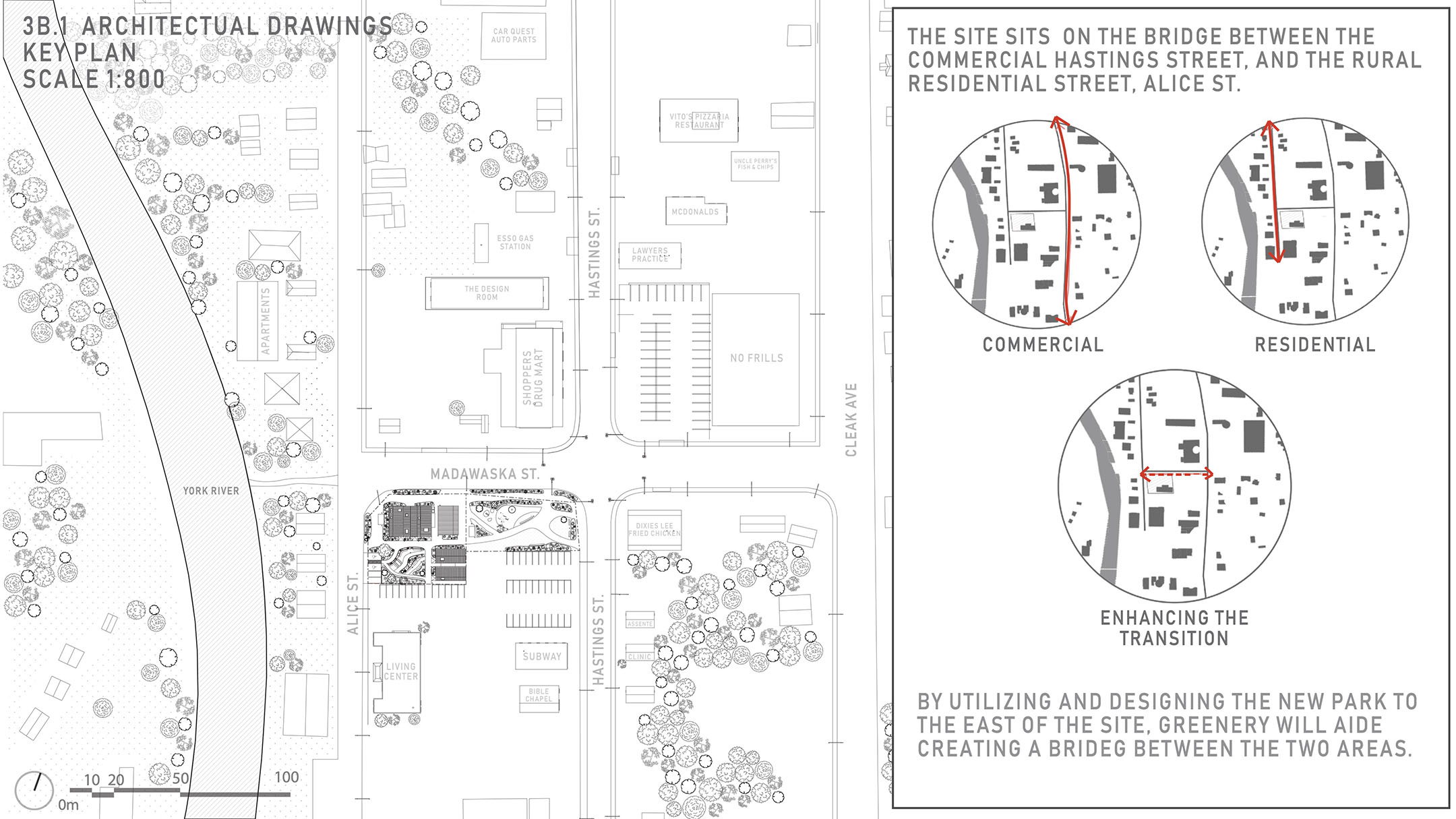

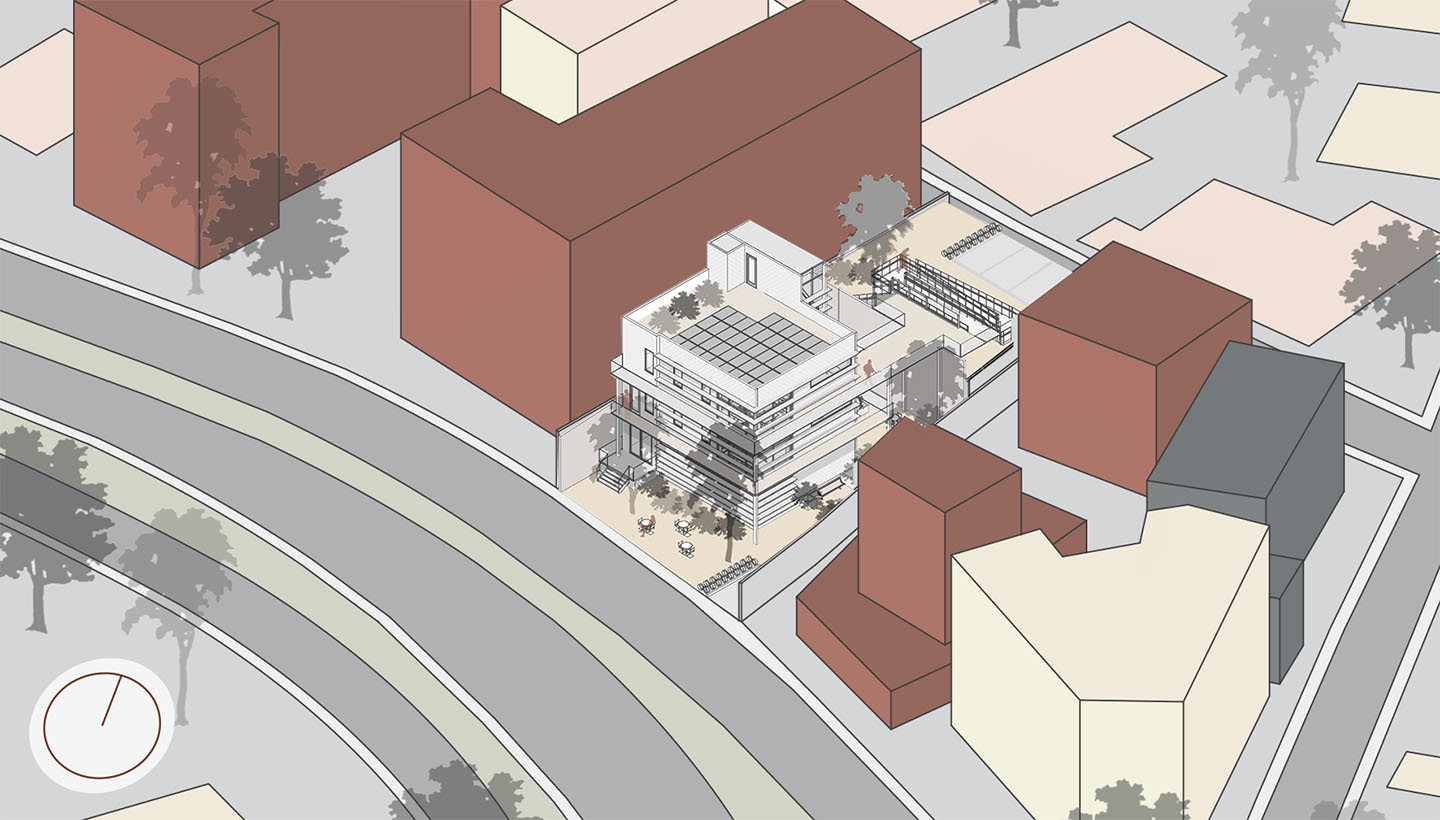

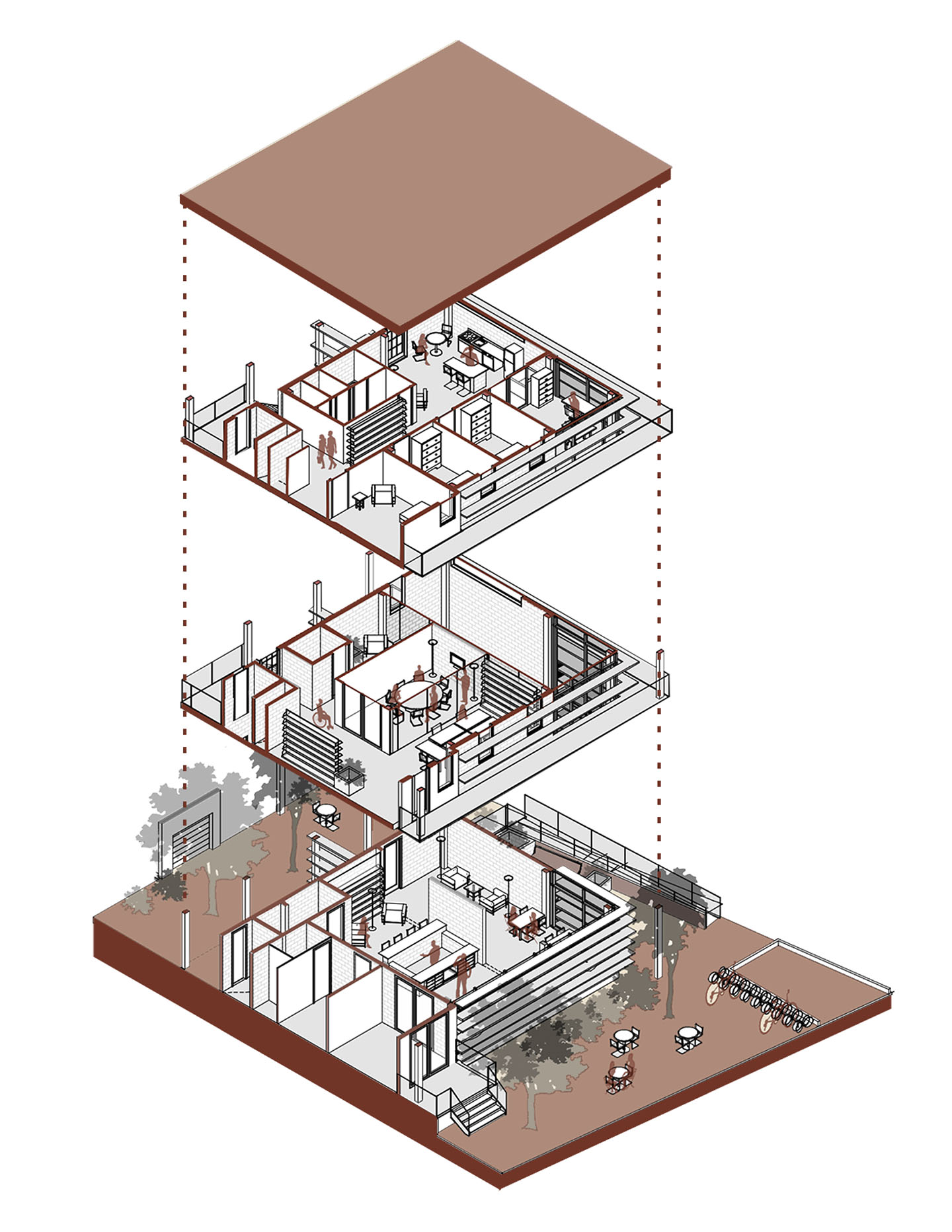

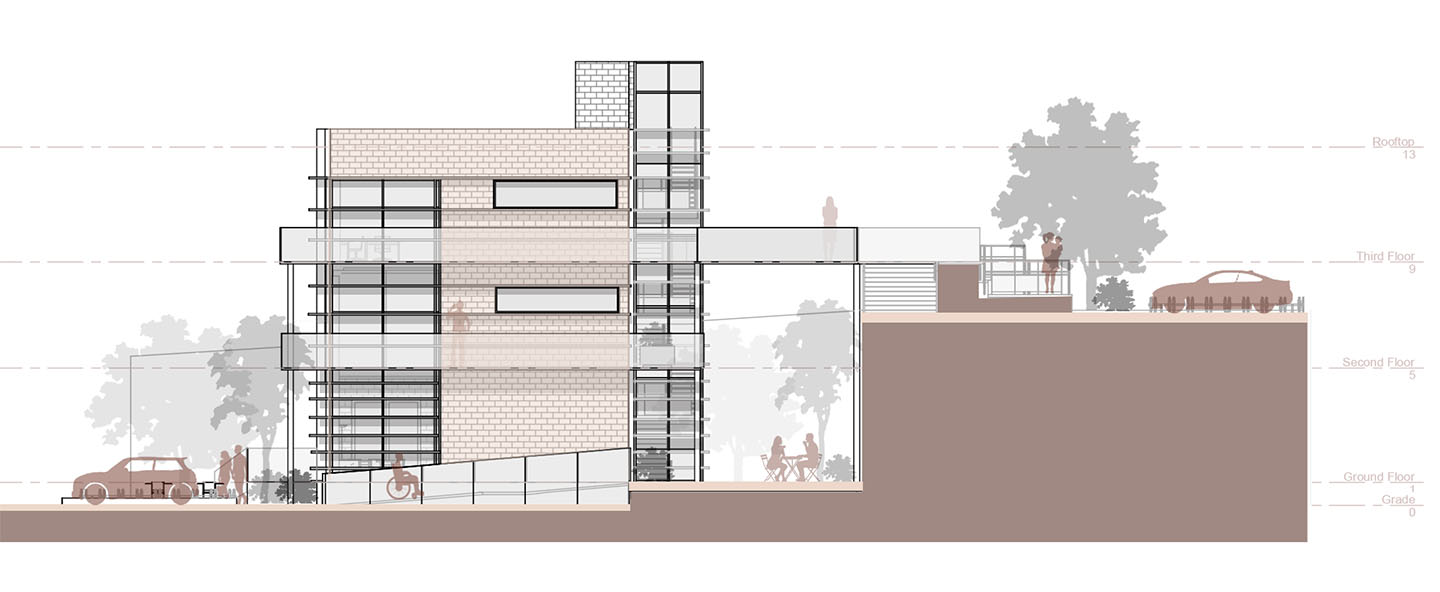

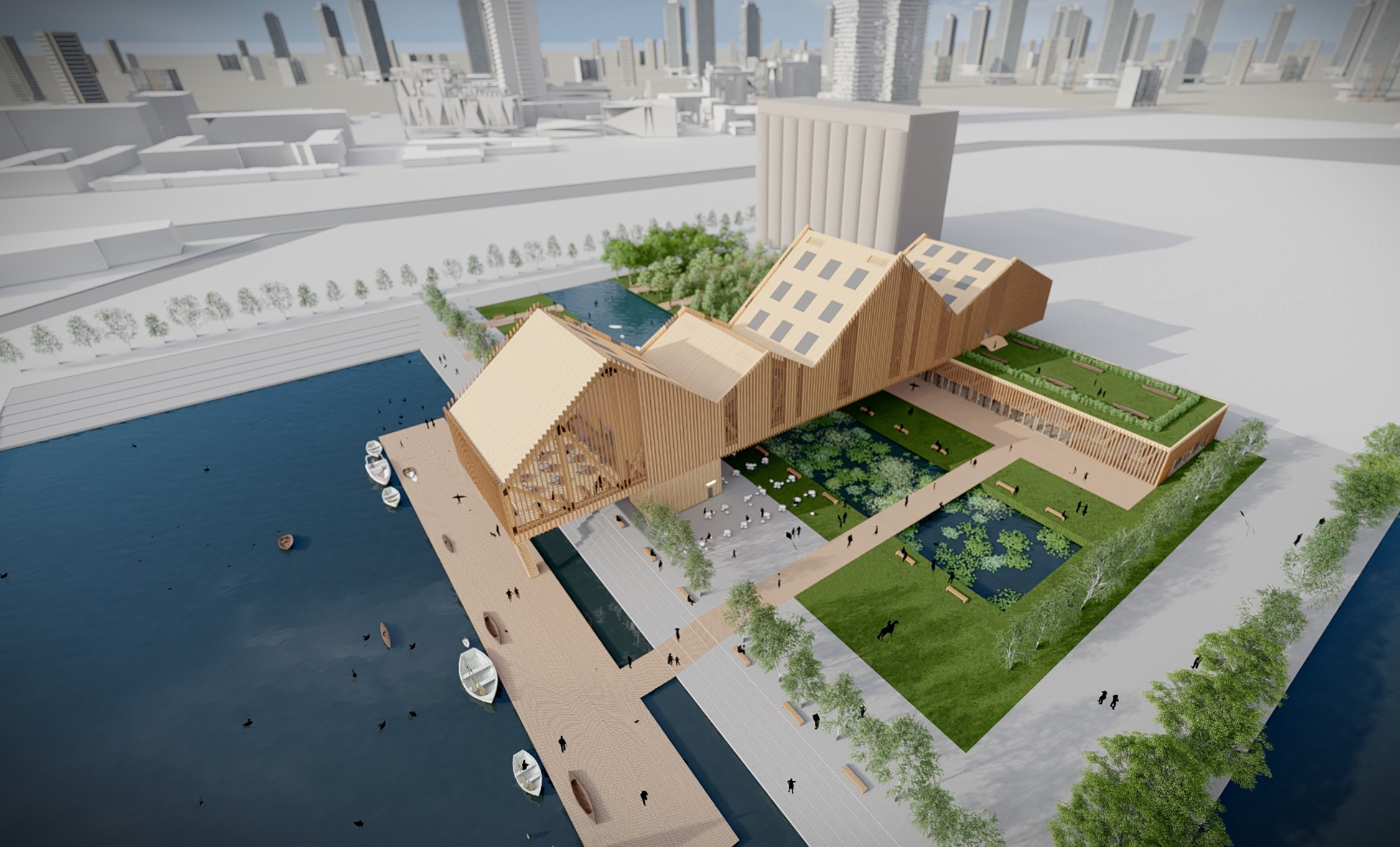

Nexus Square

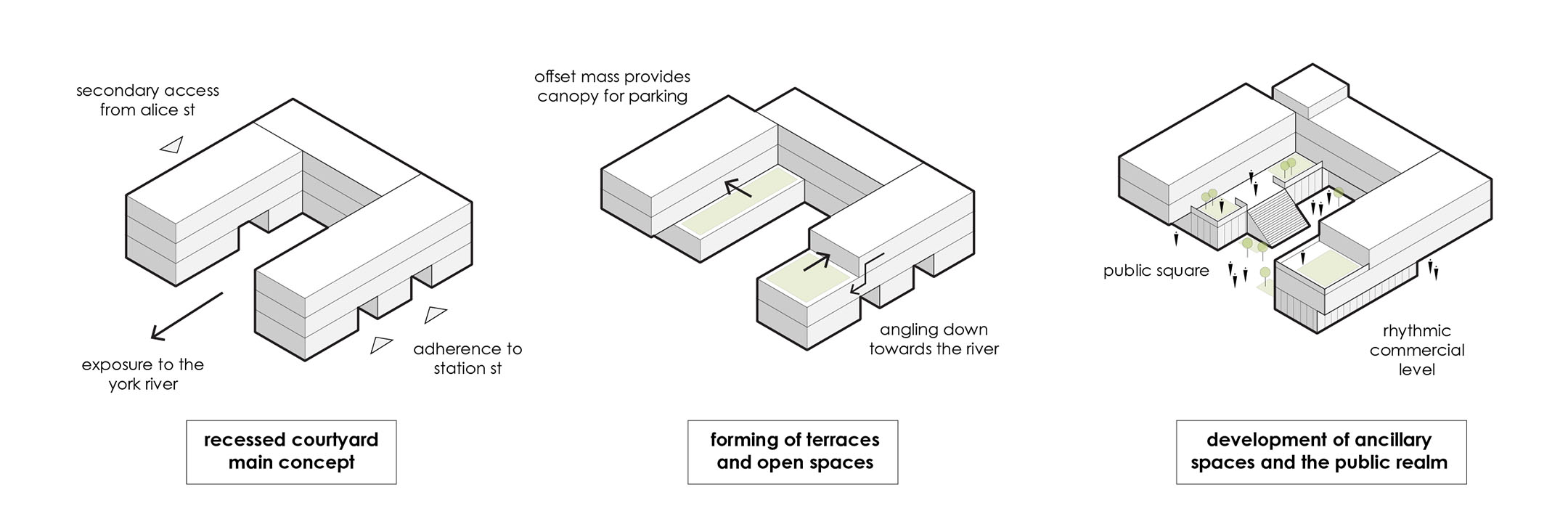

Located on 16 Station Street in Bancroft, Ontario, Nexus Square is a mixed-use development that provides careful consideration towards the York River. The ground floor serves as a public square, accommodating commercial and cultural uses while residential units are located on upper floors. The main focus of this development is on community-building and the gathering of townspeople. There is also an emphasis on creating a visual and physical connection to the river, hence the courtyard-style layout.

This project explores the recessed courtyard form in tandem with tectonics to deliver variability in public, private, and semi-private spaces. It establishes an architectural response to the lack of a "town square," breathing new life into the intimate town of Bancroft, Ontario.

Evergreen Community Housing

This project assigned students to design a housing complex for the small town of Bancroft, Ontario. The brief required students to study housing types, row houses & court houses, and apply modifications to suit the conditions of the site.

This design intends to enhance the transition from the public realm of Hastings street, to the private residential area through the use of landscaping and building orientation. The community space, located on the north east corner allowing the opportunity to open directly to the park, serves as flexible rental space and can host a local farmers market in the warmer seasons. This orientation allows pathways to the public park proposal, and provides a private green space for the residents of the complex.

This design intends to enhance the transition from the public realm of Hastings street, to the private residential area through the use of landscaping and building orientation. The community space, located on the north east corner allowing the opportunity to open directly to the park, serves as flexible rental space and can host a local farmers market in the warmer seasons. This orientation allows pathways to the public park proposal, and provides a private green space for the residents of the complex.

Madawaska Suites - Bancroft, Ontario

The Madawaska Suites is a ten-unit townhouse complex located at 1 Madawaska Street in Bancroft, Ontario. The complex houses four family and couple units, one live-work unit and one barrier-free unit. Additionally, the site also provides a communal building for all residents of Bancroft where they will be able to engage with one another by hosting arts and crafts sessions and tutorials, informal presentations and potluck meals. The site also contains a central outdoor space for residents within the complex to come together and share moments with each other in a space for relaxation where they can take in Bancroft’s exterior landscape.

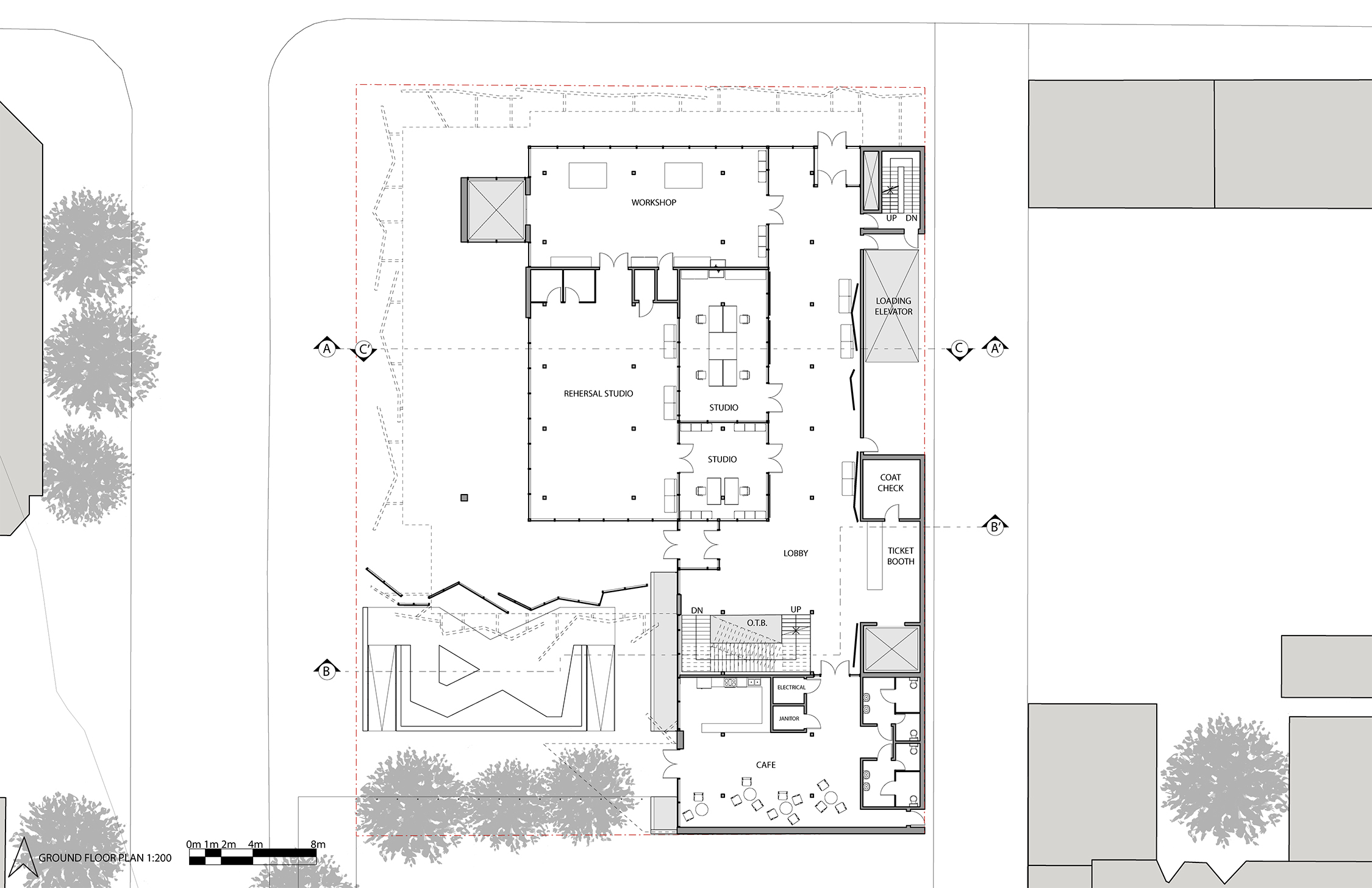

Tyler Chui

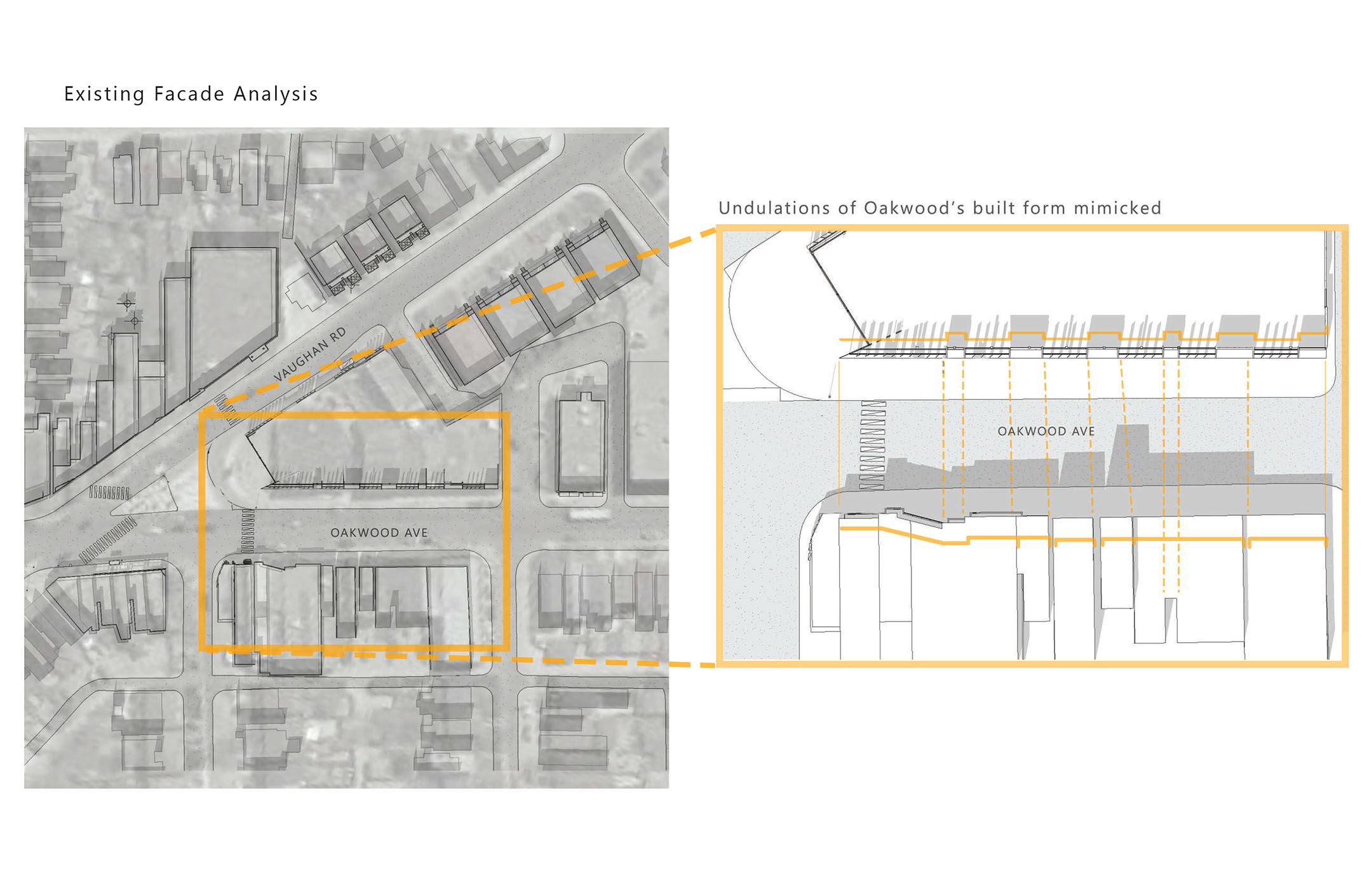

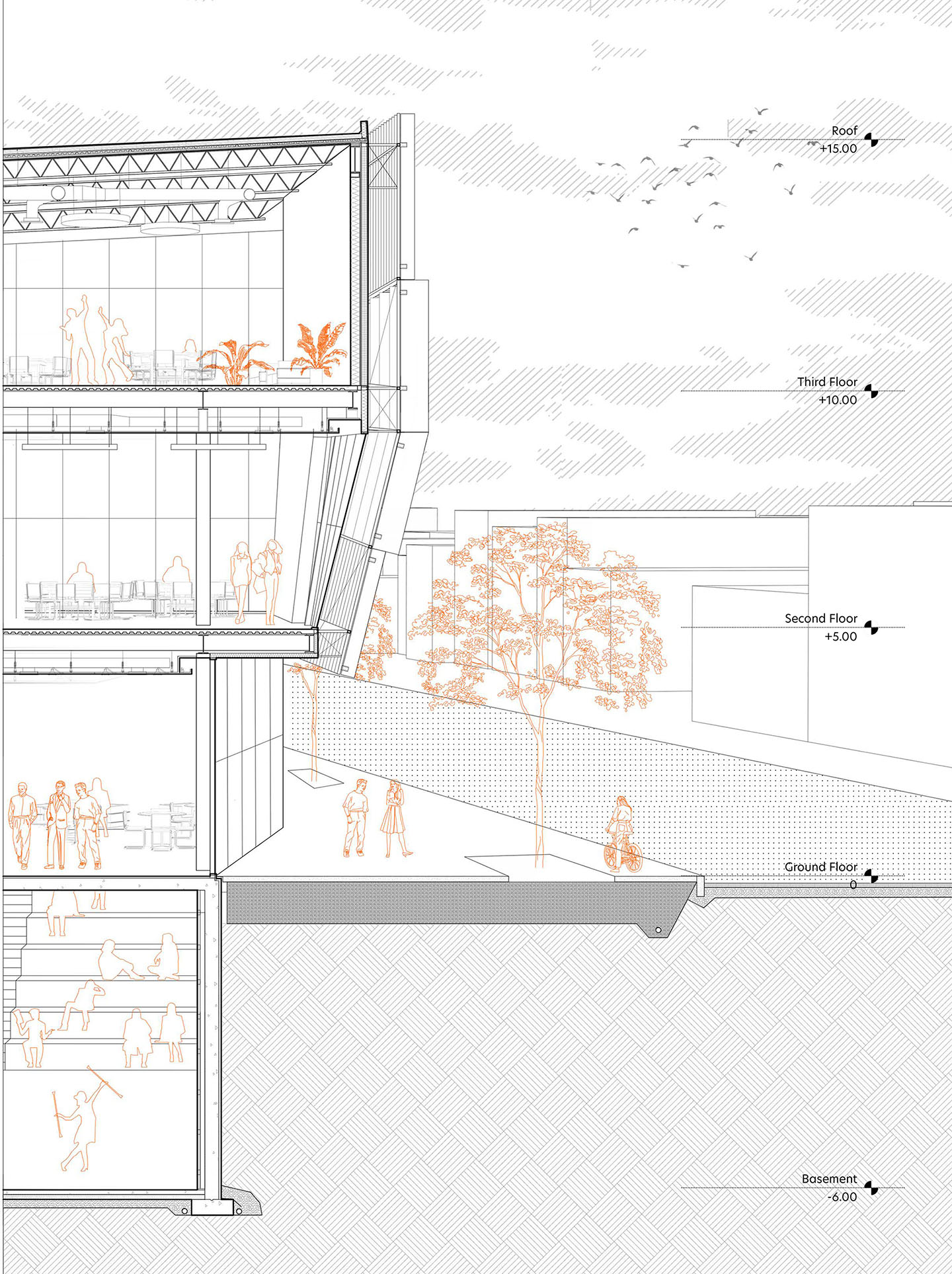

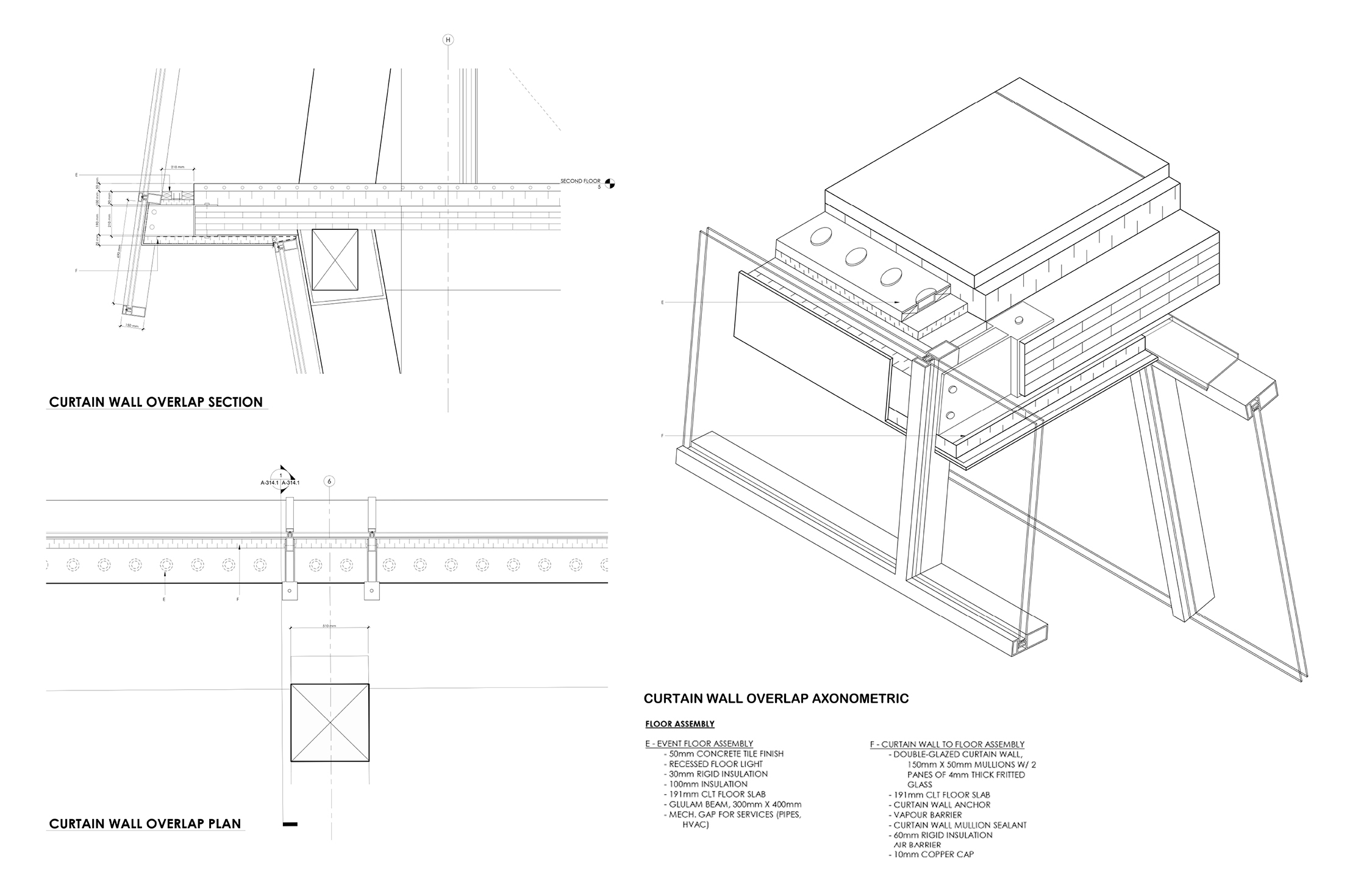

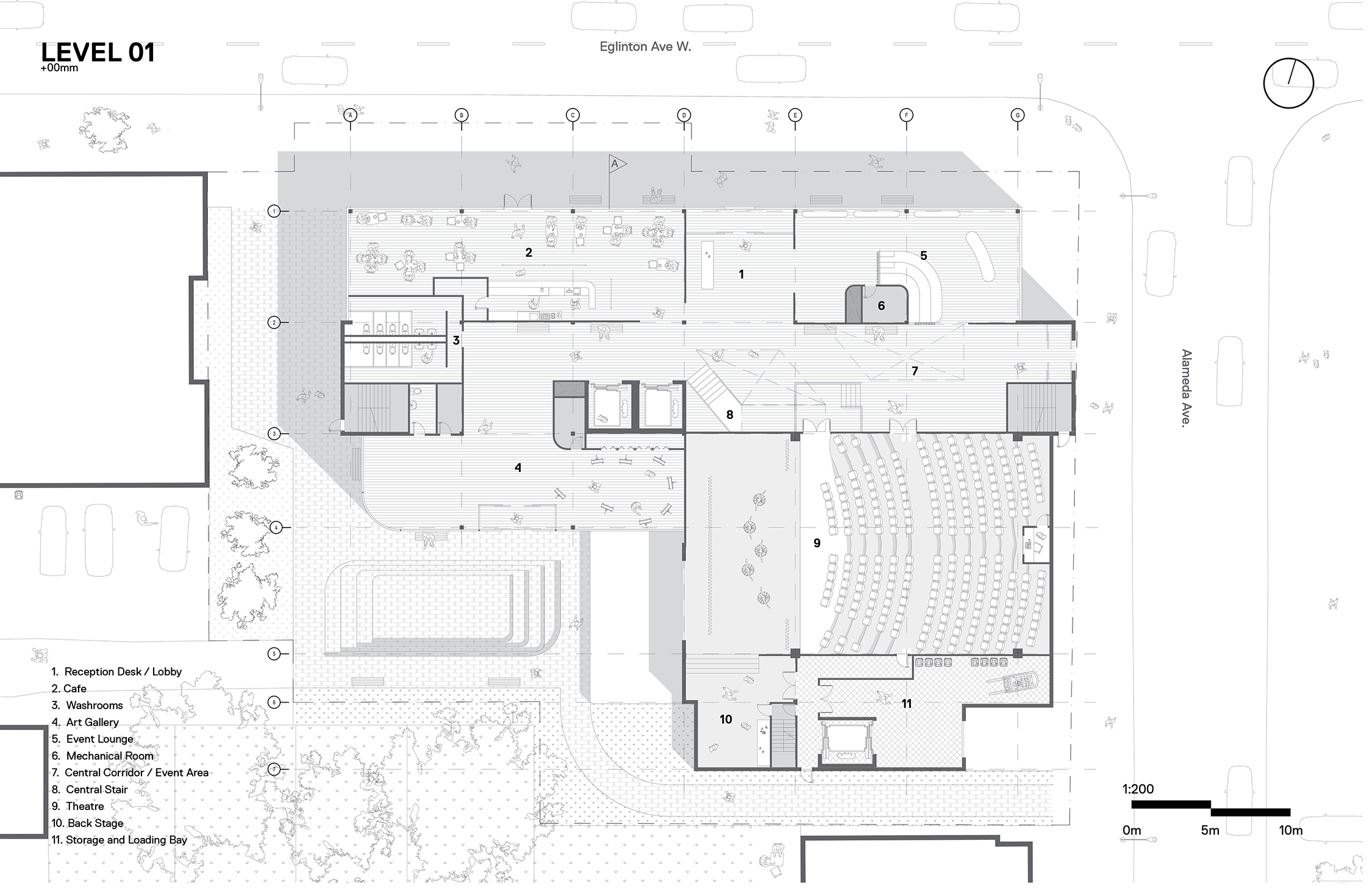

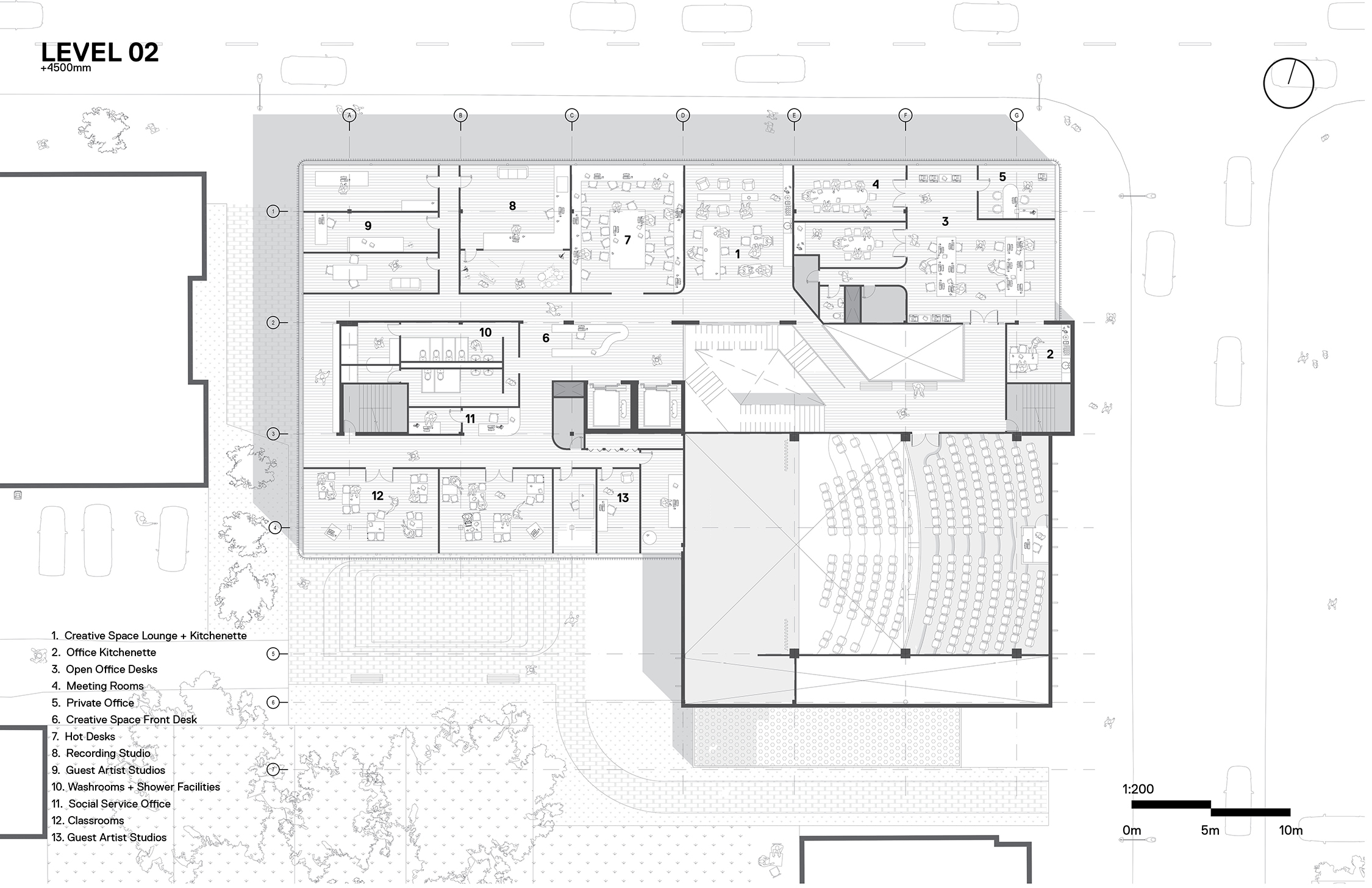

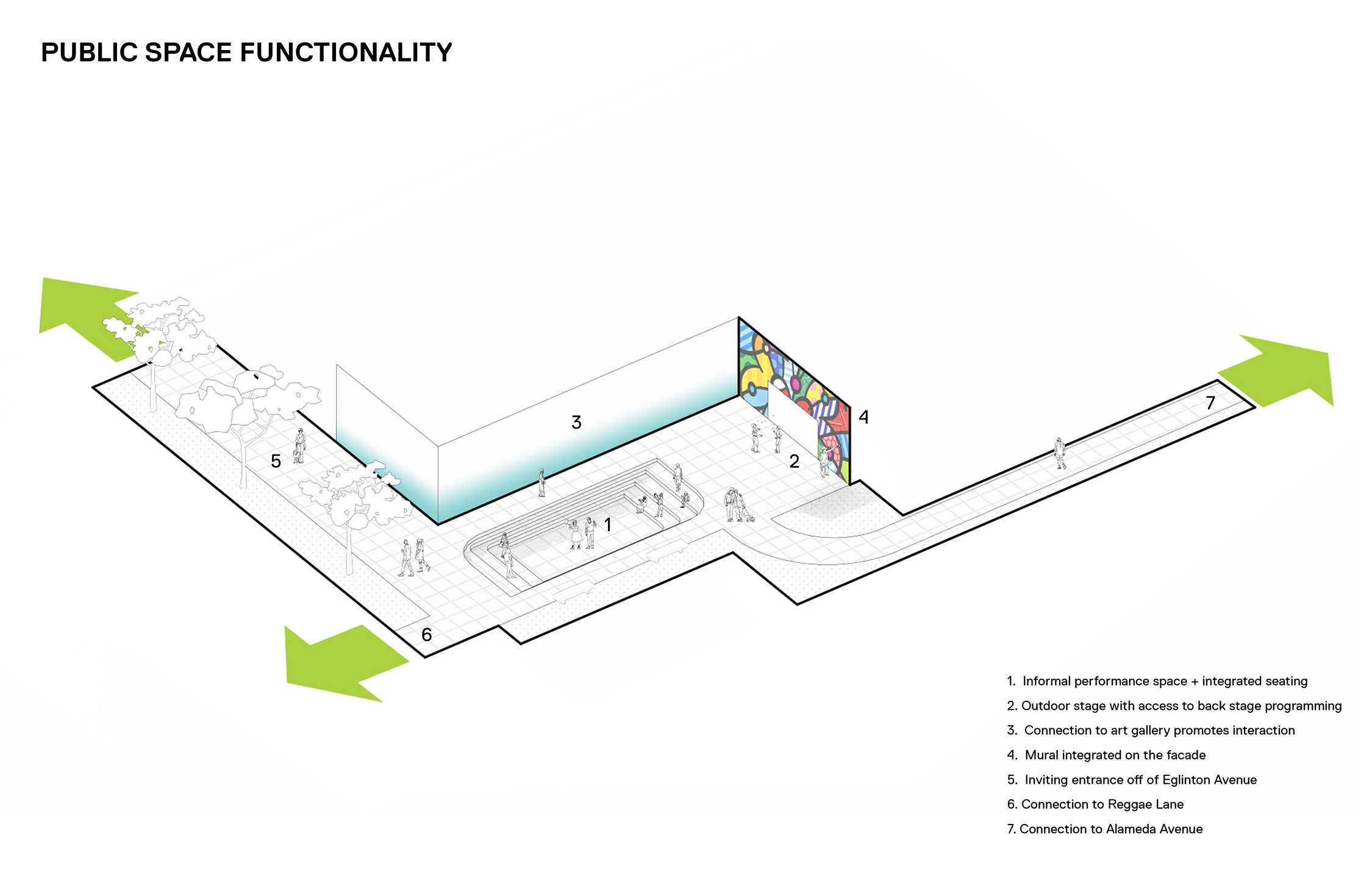

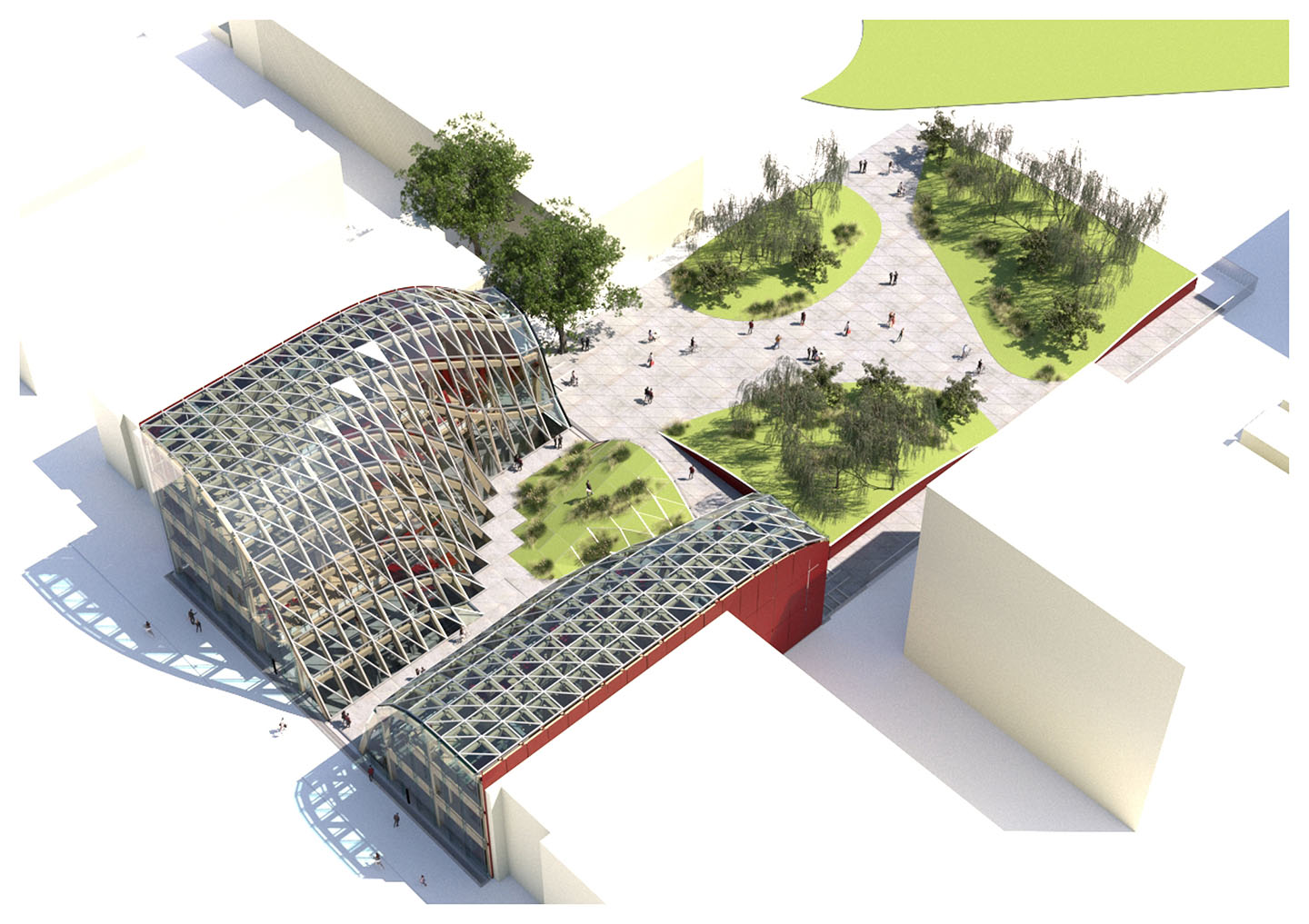

Nia Centre for the Arts

Nia Centre for the Arts

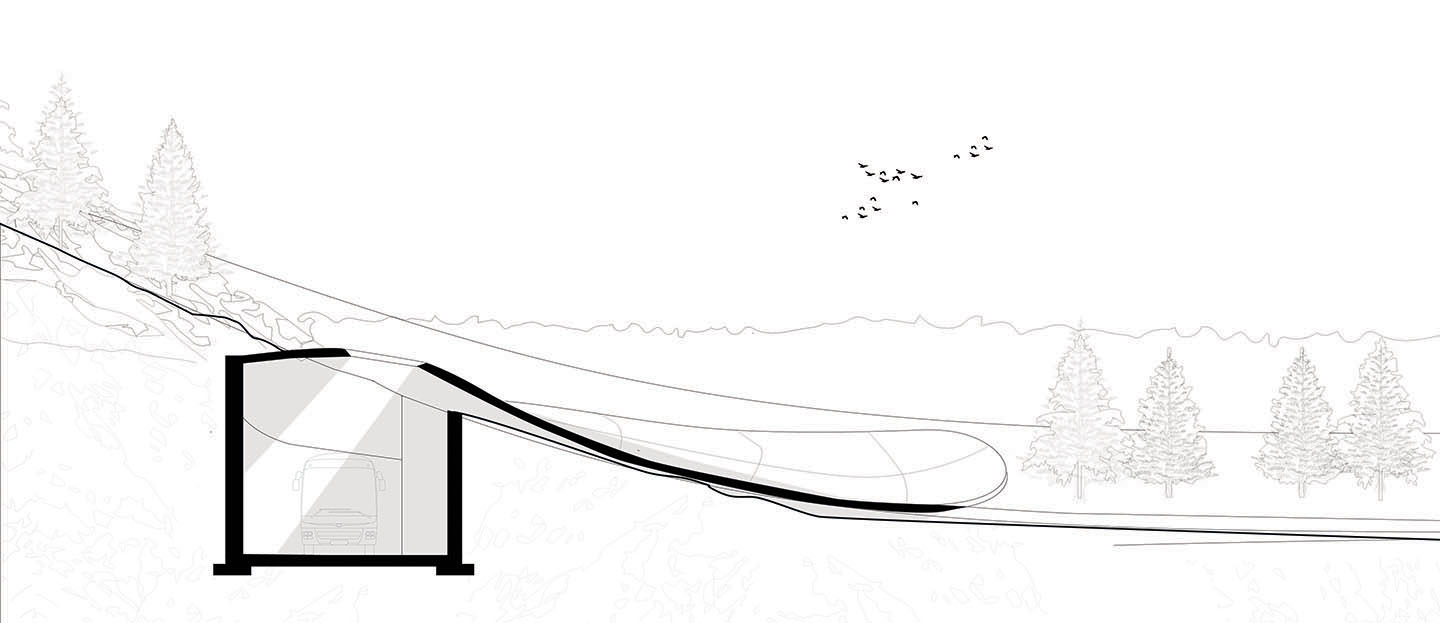

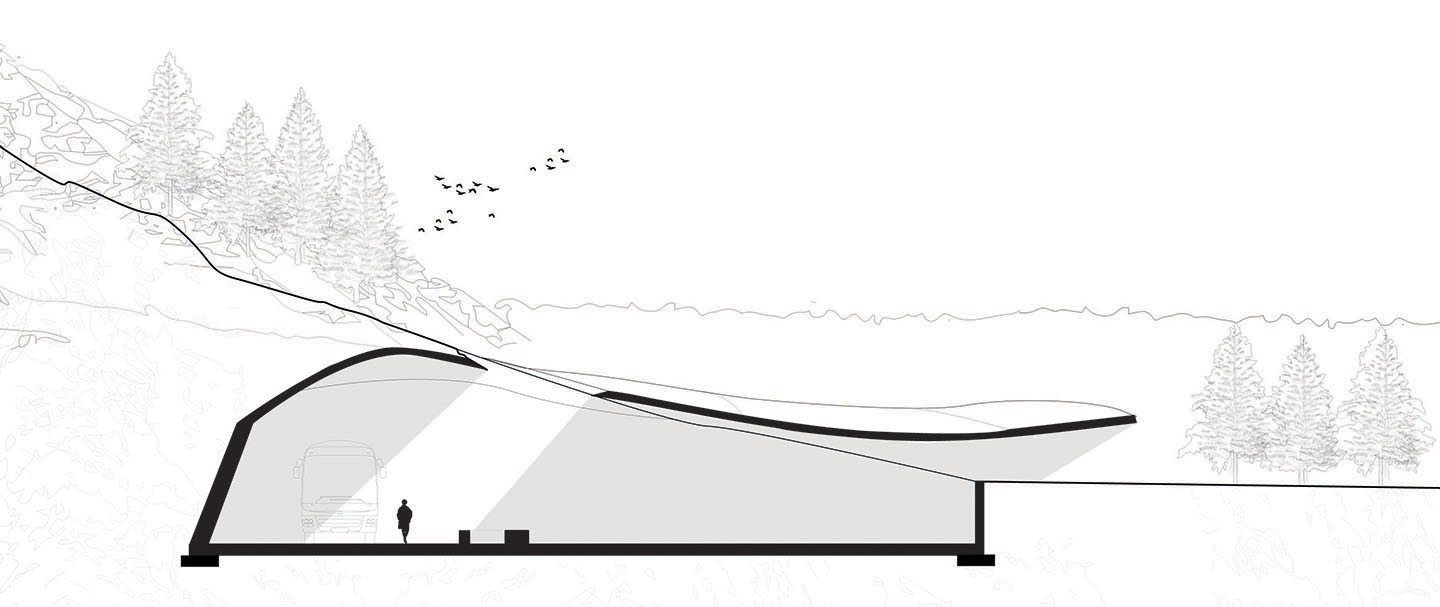

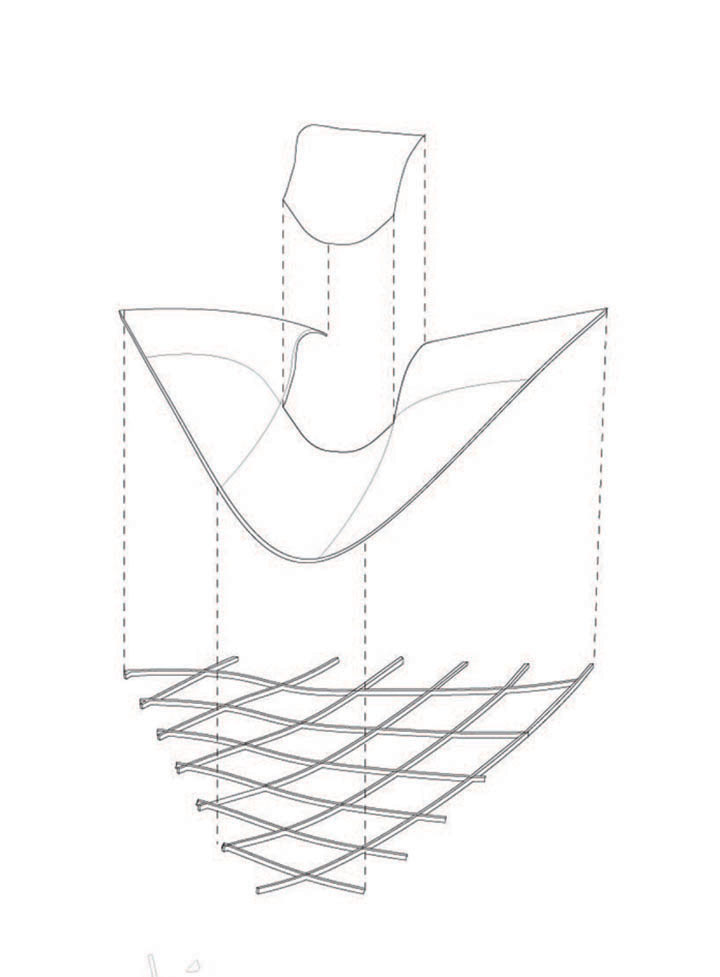

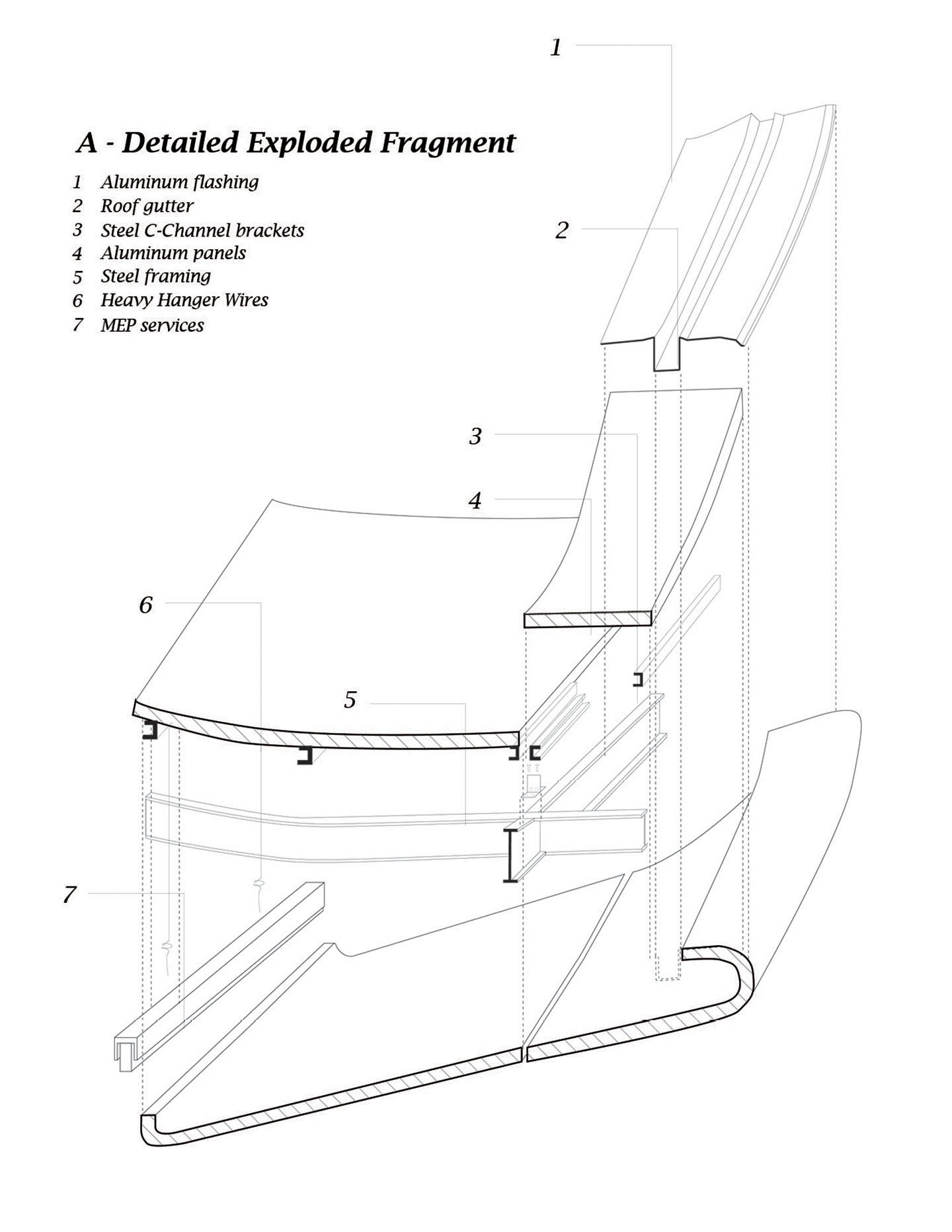

The ASC 520 studio integration was to design a performing Arts Centre for the company NIA located in Toronto’s Little Jamaica community. NIA is an organization for the appreciation of arts across the African Diaspora and is a hub for the community that showcases art and provides youth mentorship programs and workshops. To create a neighborhood hub, the proposal responds to the surrounding infrastructure with creating storefronts that undulate along the façade. This allows for variety and human scale when walking along Oakwood Ave. To activate the North intersection, the proposal’s roof reaches into the outdoor public space as a canopy with the sense of enclosure and security while still being outdoors.

Mathieu Howard

Nia Centre for the Arts

Nia Centre for the Arts

The proposal for the new NIA Centre For The Arts is centered around the idea of creating relationships between the community and the building by giving back something greater to the people of little Jamaica. The uninterrupted views from the interior program of the building to the street and vice-versa create a visual continuity between adjacent streets and the NIA Centre For The Arts through. The transparent ground floor contributes largely to this visual continuity, being clad entirely in glazing. The upper floors are clad in a sawtooth facade influenced by the street traffic and circulation on the site. The sawtooth facade is composed of glazing and aluminum panels overlaid with artwork. This gesture shows off artwork created by artists of the African diaspora and of the NIA Centre and creates a public exhibition of art. A reinforced relationship to the street created by the exposition of artwork on the facade fortifies the NIA Centre For The Arts as a datum for the neighborhood and as a symbol of identity for the community.

Ludovica Pasini

Nia Centre for the Arts

Nia Centre for the Arts

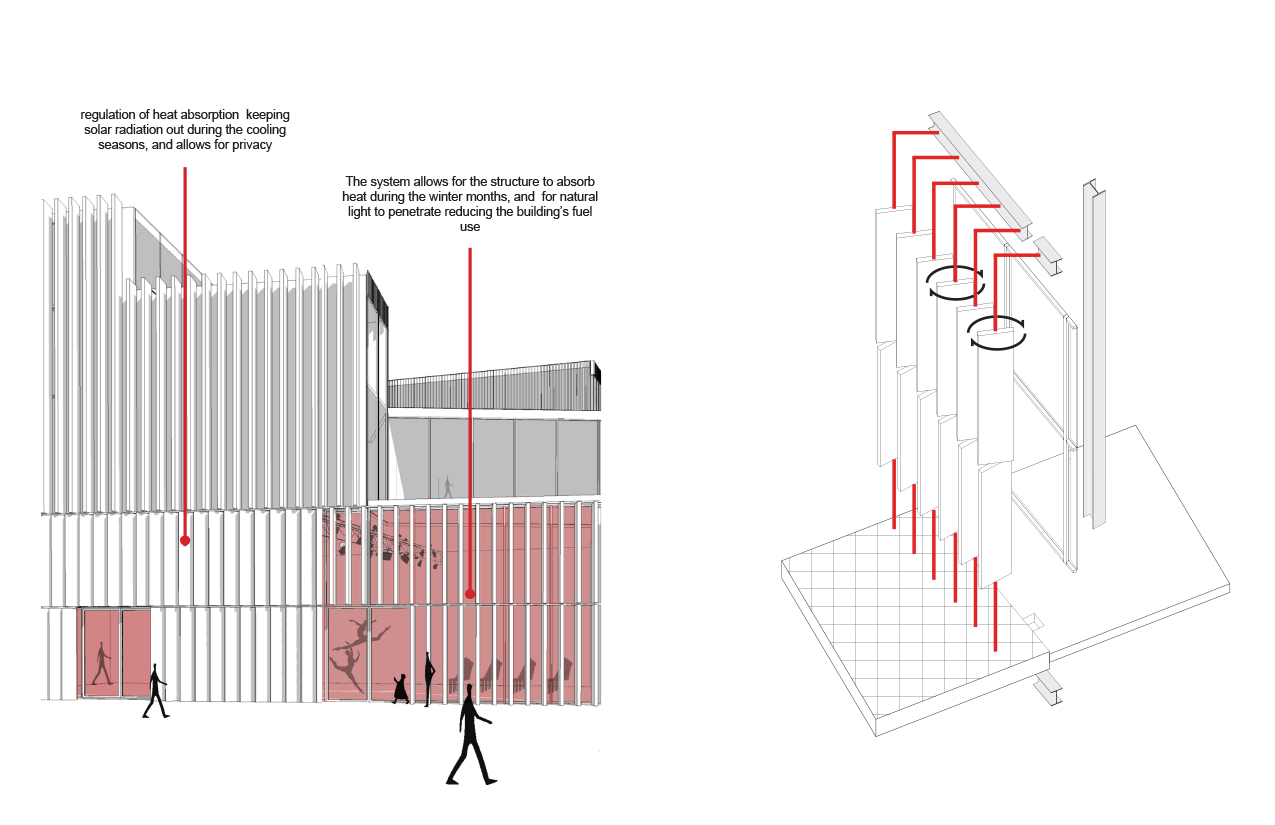

The proposed NIA center for the arts is situated in the heart of Little Jamaica, on Eglinton Ave W. The exercise aims to bring students to the acknowledgment of how context and culture are the key driving forces of a design. In consideration of this the Nia Center wants to act as a cultural hub for the black artist community, by performing as a meeting point to the adjacent school, library, park, while the front facade of the building will interact with pedestrians on the main street of Eglinton Ave W. The appearance of the building will mimic the verticality conveyed by the neighborhood, with the use of vertical rotating wood composite panels, and aims to evoke curiosity through space and form mutation, resulting in the beginning of a cultural attitude.

Adneth Marie Kaze

Nia Centre for the Arts

Nia Centre for the Arts

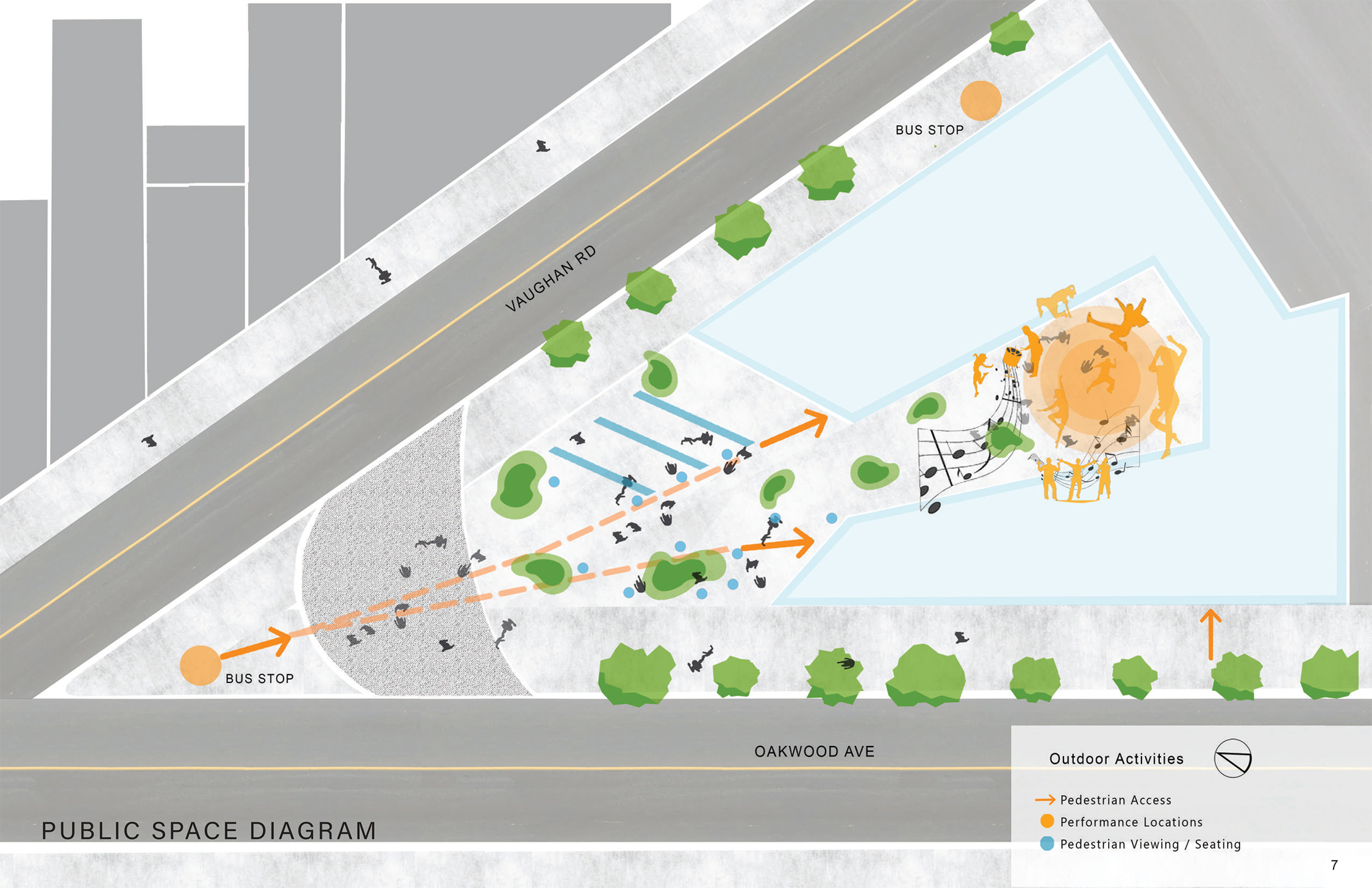

The Nia Centre is a Toronto-based not-for-profit organization that supports, showcases, and promotes an appreciation of arts from across the African Diaspora. The vision for the Nia Centre is to create a safe space for young black creatives to express their creativity freely. There is a need for a gathering space free from the mainstream stereotypes and marginalization that permeate every other societal space.

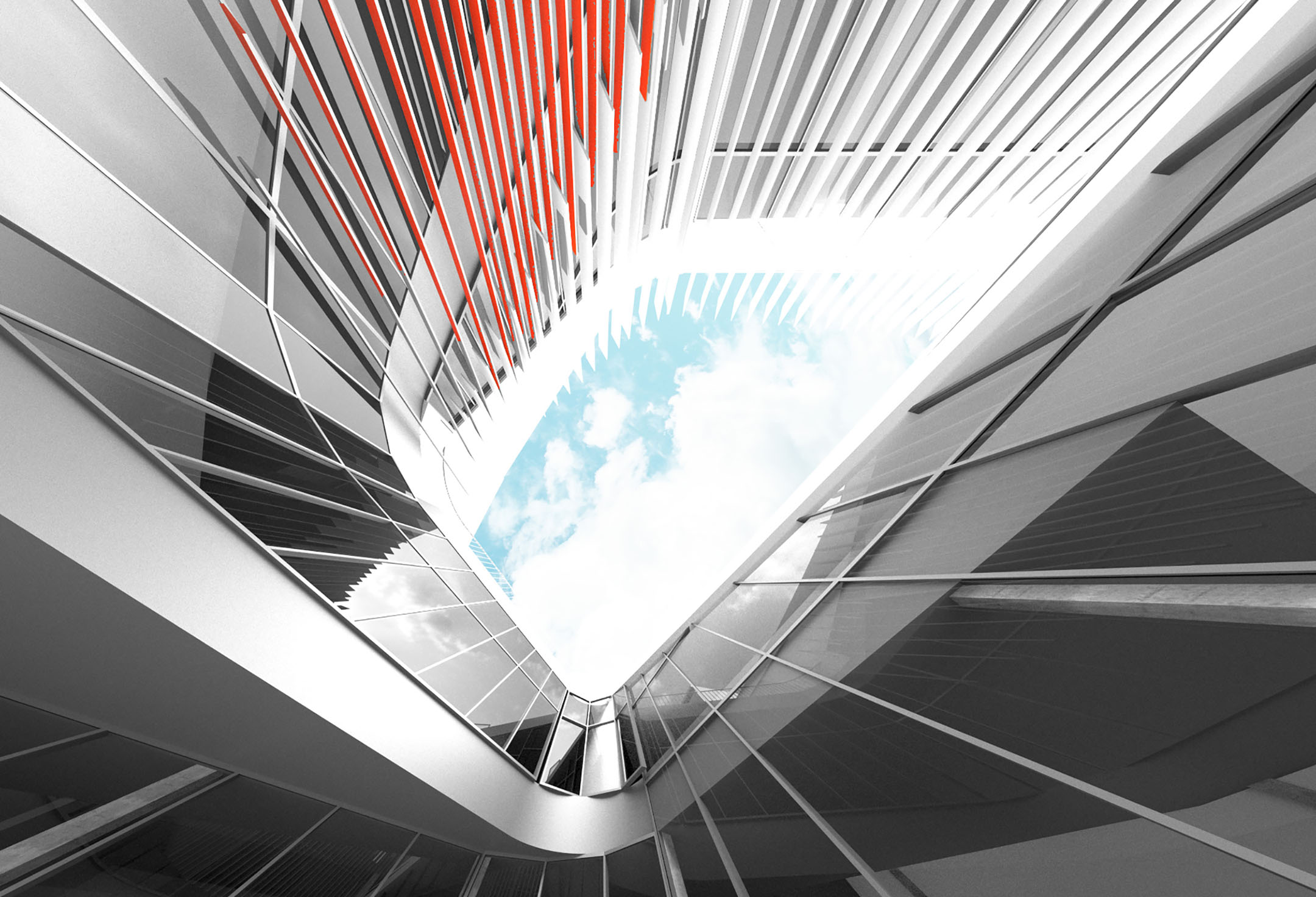

The concept revolves around the idea that the black experience is not a monolith and includes multiple facets interacting together to create a culture. The design strategies follow the ideas of diversity and connectivity as it includes a central courtyard connecting to the three levels and all the program of the building. The program is organized in a way that maximizes interconnecting floor space and open spaces. By scattering the program all over the building, it allows for users to be exposed to different activities taken part in the building. This sense of diversity within this community allows the building to become a whole.

The Nia Center Is more than a Performing Arts Centre, it becomes a tool to strengthen the sense of community within Little Jamaica. For this project, I chose to build on the Oakwood Avenue and Vaughan Road “Five Points” Intersection, representing, by itself a focal point connecting to the rest of the neighbourhood.

The concept revolves around the idea that the black experience is not a monolith and includes multiple facets interacting together to create a culture. The design strategies follow the ideas of diversity and connectivity as it includes a central courtyard connecting to the three levels and all the program of the building. The program is organized in a way that maximizes interconnecting floor space and open spaces. By scattering the program all over the building, it allows for users to be exposed to different activities taken part in the building. This sense of diversity within this community allows the building to become a whole.

The Nia Center Is more than a Performing Arts Centre, it becomes a tool to strengthen the sense of community within Little Jamaica. For this project, I chose to build on the Oakwood Avenue and Vaughan Road “Five Points” Intersection, representing, by itself a focal point connecting to the rest of the neighbourhood.

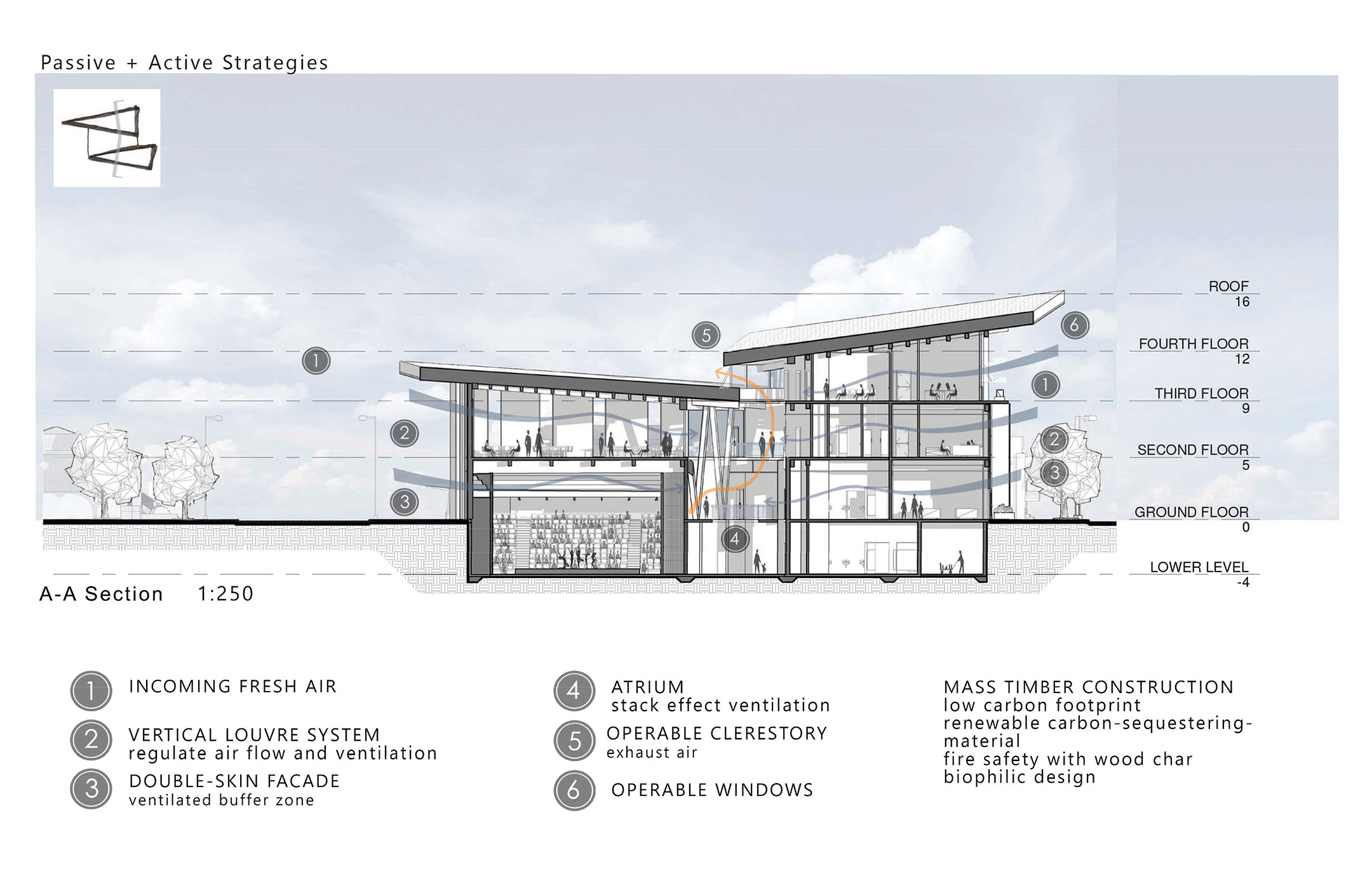

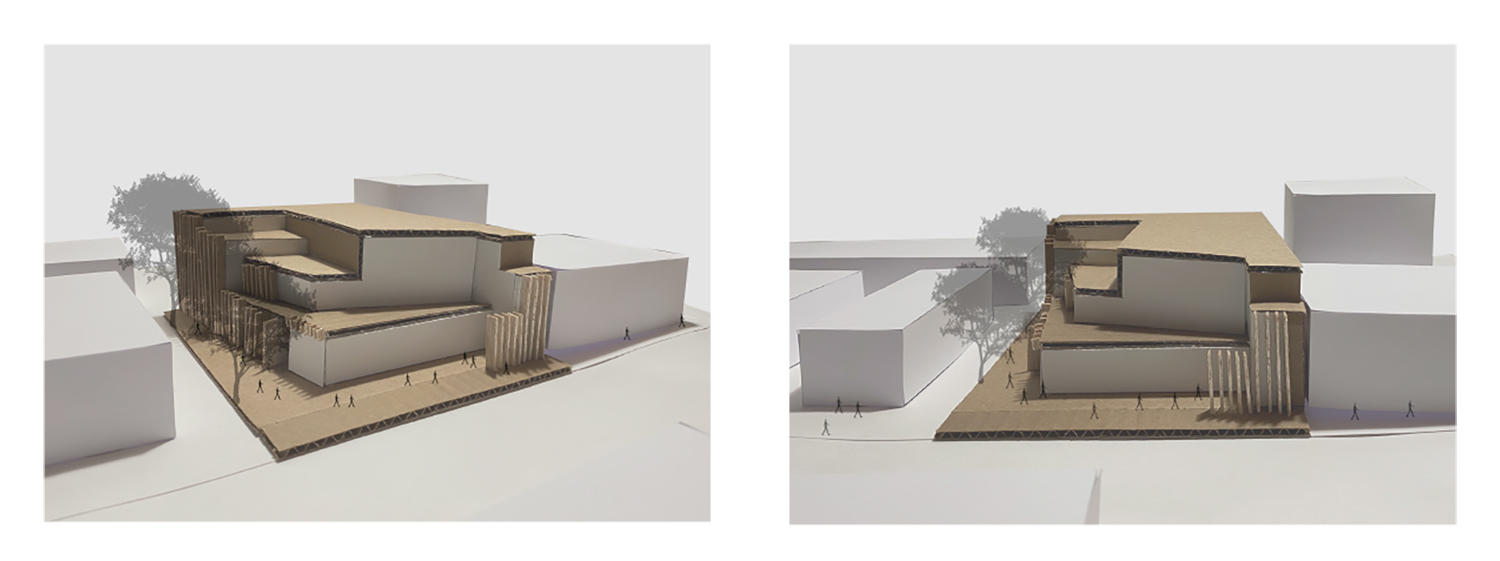

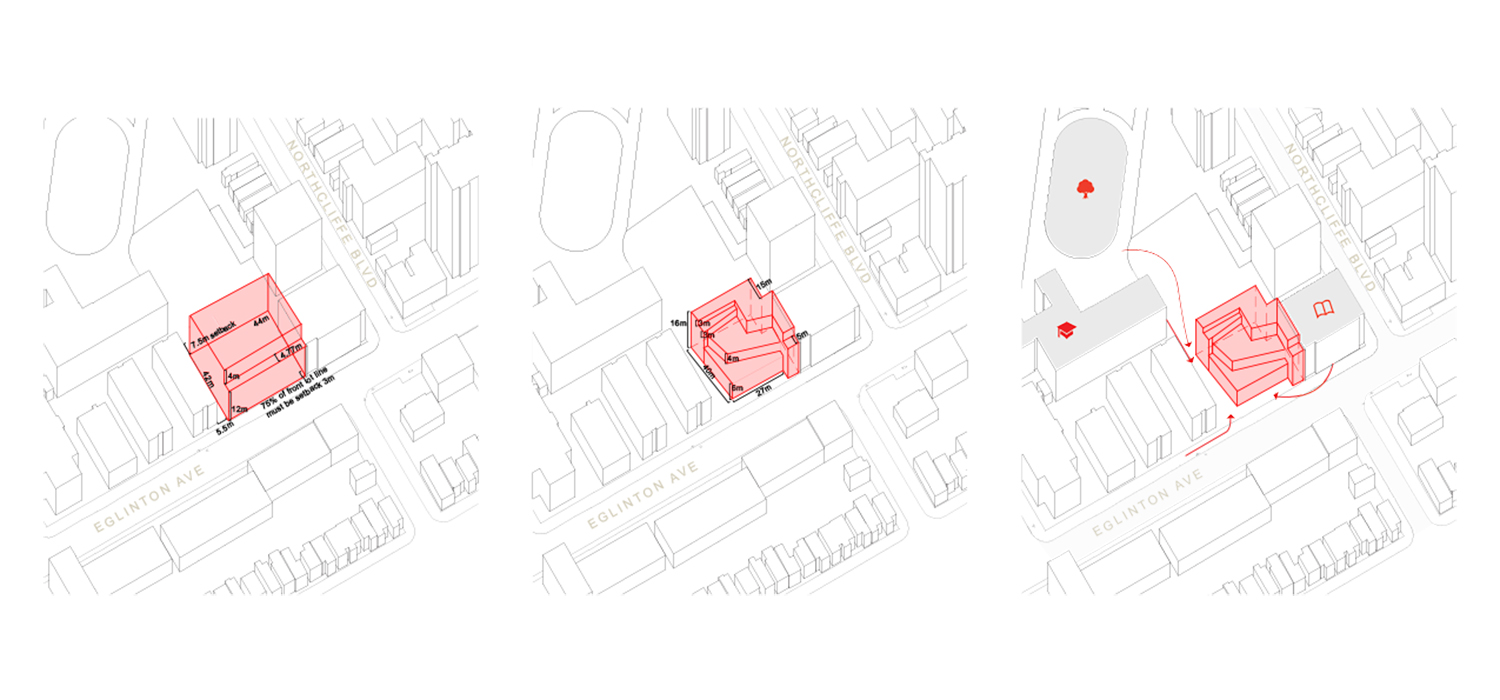

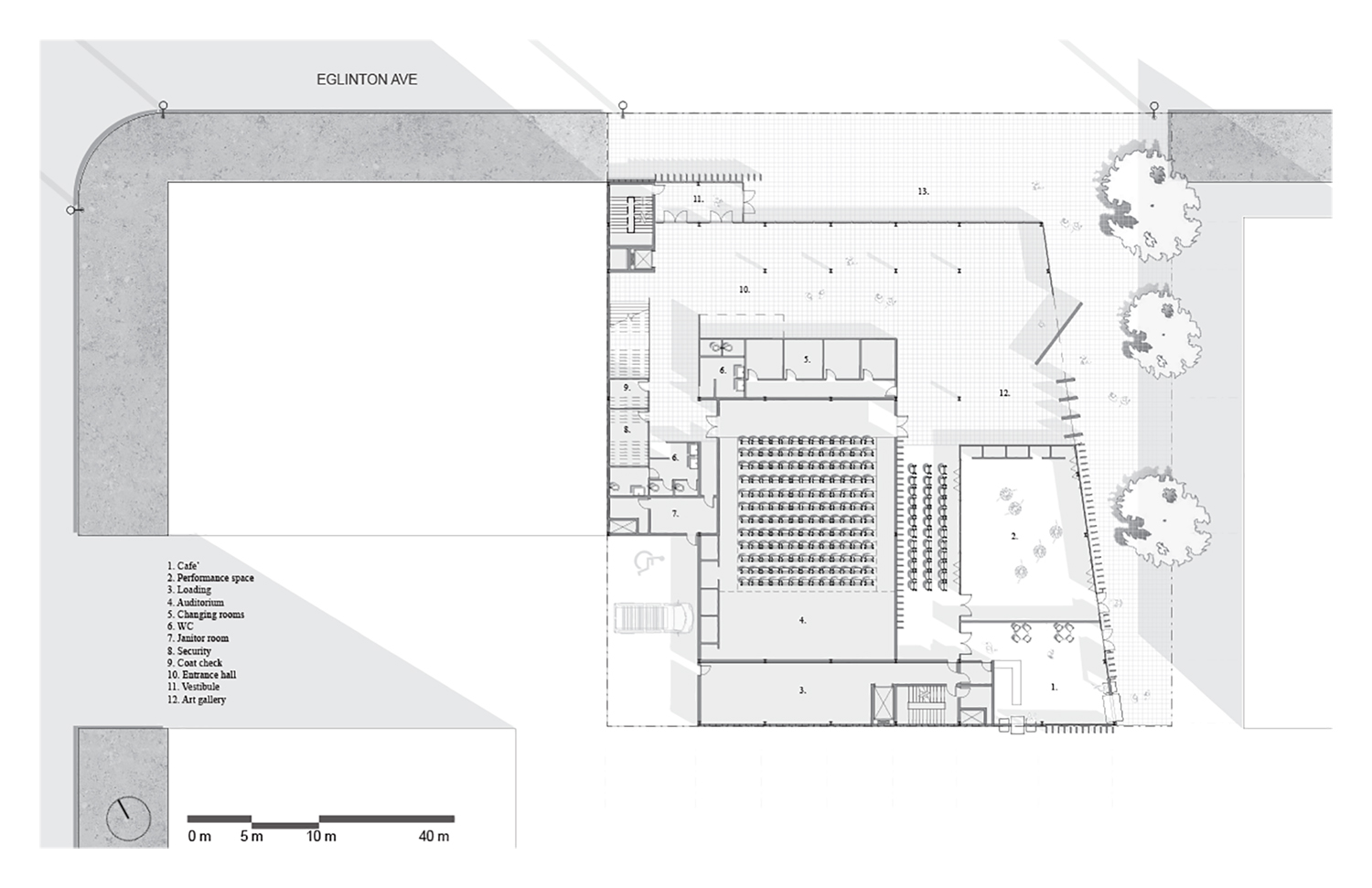

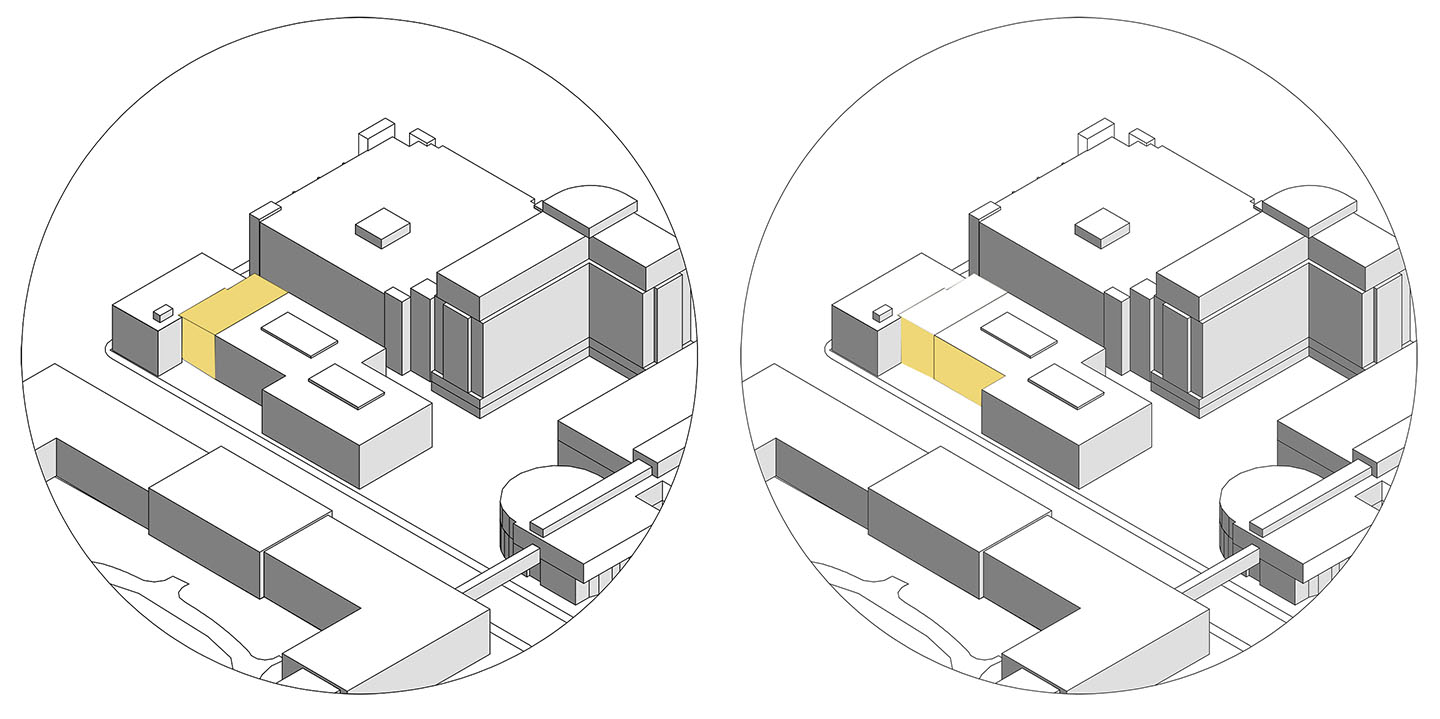

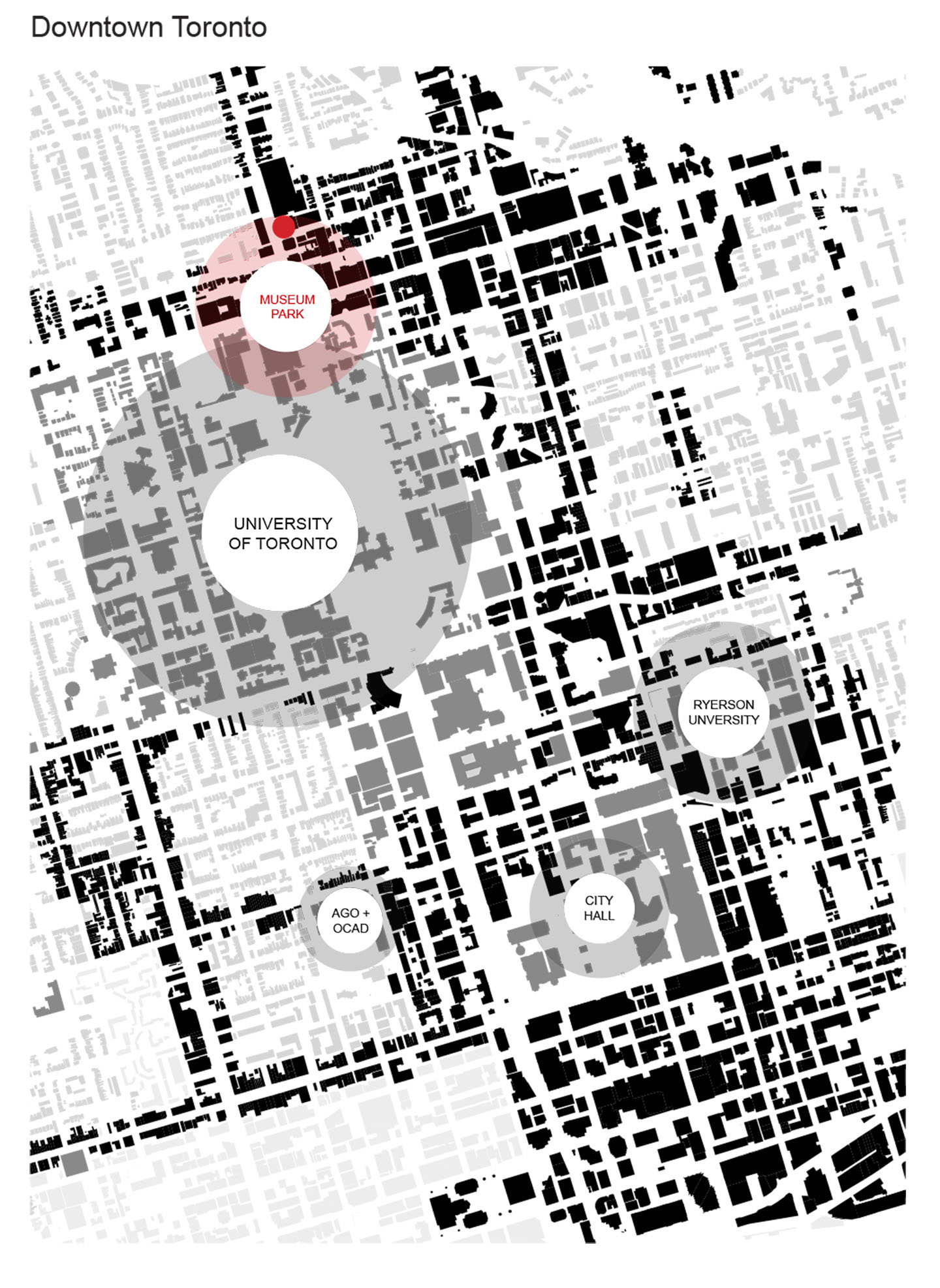

Nia Centre for the Arts - Integration and Innovation Synthesis

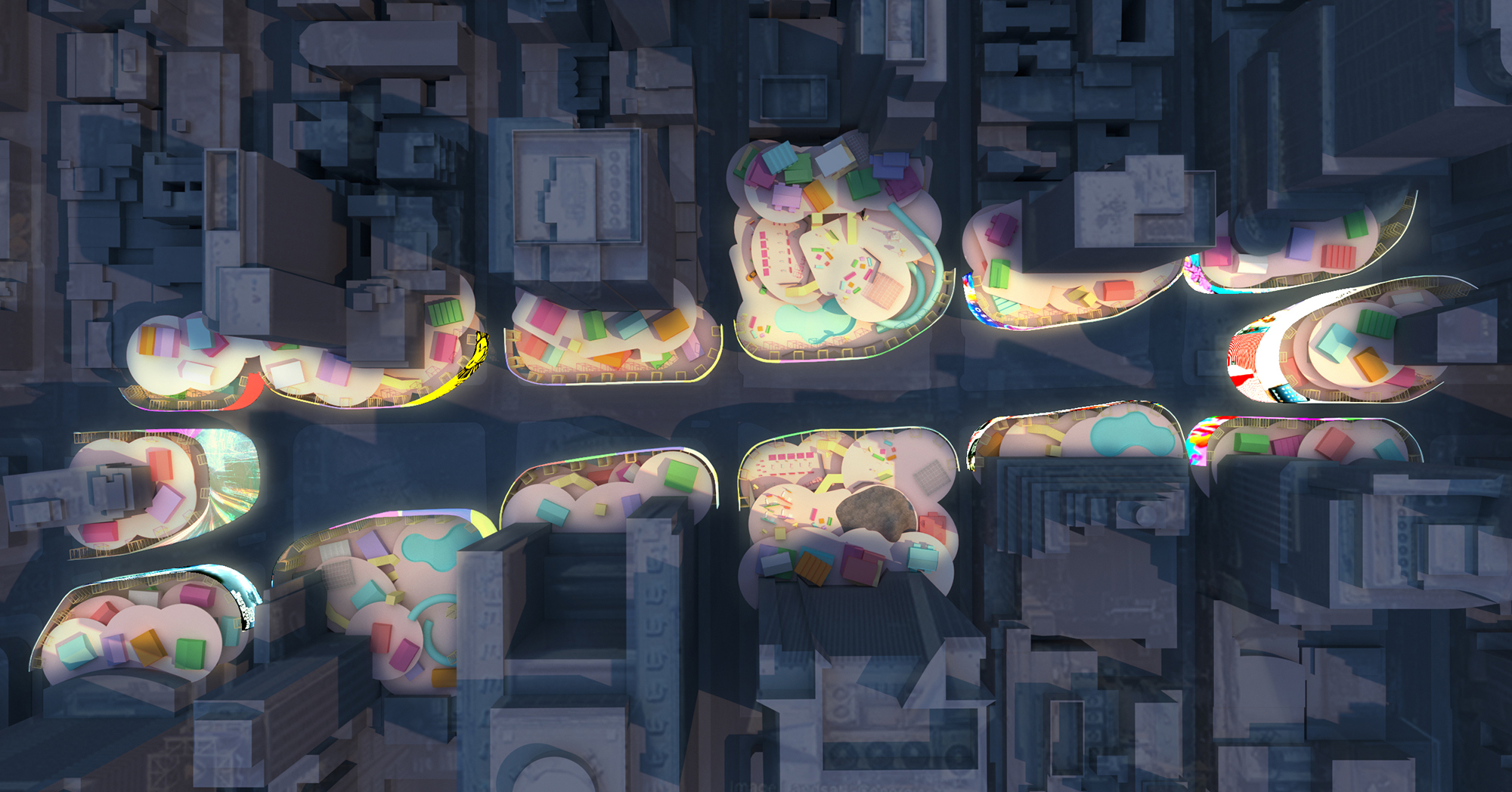

The NIA Centre for the Arts is an arts focused community centre specifically dedicated to the African Canadian community. They hold art courses, gallery shows, lectures, and performances. The project takes place in Little Jamaica in Toronto. The neighbourhood is mainly residential and low-rise. At the beginning of the year, we investigated 5 different sites in the neighbourhood. The chosen site at the intersection of Oakwood Ave and Vaughan Rd has very clear and long views and has proximity to educational buildings. The site is also known as the ‘5 points’ due to its location at the convergence of several roads in the area. The Little Jamaica neighbourhood is becoming gentrified however there are many murals all over the neighbourhood which solidify the arts as a unifying factor in the culture, which makes an arts focused building more important to the community.

The building is split into three public portions on the site and each has a kind of destination pertaining to the uses of the building. In the middle it is outdoors while on either side there are indoor paths parallel. This configuration on the site connects the public outdoor spaces to the public indoor spaces and organizes the program and activities. The two forms wrap around the public space in this way. The design pulls back from the front of the site and angles inward to draw the public in and lead people to the outdoor destination which becomes connected to the indoor activities.

NIA Centre for the Arts

The NIA Centre for the arts aims to integrate the unique culture and artistic expression of the surrounding little Jamaica neighborhood into a building which becomes a beacon within the community. The centre supports the existing local artistic community while fostering the next generation of creative minds. The building aims to become a place that community members can take advantage of throughout their daily lives.

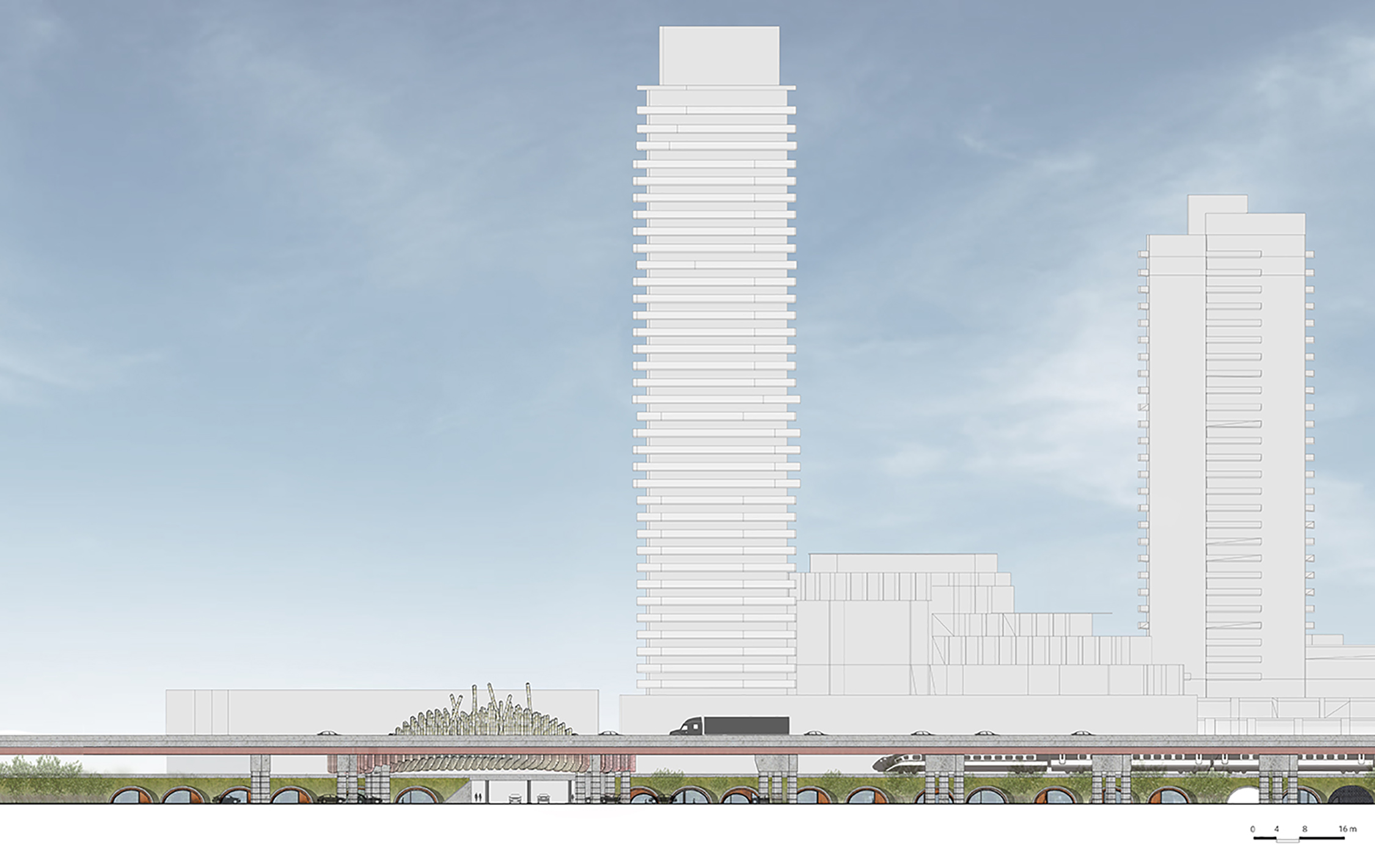

Phase 02 DD: Integration and Innovation Synthesis - Rise

Based on previous site research, we found that the black and African diaspora could greatly benefit from a more impactful community hub within Little Jamaica, binding the streetscape of Eglinton with the previously existing greenspace located behind the site.

Our design performs as a gateway between the streetscape of Eglinton Ave W and the greenspace that lies behind the site, reintroducing the pre existing greenspace to the public realm. The building rises upwards at the east and west edges of the site, allowing a valley to form in the middle, creating a visual connection between occupants of the building, the pedestrians passing through, and the busy Eglinton streetscape. The structures have been divided based on use, resulting in a public and private tower on either side of the site, connected by two storeys below grade that act as a collaborative, educational space.

Phase 02 C: Integration and Innovation Synthesis

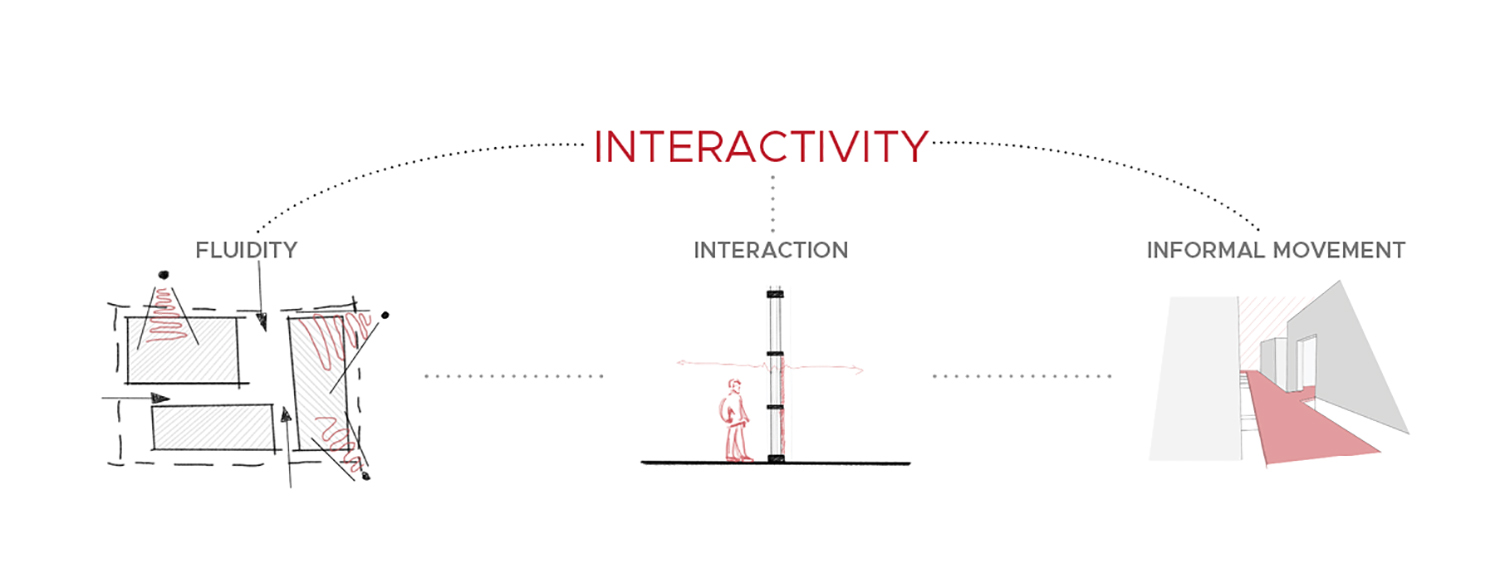

- Interactivity

The intent of this design seeks to actively connect the bustle of the exterior environment to the creative activities of interior space, ultimately bridging the gap between NIA’s inner community and Toronto at large. Specifically, by creating an ensemble through compartmentalization of program into three structurally independent entities, an informal interior streetscape is established. This streetscape allows users to circulate about the perimeter of the building, fostering a direct connection with the exterior streetscape below. Further, an atmosphere of lightness is employed at large through a double-skin envelope condition. Large areas of diffuse glazing and operable glazing elements serve to allow for natural light and fresh air to permeate into various modular interior spaces within the ensemble, ultimately augmenting user experience.

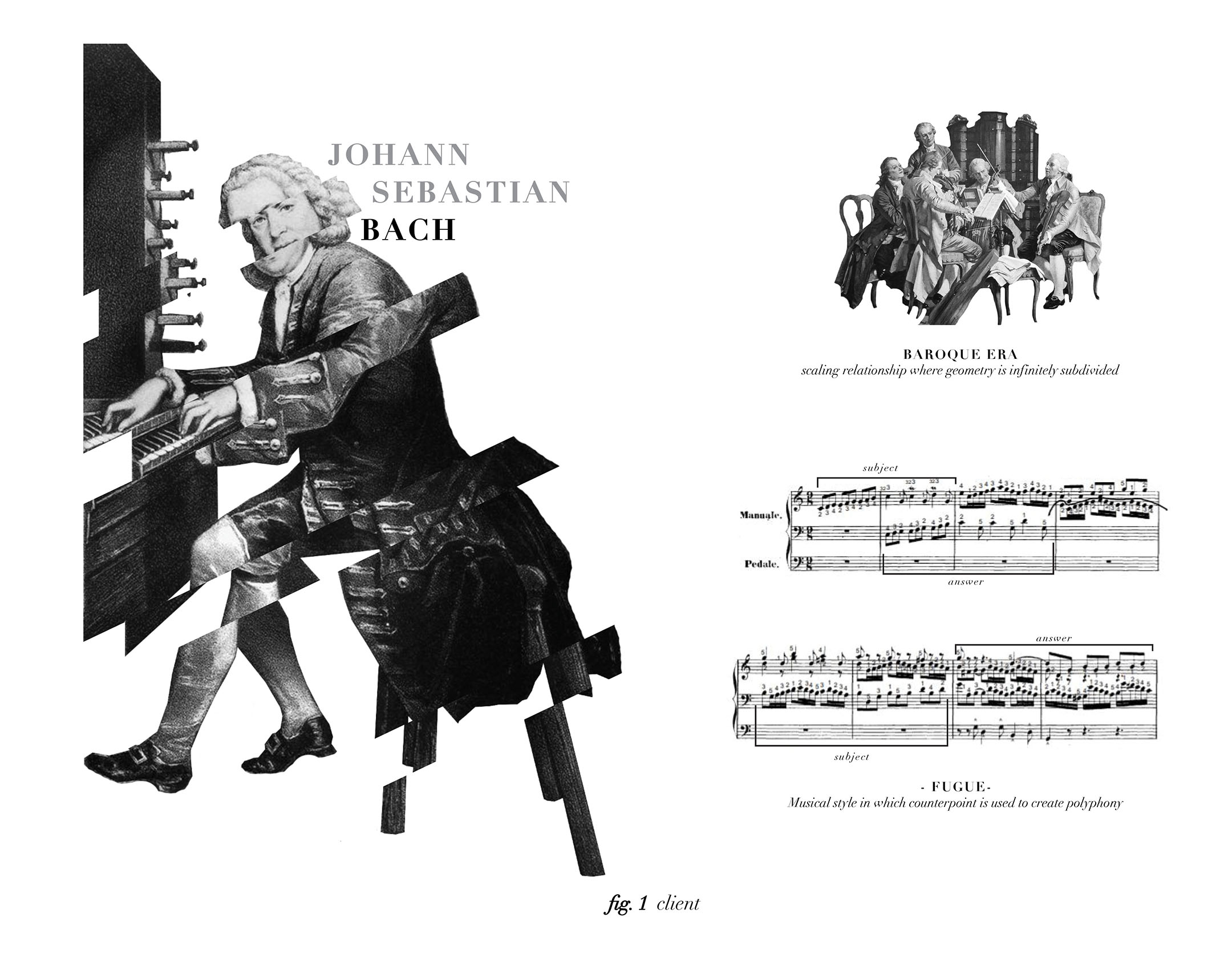

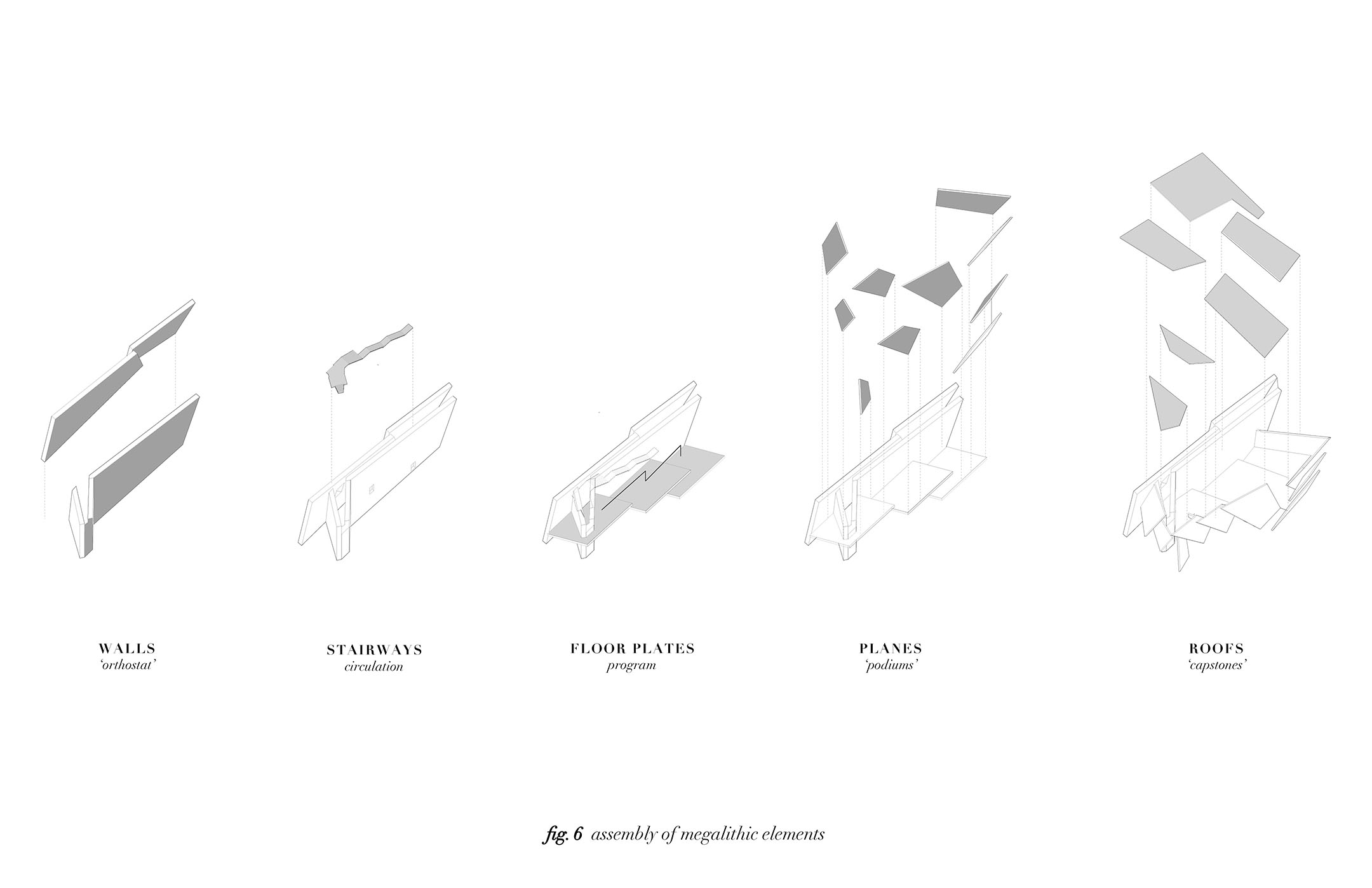

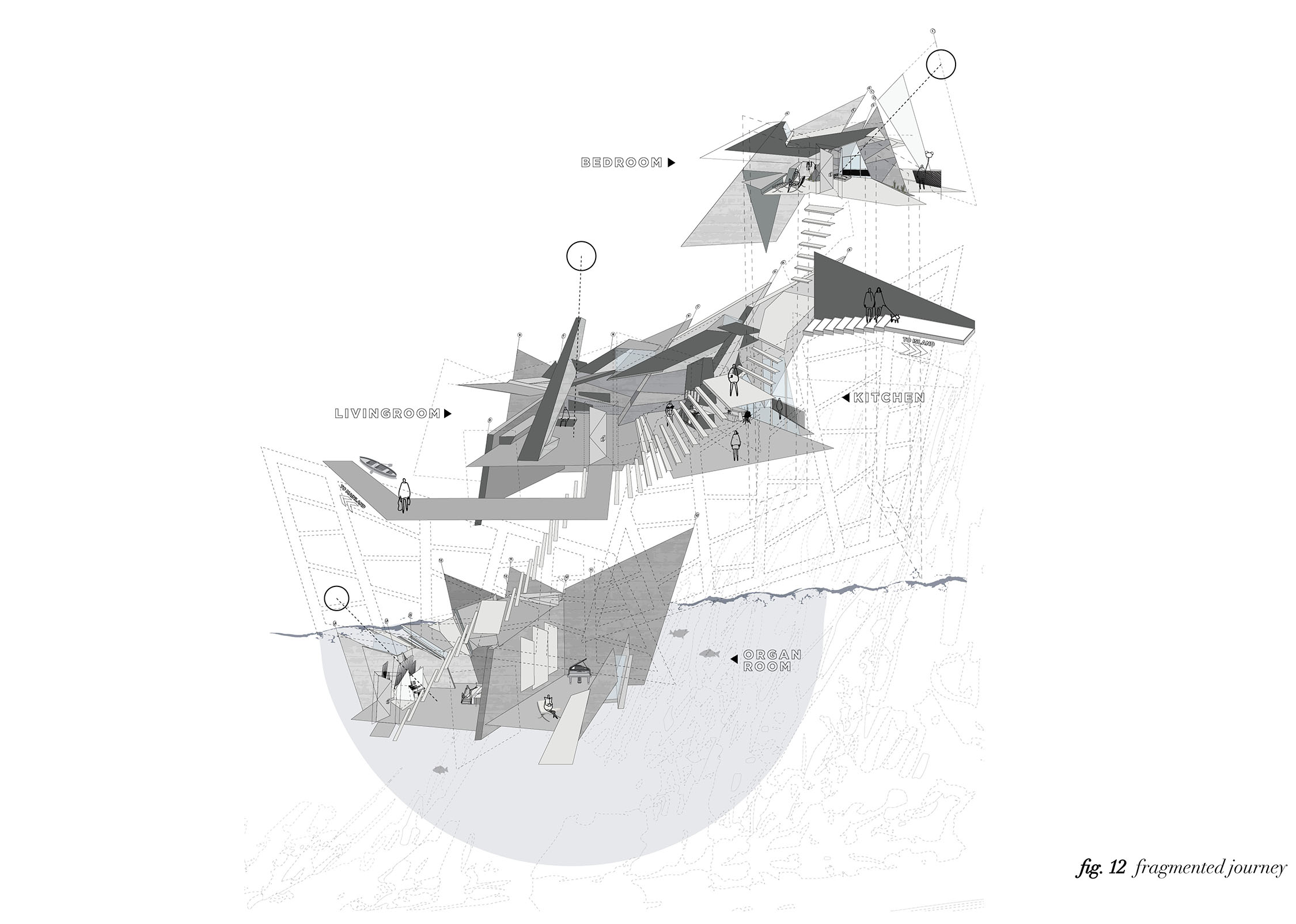

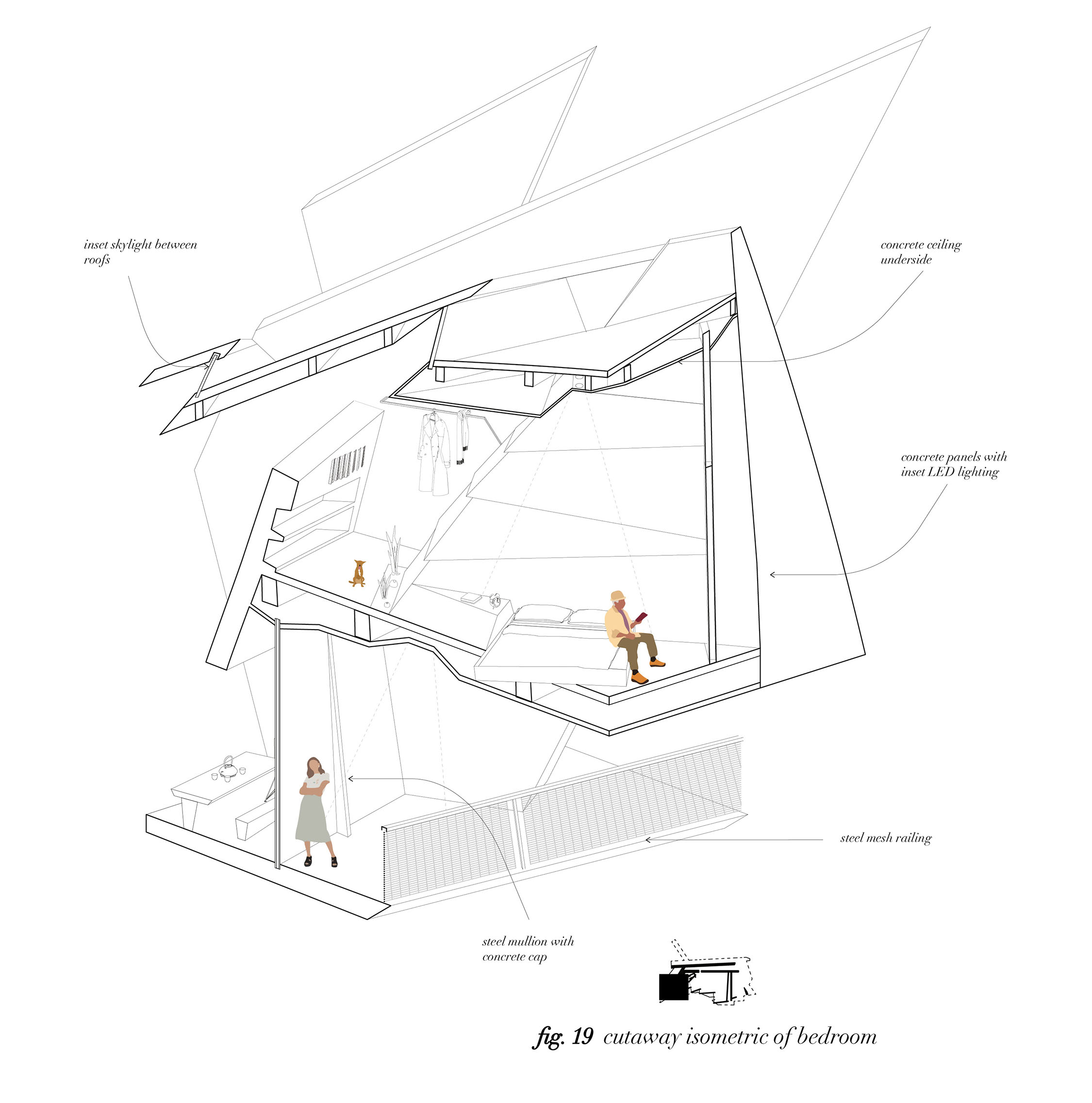

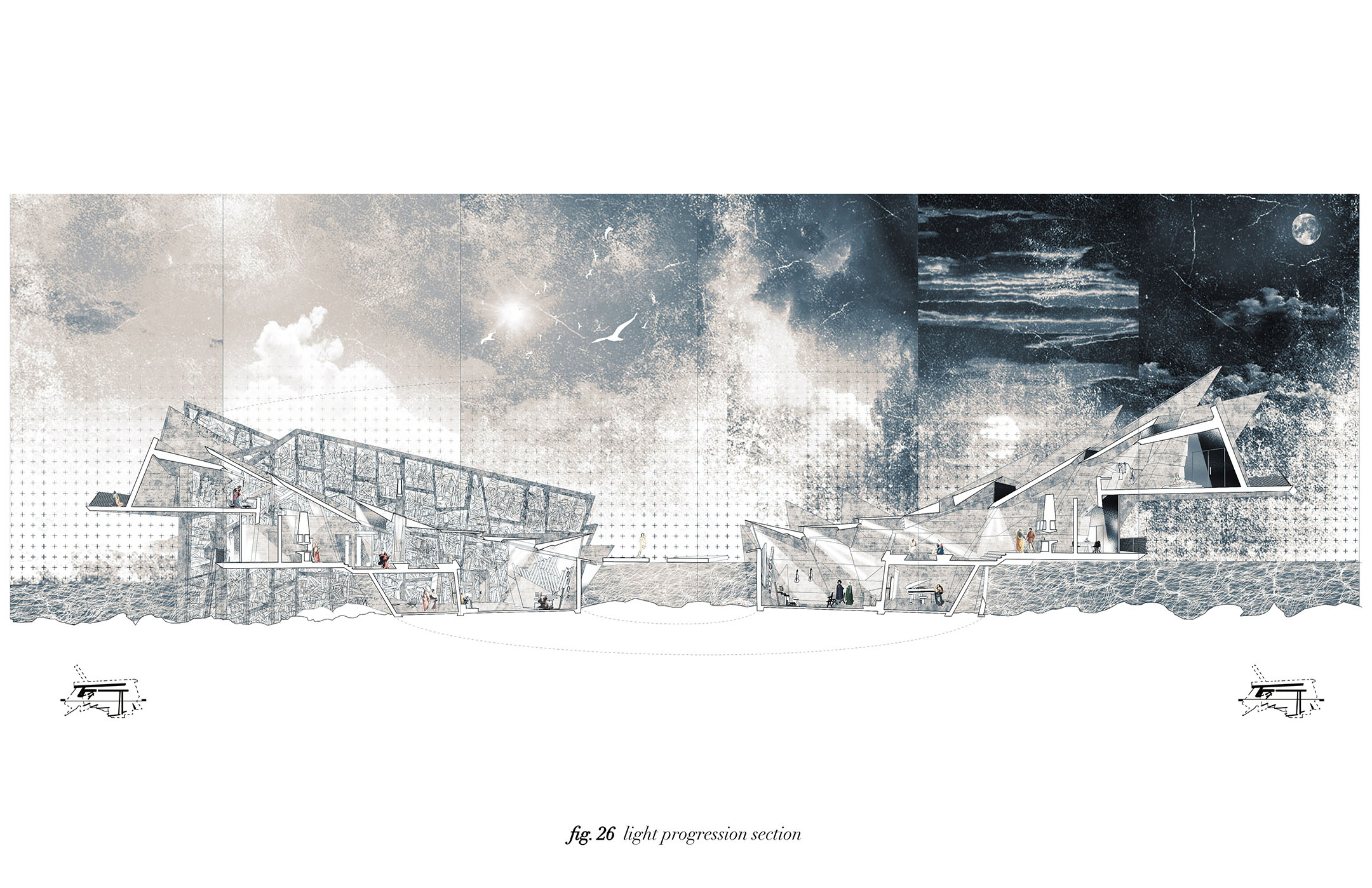

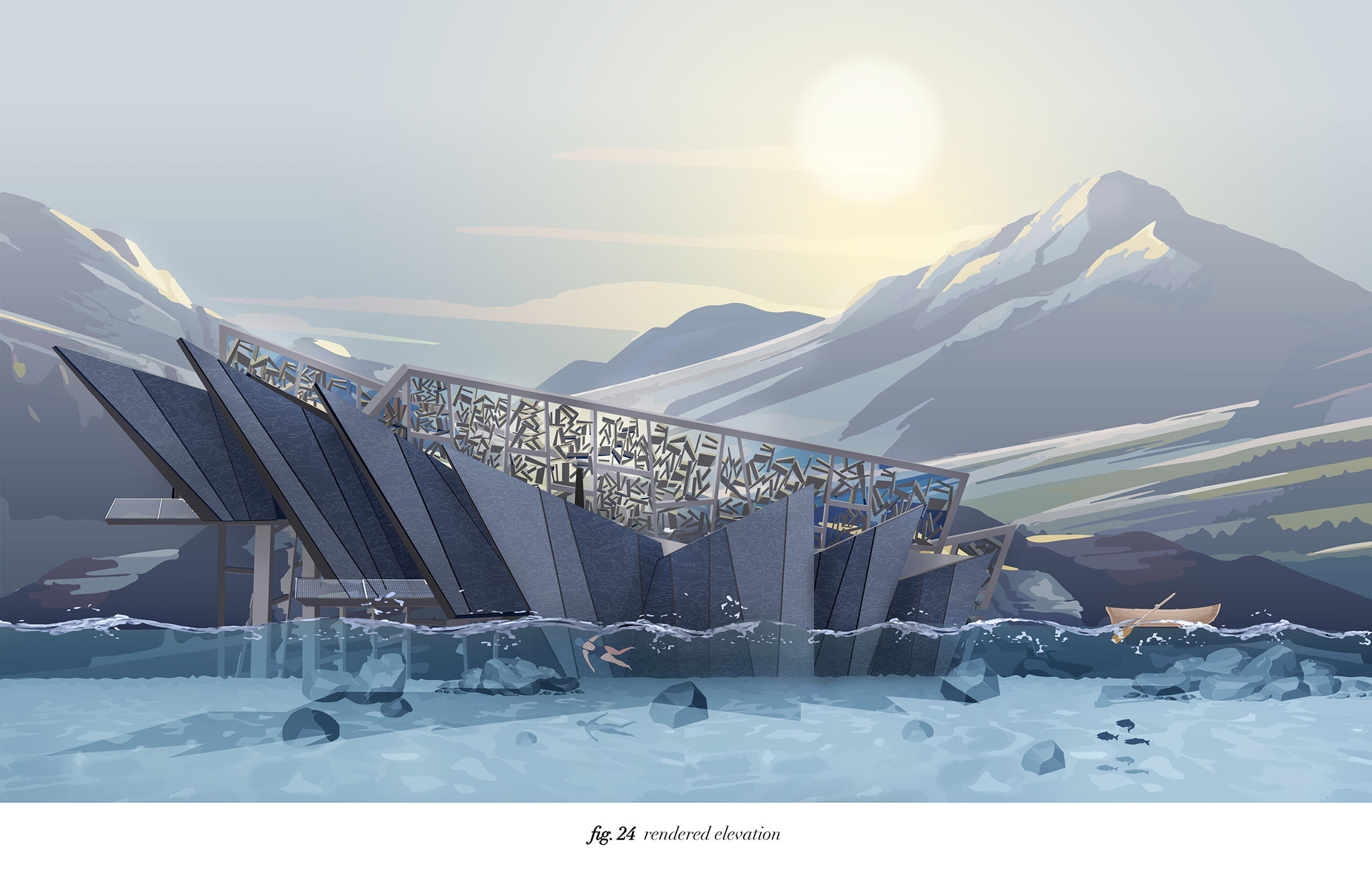

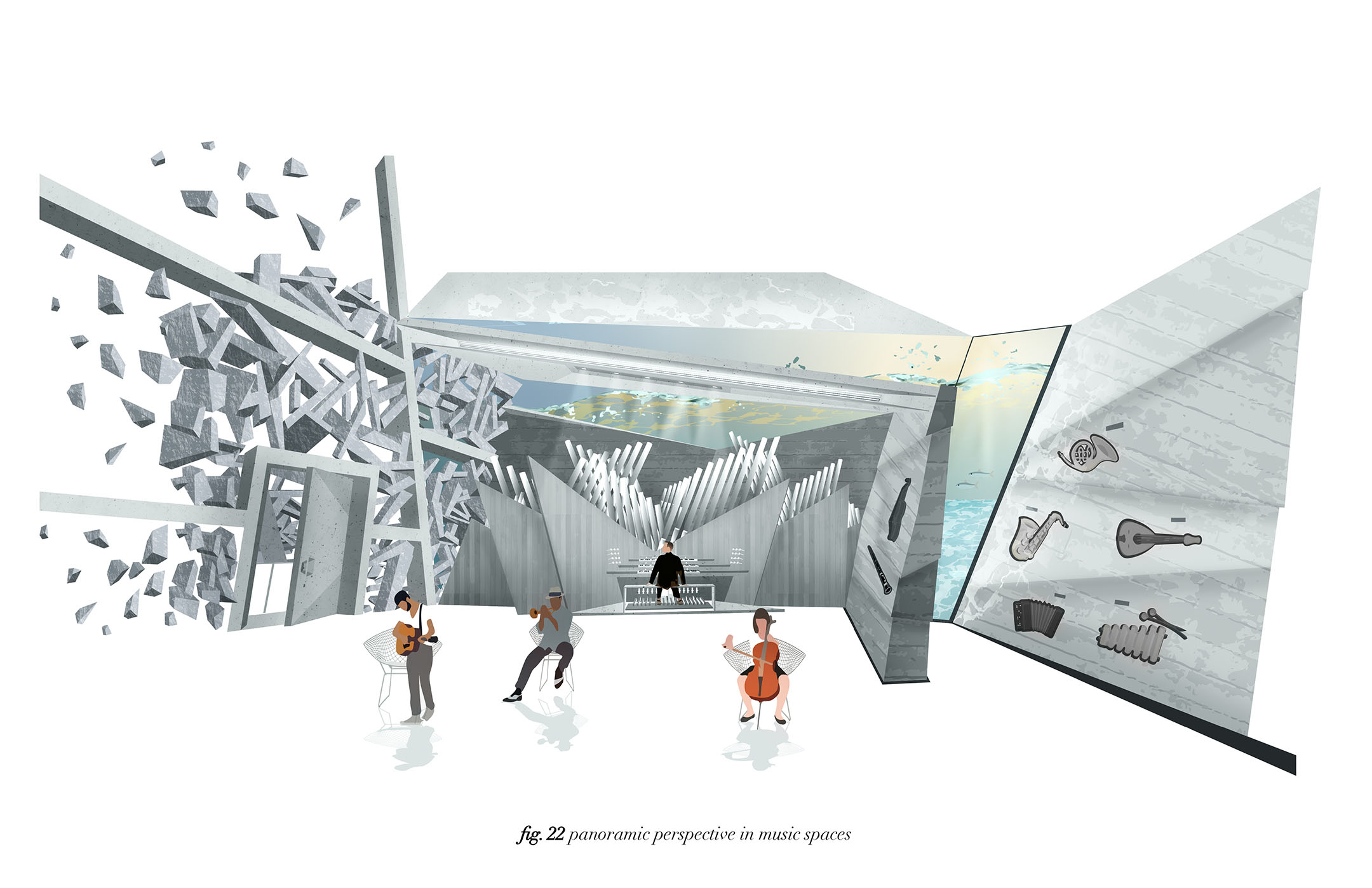

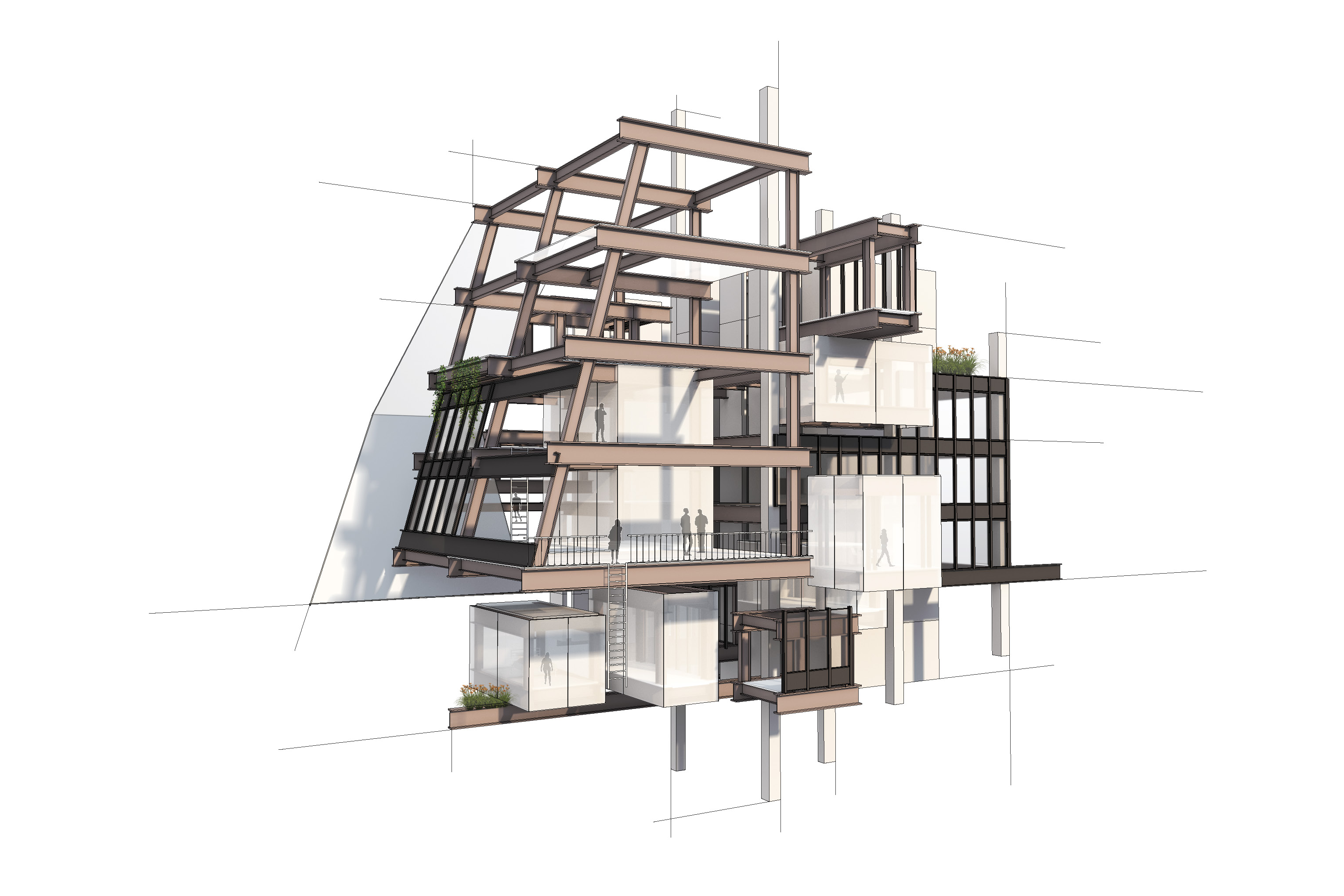

House for J.S. Bach

A residence for the famous composer and organist explores the fugal music structure through an architectural lens as an organizational approach to the architecture through play with fragmentation. Fragmentation of realities and cadences emerge from subdivision of spaces, fenestration, and light as well as from the segmentation of planes and materials.

Bach is well known for his Fugue compositions, musical pieces created using overlapping voices. As the organ instrument provides the organist with multiple manuals, the fugal structure capitalizes on this multiplicity by overlaying repeating melodies in different keys, thereby generating counterpoint. This music structure is explored as an organizational approach for the architecture through play with fragmentation.

Bach is well known for his Fugue compositions, musical pieces created using overlapping voices. As the organ instrument provides the organist with multiple manuals, the fugal structure capitalizes on this multiplicity by overlaying repeating melodies in different keys, thereby generating counterpoint. This music structure is explored as an organizational approach for the architecture through play with fragmentation.

A fragmented journey through the house, follows the experience of the client as they occupy the spaces. Entering from the dock, they enter the public living spaces. The central stairway serves to connect the various levels, with visitors able to ascend above to the bedrooms or descend below to the organ and composing rooms. Throughout the project, fugal musical structure is employed through fragmentation which is emphasized via the placement and form of architectural planes, but also by the light access and the placement of the artificial illumination.

Caitlin Chin

Project 2A - Individual Advanced Construction Tectonic and Material Study

Project 2A - Individual Advanced Construction Tectonic and Material Study

This assignment objective is to develop a deep understanding of the concept of Architecture as current and future artistic expression of tectonic materiality in an advanced constructed building, in a geographically relevant place. Students will look at the system of elements, techniques and technologies, current and as forecast and their affect on the practice of Architecture, the construction industry and sustainable futures. In addition, the project goal is to provide applied construction techniques and manufacturing in order to prepare the student for future professional engagement.

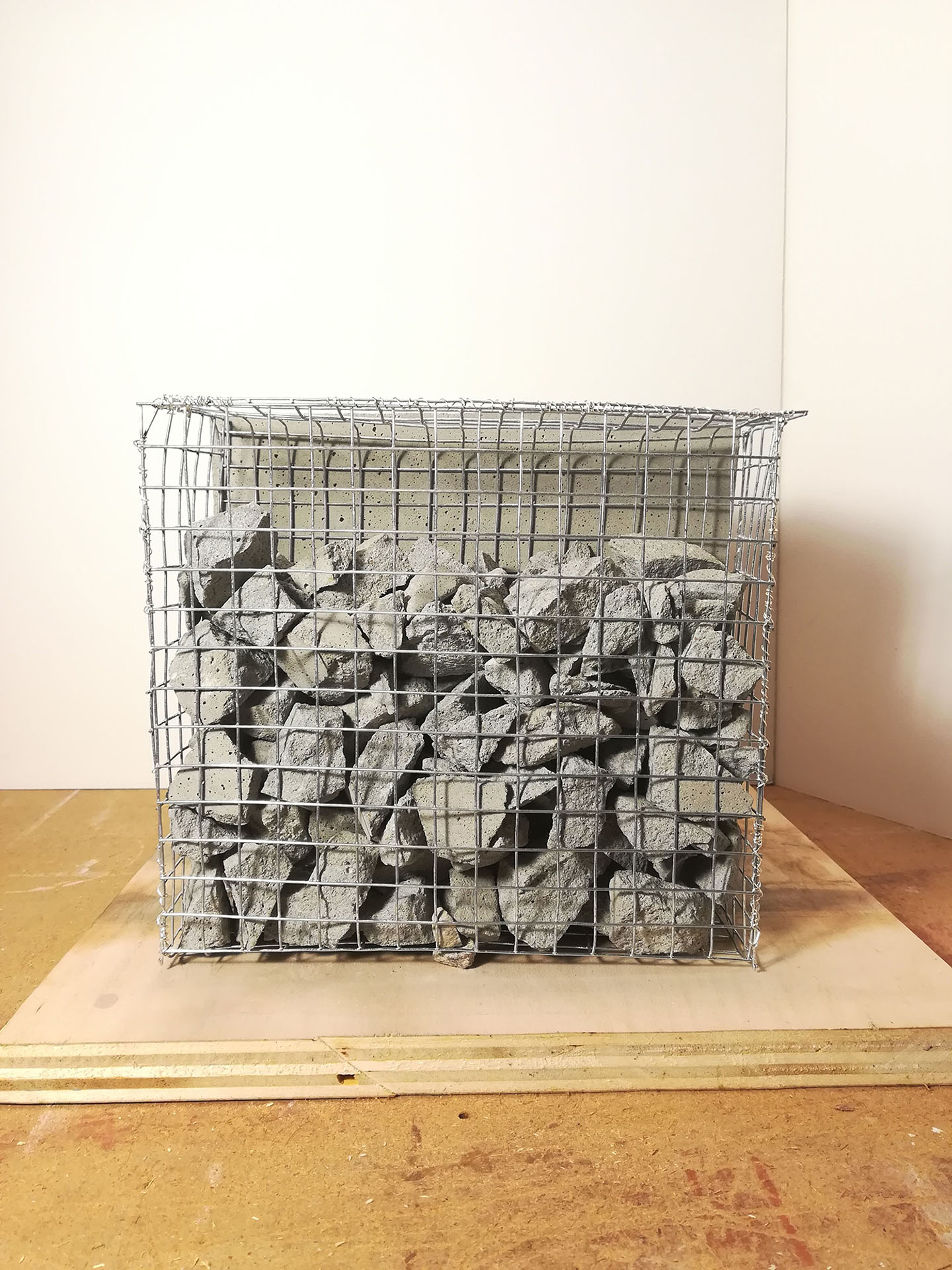

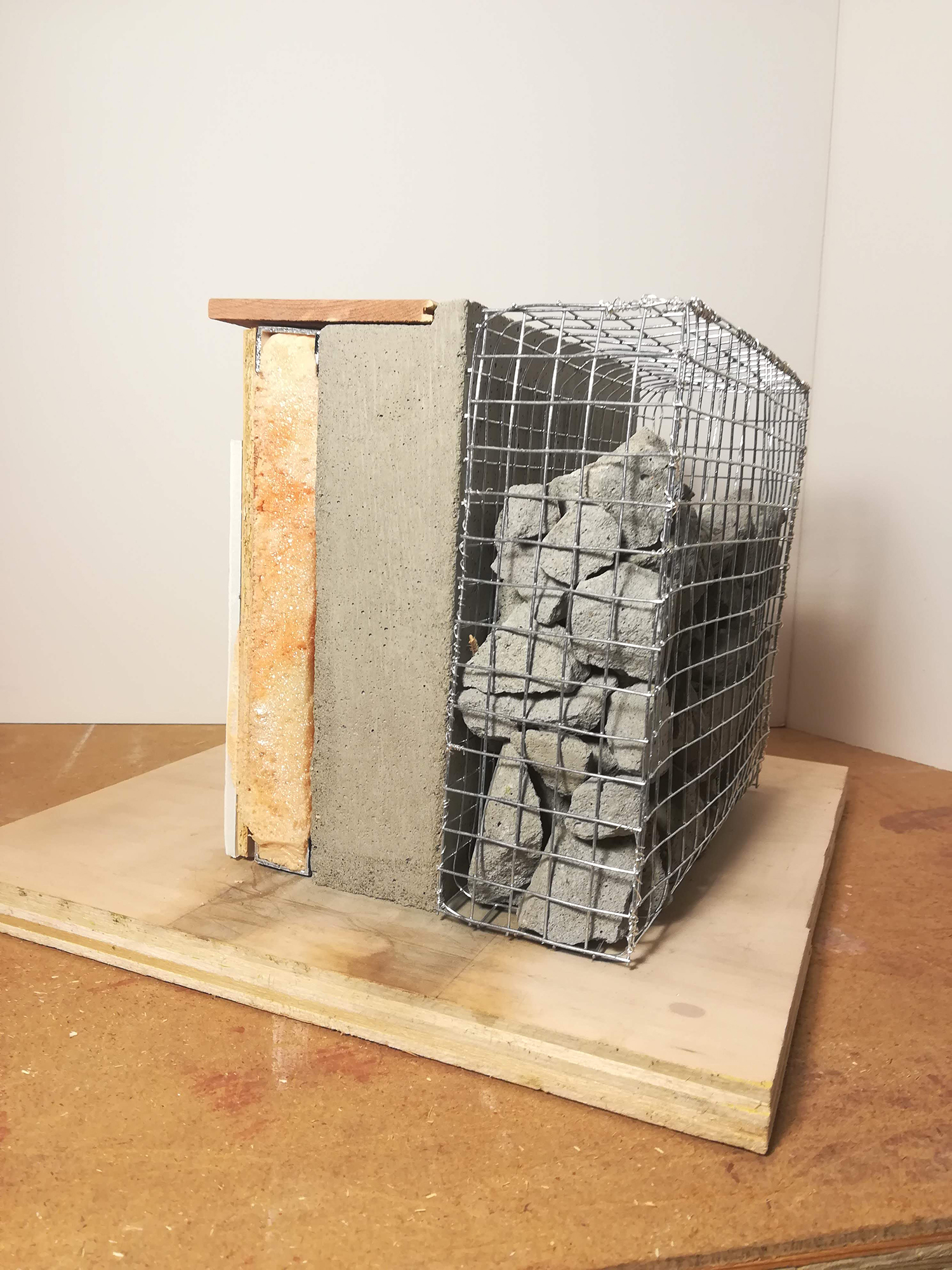

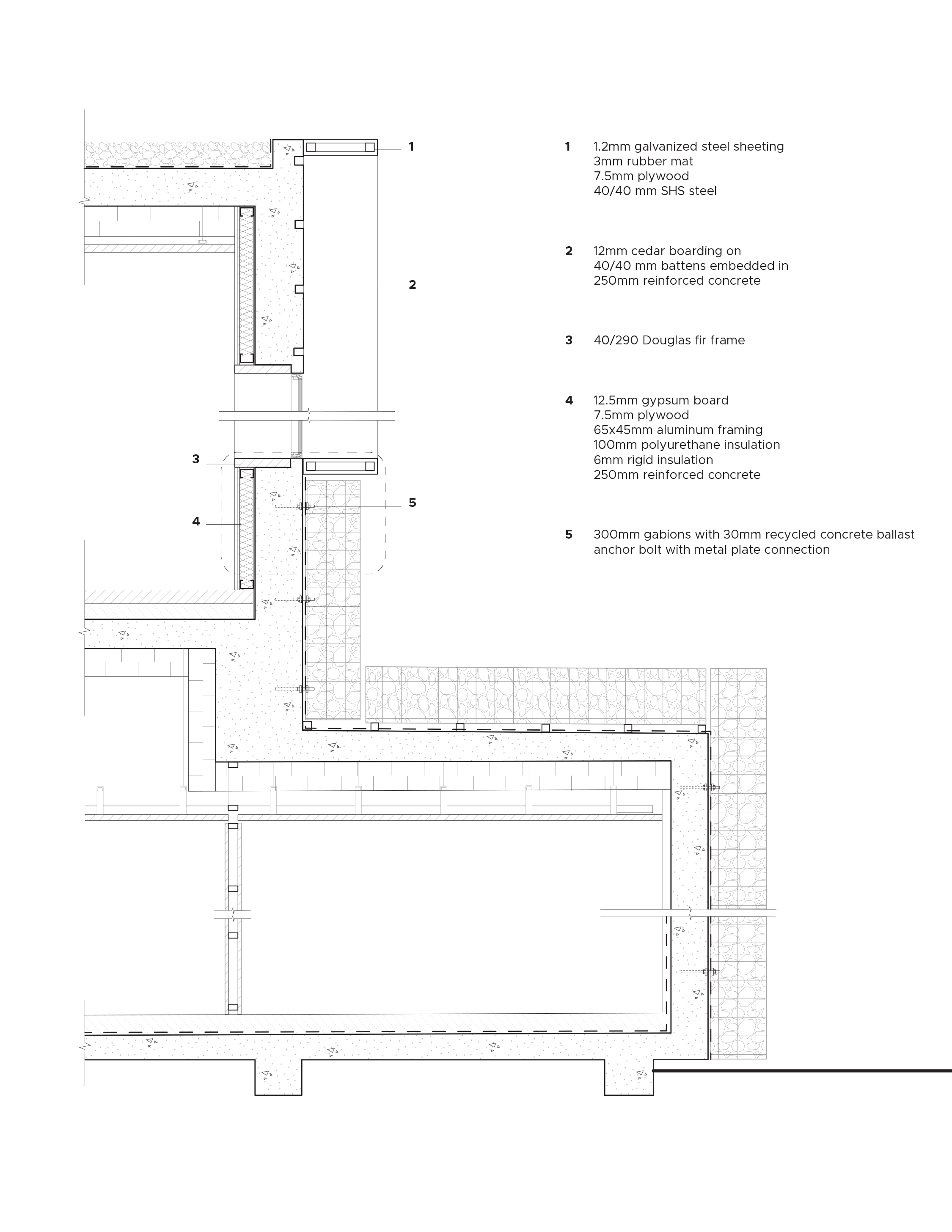

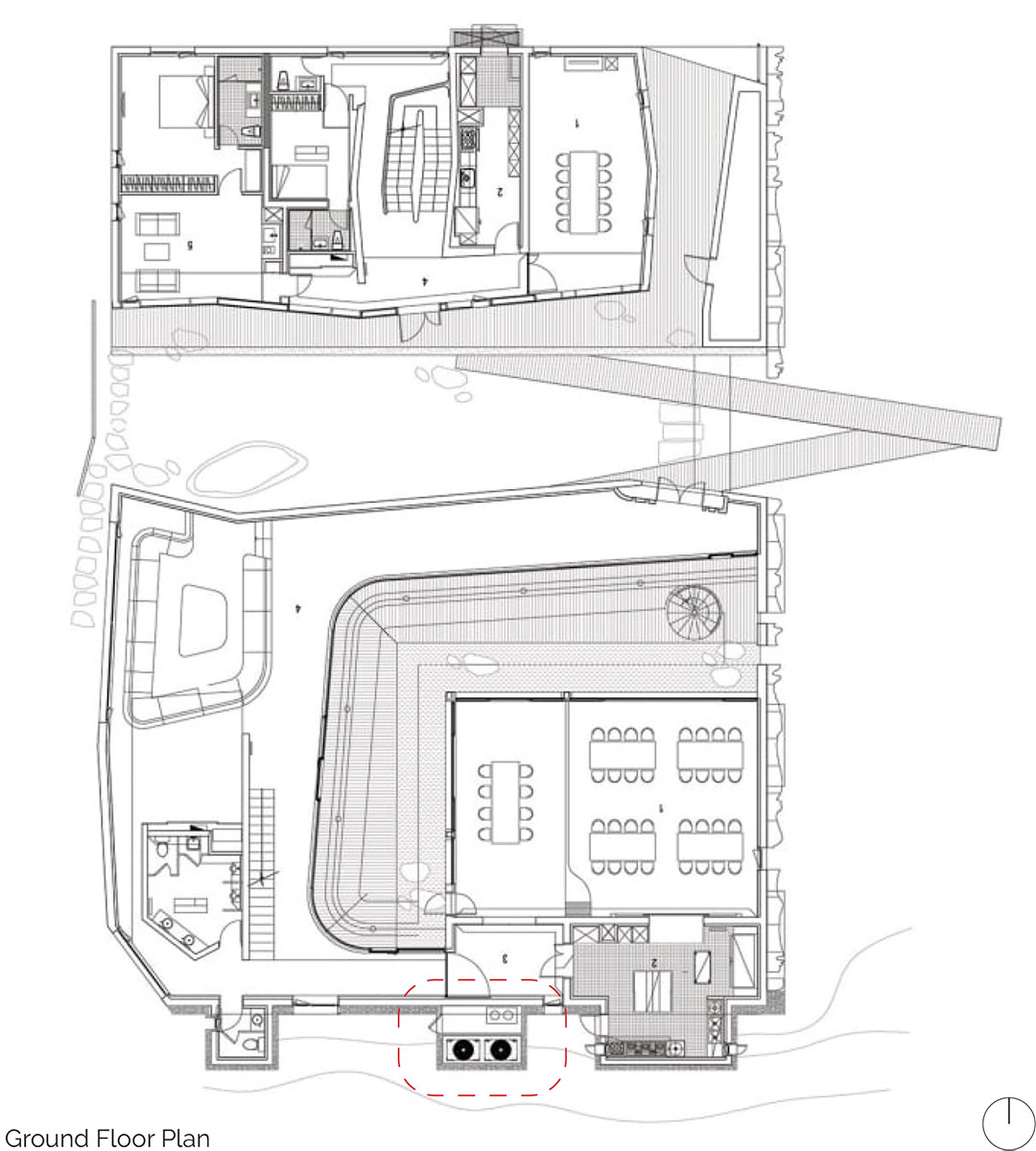

This building is a concrete building through and through. The main structure is made of reinforced concrete and the gabion cage is the exterior cladding. These gabion walls are filled with ballasts that is crushed concrete instead of stone which speaks their intention of recycling concrete. Because the gabion cage still allows rain and snow to interact directly with the structural wall, there is a sealant applied to the exterior side of the wall. Next will be the insulation, plywood and gypsum layers used for the interior finish of the wall. Douglas fir wood was also used as an accent material in this detail for the interior window frame. Their wood accents speak to their intention to reconnect with nature and their sustainable approach to concrete as the building is right beside Mt. Sobaek National Park.

How it relates to the Overall Conception:

The Hanil cement plant, the client of the Hanil Visitor Centre & Guest House, acknowledges the environmental impact of concrete as a problem. The intention of the visitor centre and guest house is to educate visitors about recycled concrete. The building itself showcases the potential of recycled concrete through different types of formwork and casting techniques in its own construction. As mentioned before the ballasts used for the gabion wall was crushed, leftover concrete of the east wall which supports their goal into looking at new ways of recycling concrete. This introduces the concept of a closed loop construction process between the waste of the east wall to be reused in the south wall. The crushed concrete was also used for the roof, interior railings in gabion cages and larger ballasts were integrated into the landscape design. The future for this interpretation of the gabion wall provides opportunity of using recycled concrete ballasts without worrying about the structural integrity of the concrete.

Why the Detail was Chosen:

The chosen detail is the south gabion wall of the Hanil Visitor Centre & Guest House in Korea. This wall acts as one of the main facades of the building along with the east fabric formed wall. The construction of the wall is significant because it reinterprets the typical use of a gabion wall. Traditionally, gabion walls are filled with stone and used as a retaining wall, but in this project the leftover concrete from the east wall was crushed to take the place of the stone. Therefore, the gabion wall acts more as a cladding element that is attached to the reinforced concrete wall behind it.

Caitlin Chin

Project 2B - Tectonic and Material Design, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship

Project 2B - Tectonic and Material Design, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship

The assignment objective is to develop in the students the primary ingredients of design, innovation and entrepreneurship required for the architectural and construction industries. The professional scope of the Architect is changing dramatically in the 21st century. In the future, Architect’s ideas will permeate the fabrication process in its entirety. A new relationship is being established between the Architect’s traditional responses towards advanced construction in terms of tectonics and materiality.

The Hanil Visitor Centre and Guest House

Location: 77, Pyeong-ri, Maepo-eup, Danyang-gun, Chungbuk, Korea

Architect: Byoung-soo Cho (BCHO Architects)

Client: Hanil Cement Plant

![]()

Refabrication: New Material Concept

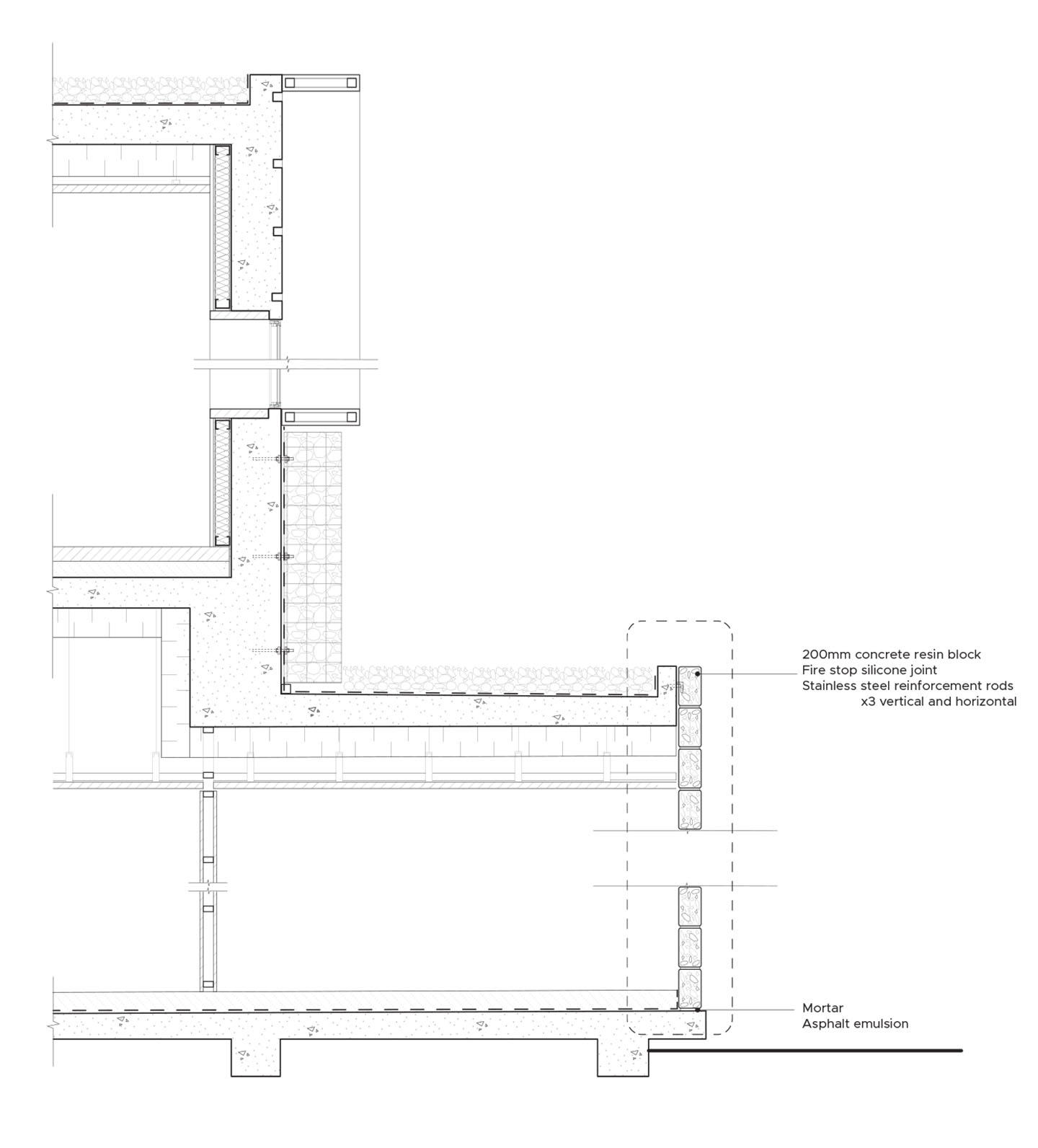

The Hanil cement plant, the client of the Hanil Visitor Centre & Guest House, acknowledges the environmental impact of concrete as a problem. Within the visitor and guest house contains samples of different ways the Hanil Cement Plant has been experimenting with various methods of using concrete. They have the intention of coming up with new ways to use concrete in non-typical ways and combining it with other materials and methods. The south wall currently has the exterior cladding as a gabion cage wall that uses recycled concrete as ballasts. However, the construction currently in place has the cage connected flat against the solid surface of the structural reinforced concrete wall. The program of the ground floor can benefit from natural daylight. The specific detail is of the electrical room that is indicated on the plan. So instead of the gabion cage, the translucent tile that the center has been experimenting with can be an alternate cladding material to allow light to enter the interior space and to display another method of recycling concrete on the building. Also in the current detail there is no interior or exterior insulation for this space, which allows for some material experimentation.

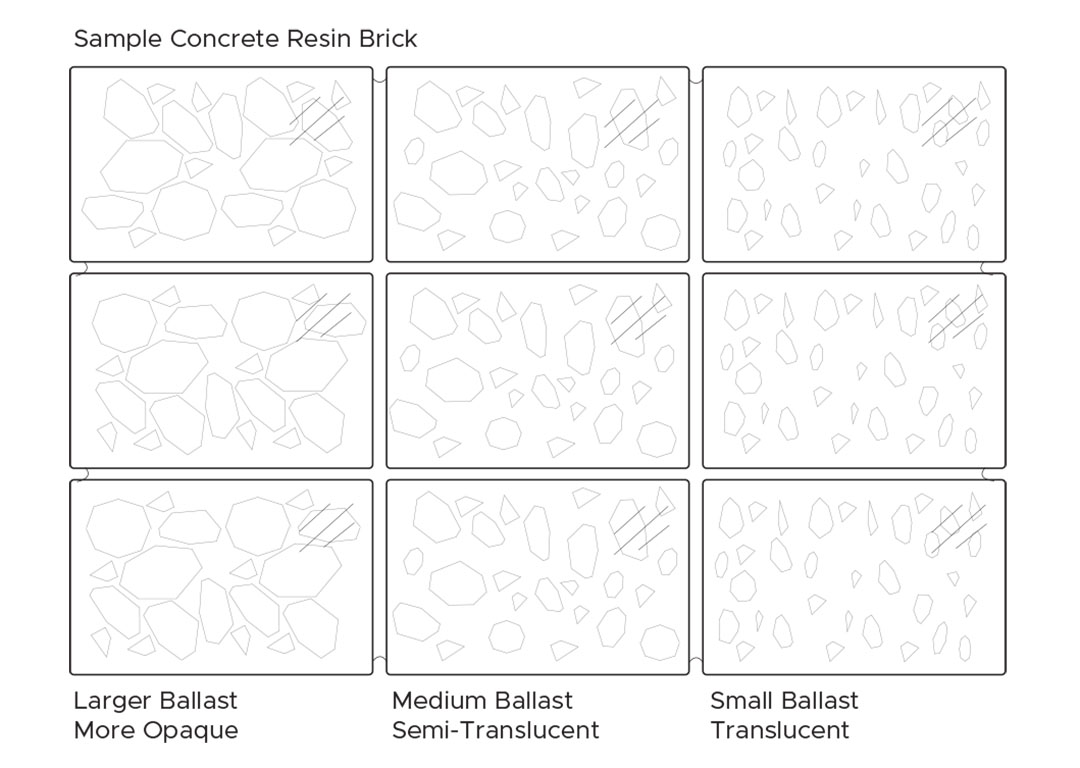

The material alternative is an option seen on the right. The tile has the crushed concrete and then resin is poured over the ballasts. The amount of concrete within the tile and the pattern that the concrete pieces can make is all customizable. As seen on the examples on display, some tiles have the concrete emerging from the resin while in others the concrete is fully submerged. It can also have different finish qualities to the surface. It can be glossy or matte.

Location: 77, Pyeong-ri, Maepo-eup, Danyang-gun, Chungbuk, Korea

Architect: Byoung-soo Cho (BCHO Architects)

Client: Hanil Cement Plant

Refabrication: New Material Concept

The Hanil cement plant, the client of the Hanil Visitor Centre & Guest House, acknowledges the environmental impact of concrete as a problem. Within the visitor and guest house contains samples of different ways the Hanil Cement Plant has been experimenting with various methods of using concrete. They have the intention of coming up with new ways to use concrete in non-typical ways and combining it with other materials and methods. The south wall currently has the exterior cladding as a gabion cage wall that uses recycled concrete as ballasts. However, the construction currently in place has the cage connected flat against the solid surface of the structural reinforced concrete wall. The program of the ground floor can benefit from natural daylight. The specific detail is of the electrical room that is indicated on the plan. So instead of the gabion cage, the translucent tile that the center has been experimenting with can be an alternate cladding material to allow light to enter the interior space and to display another method of recycling concrete on the building. Also in the current detail there is no interior or exterior insulation for this space, which allows for some material experimentation.

The material alternative is an option seen on the right. The tile has the crushed concrete and then resin is poured over the ballasts. The amount of concrete within the tile and the pattern that the concrete pieces can make is all customizable. As seen on the examples on display, some tiles have the concrete emerging from the resin while in others the concrete is fully submerged. It can also have different finish qualities to the surface. It can be glossy or matte.

Resin Material Properties:

Casting resin is specifically designed to be casted into molds, forms, and figures. The two components of casting resin that makes it an interesting material is the low-viscosity and the ability to harden over time. Because of these properties casting resin can be used for projects that require a thicker application/ depth. Casting resin differs from epoxy resin. Epoxy resin is more viscous, has a faster curing time but can only be applied to projects with a maximum depth of 2cm (Resin Expert, 2020).

Looking into specific products for casting resin is a thermosetting resin, specifically made from polyethylene terephthalate. It is highly transparent and stiff, and it has excellent gas barrier properties. Some example of products that are made from this material is insulation, and high-performance optical films (Daido Chemical Corporation).

When in the process of casting, formwork needs to be considered. It is recommended to use silicone molds to allow for a smooth finish but also allows for easy removal of the mold. The first step would be to have a thin layer of resin in the mold to begin with and then to add the desired amount and pattern of the recycled concrete pieces. Next, additional casting resin will be poured over concrete pieces and to reach the desired thickness. It is recommended to dry for 24 hours but it also varies based on the thickness of the piece casted.

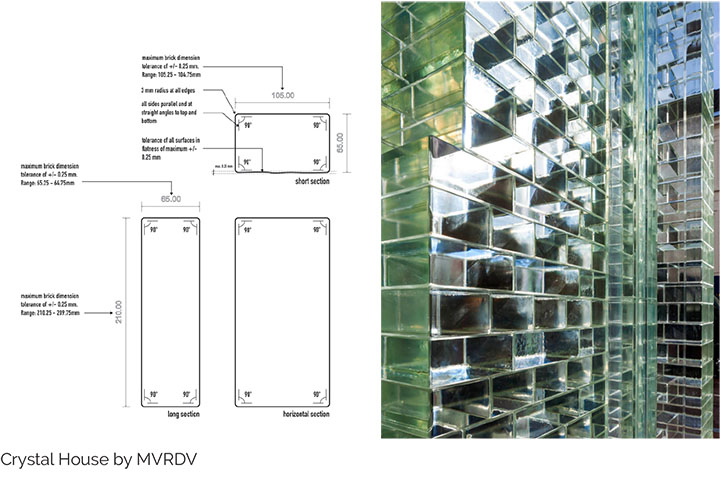

I am looking at the thin resin tiles that the Hanil Cement Plant has experimented with and making it into something that is thicker, and block like. I will be looking at glass blocks and their construction methods of wall construction for the proposed resin blocks.

Glass Block History:

The invention of glass has made a huge impact on the building industry as it allows natural daylight and views to be accessible from the interior of the building. The use of glass blocks has been reinvented over the years as it has varied in use as an interior or exterior element in the form of walls, ceilings, and floors. Glass blocks have been important in the interior architectural design to illuminate adjacent rooms and hallways mainly. The glass can be manufactured to provide the desired degree of visibility to allow for privacy and light permeability. In the exterior context, glass blocks maximize natural light to reduce energy required for artificial lighting (Architectural Products and Services, 2018).

In 1907, Deutsche Luxfer-Prismen-Gesellschaft patented the glass block strengthening process where the two pieces of glass are joined but the centre is hollow. The “air gap” within enhances the insulating qualities that glass blocks and helps with sound deadening, and fireproofing. In present day context, the pattern, texture degree of transparency and size can all be customized for any project. Additionally, over the years different mortars and silicones have been improving to join the glass blocks together (Architectural Products and Services, 2018).

I am hoping to explore and treat the resin concrete blocks similarly to the glass block construction. I will be referring to different modern examples that used glass blocks in an innovative way and looking at different details that I can learn from for the resin concrete blocks.

![]()

The invention of glass has made a huge impact on the building industry as it allows natural daylight and views to be accessible from the interior of the building. The use of glass blocks has been reinvented over the years as it has varied in use as an interior or exterior element in the form of walls, ceilings, and floors. Glass blocks have been important in the interior architectural design to illuminate adjacent rooms and hallways mainly. The glass can be manufactured to provide the desired degree of visibility to allow for privacy and light permeability. In the exterior context, glass blocks maximize natural light to reduce energy required for artificial lighting (Architectural Products and Services, 2018).

In 1907, Deutsche Luxfer-Prismen-Gesellschaft patented the glass block strengthening process where the two pieces of glass are joined but the centre is hollow. The “air gap” within enhances the insulating qualities that glass blocks and helps with sound deadening, and fireproofing. In present day context, the pattern, texture degree of transparency and size can all be customized for any project. Additionally, over the years different mortars and silicones have been improving to join the glass blocks together (Architectural Products and Services, 2018).

I am hoping to explore and treat the resin concrete blocks similarly to the glass block construction. I will be referring to different modern examples that used glass blocks in an innovative way and looking at different details that I can learn from for the resin concrete blocks.

Chanel Wase

Project 2A - Individual Advanced Construction Tectonic and Material Study

Project 2A - Individual Advanced Construction Tectonic and Material Study

SANAA New Contemporary Art Museum

This assignment objective is to develop a deep understanding of the concept of Architecture as current and future artistic expression of tectonic materiality in an advanced constructed building, in a geographically relevant place. Students will look at the system of elements, techniques and technologies, current and as forecast and their affect on the practice of Architecture, the construction industry and sustainable futures. In addition, the project goal is to provide applied construction techniques and manufacturing in order to prepare the student for future professional engagement.

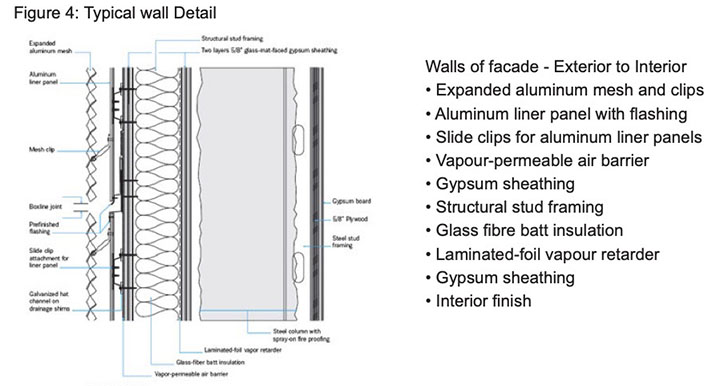

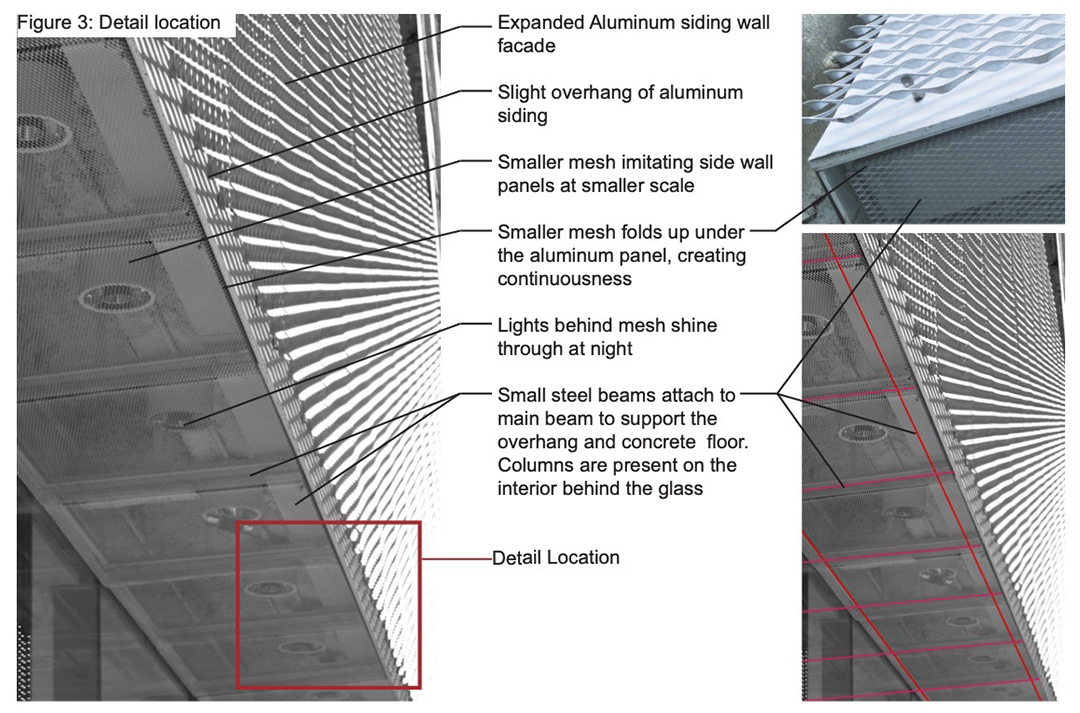

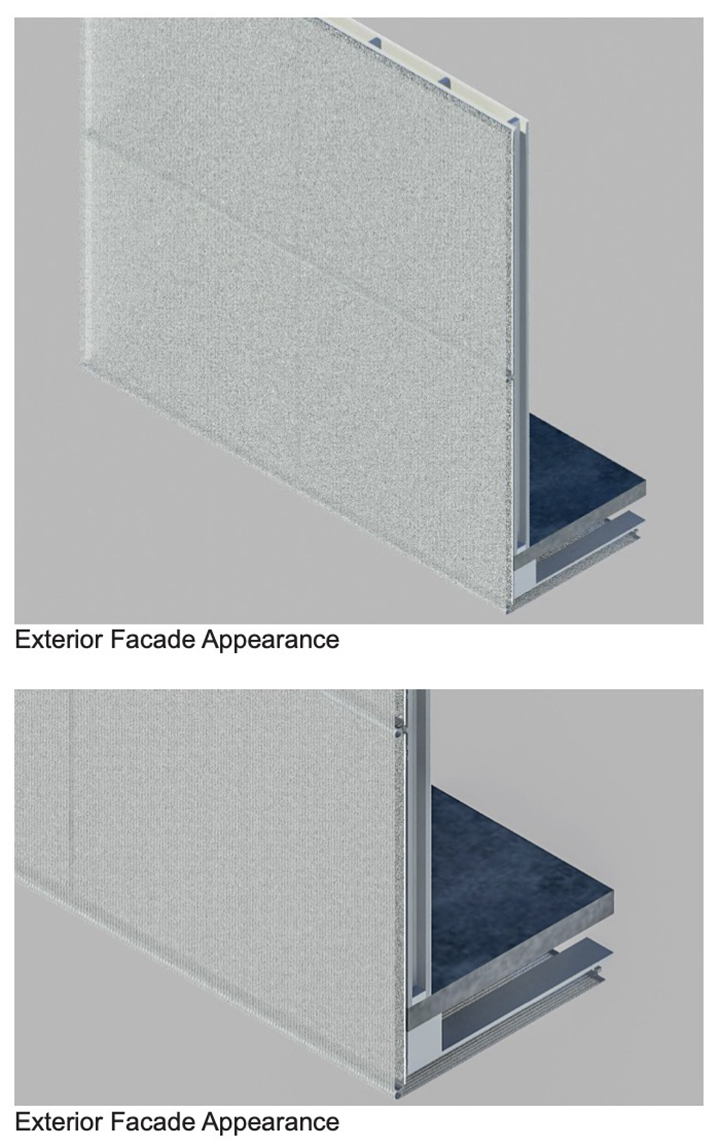

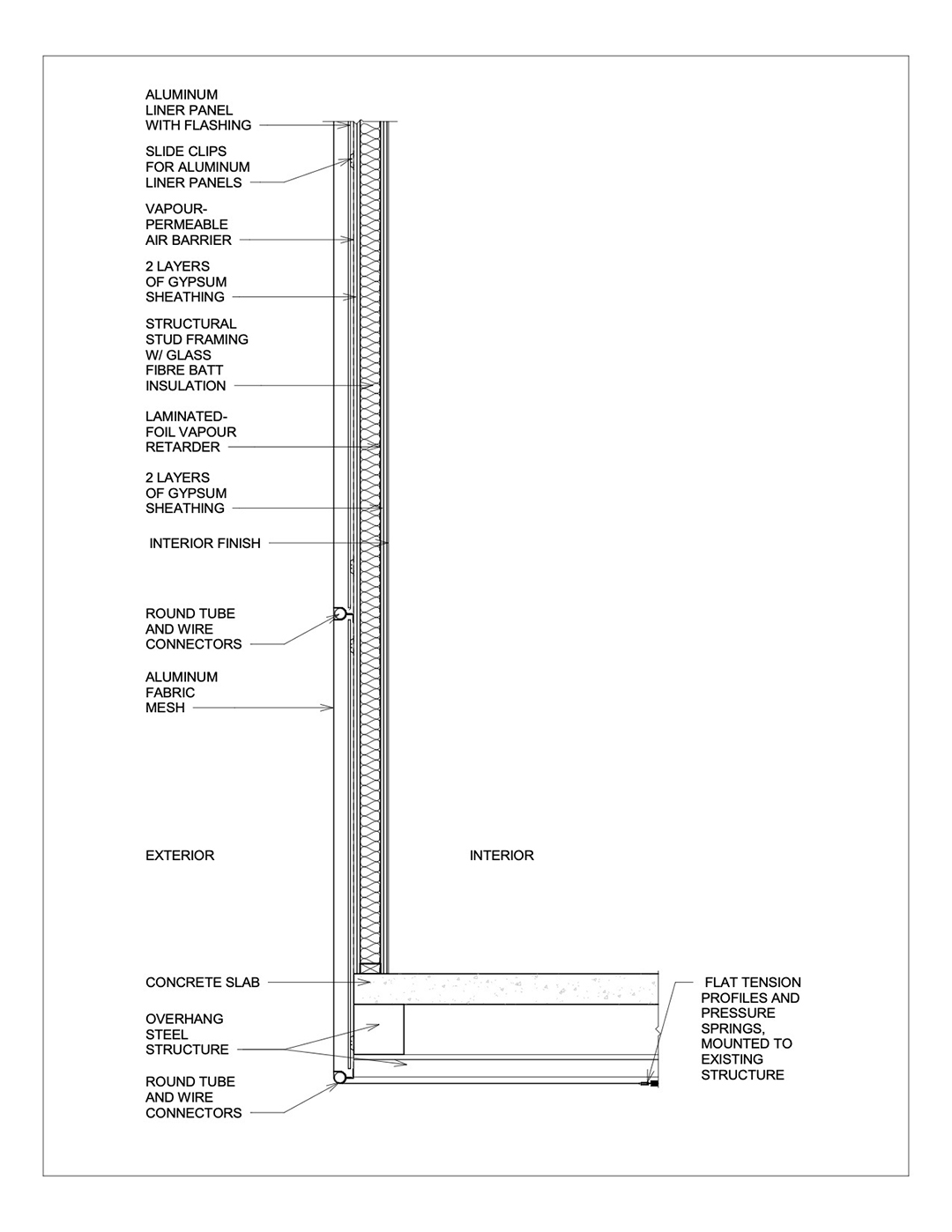

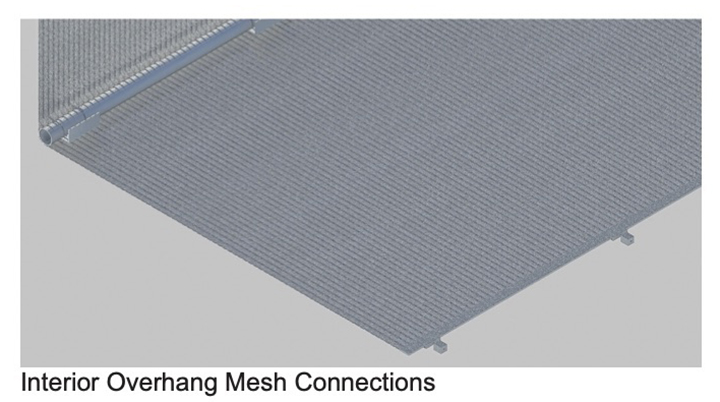

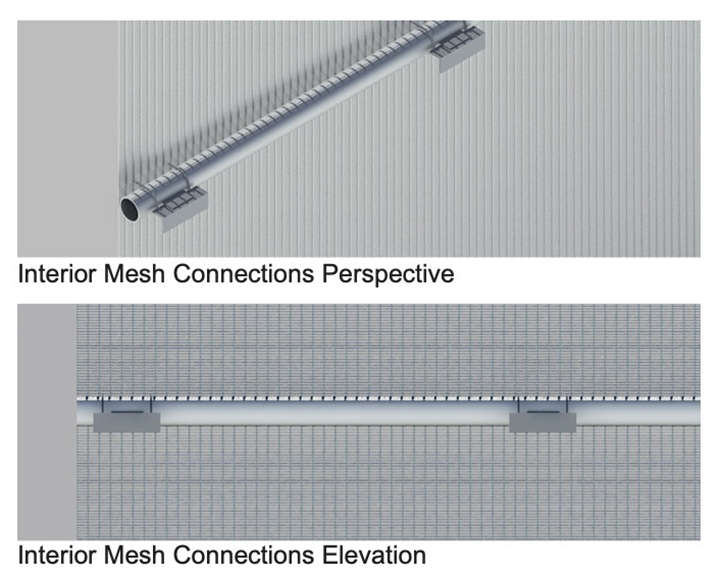

The detail being studied is taken from the overhang at the entrance of The New Art Museum by SANAA architects (Figure 1). The concept behind the building was to create shifting boxes which fit in and reflect the New York cityscape where it is located. From a distance, the building is seen to be clean and monochrome, and fits in well with the cityscape, but upon closer inspection, it is made up of a more industrial continuous mesh facade. This can be seen as a metaphor for the New York cityscape in general.

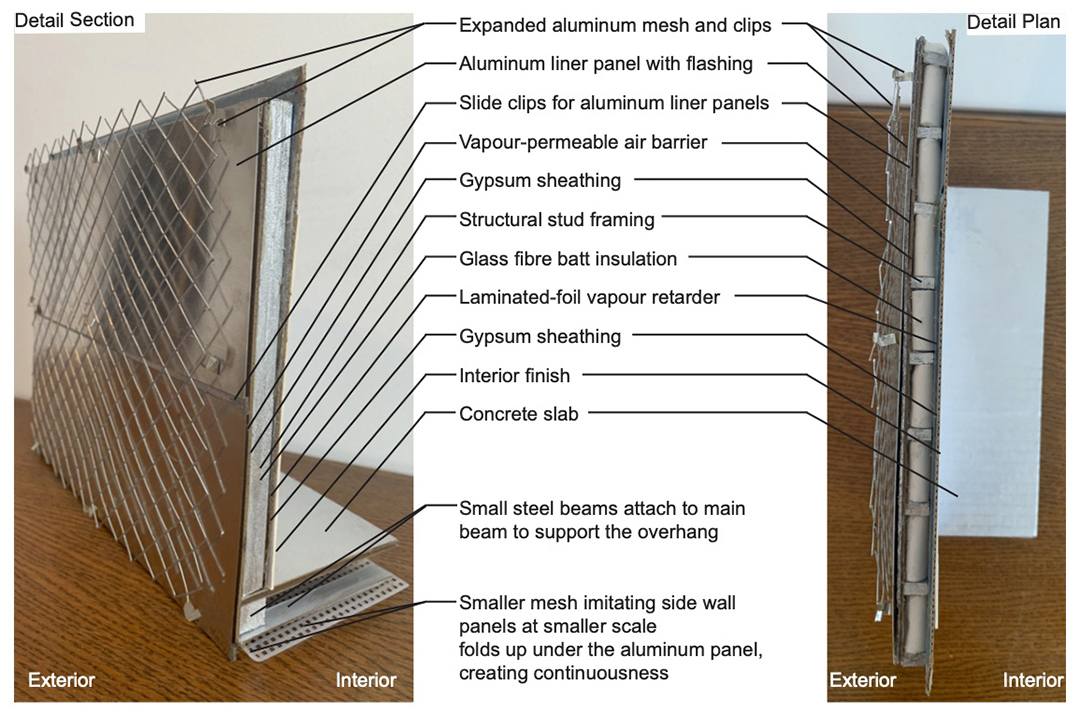

The building’s facade is made up of an anodized expanded aluminium mesh bolted directly to aluminum panelled walls (Figure 4). Aluminum was chosen due to its light weight and cost efficiency. This aluminum mesh skin wraps the entire building, softening its edges and hiding the windows throughout the day. This was meant to allow the building to melt into its surroundings and increase its sense of transparency and lightness. The mesh panels themselves are made to a standard size to reduce costs, each 4’ long with 6 diamond shapes of width. The separate panels are overlapped at the centre of the diamond shape to hide the joints and allow for the appearance of a continuous wall. The clips which attach the aluminum mesh to the interior aluminum panels are steel, which may cause problems in the future due to being a different metal. However, they are strong supports, and are made at an angle in relation to the angled diamond shapes of the mesh panels, which allows them to remain hidden out of view, also contributing to the continuous look of the facade.

The expanded aluminium mesh on the facade is a material usually used for fencing, but SANAA was able to demonstrate a new way to use this material as a continuous skin for a building. Their research into this detail is not yet perfect, as the joints at the corner of the building are not continuous, and they are criticized for the interior look of the mesh through the windows. However, this use of aluminum mesh may be, and has been, re-fabricated and customized into other similar building facades. It is a good precedent to see how a non-traditional material can be used for aesthetic and building purposes as a skin on a facade.

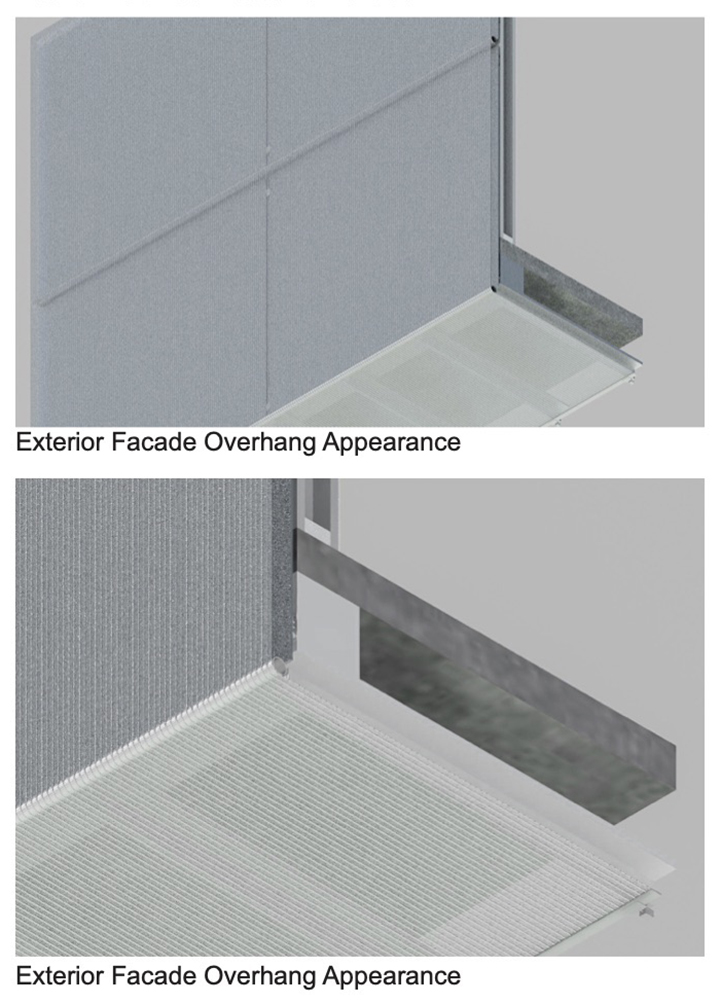

In order to demonstrate transparency to the outside world, the main entrance of the New Art Museum has a large glass wall, and continues the exterior concrete sidewalk into the interior (Figure 1). This entrance includes a small overhang of the building above. Unlike other overhangs present in the building, which simply use white panels to close off the overhang’s bottom, this one is more visible to passerby, and is more detailed to accommodate this. The bottom of the overhang is covered by a small metal mesh which turns up to seamlessly hide behind where the aluminum mesh panels of the wall’s facade hang down (Figure 3). The use of a mesh below the overhang allows for the continuous feeling of the building’s facade to remain unbroken to people walking under.

This overhang mesh detail also imitates the building’s interior skylights, which are one of the main natural light sources inside of the building, created in the spaces between the shifting box shapes. By putting lights behind the overhang’s mesh where the structure is, the overhang shines down light at night, just like the actual skylights which shine in the interior (Figure 2). This also enforces the concept of transparency and connection between interior and exterior.

Chanel Wase

Project 2B - Tectonic and Material Design, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship

Project 2B - Tectonic and Material Design, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship

Metal Mesh Facade

The assignment objective is to develop in the students the primary ingredients of design, innovation and entrepreneurship required for the architectural and construction industries. The professional scope of the Architect is changing dramatically in the 21st century. In the future, Architect’s ideas will permeate the fabrication process in its entirety. A new relationship is being established between the Architect’s traditional responses towards advanced construction in terms of tectonics and materiality.

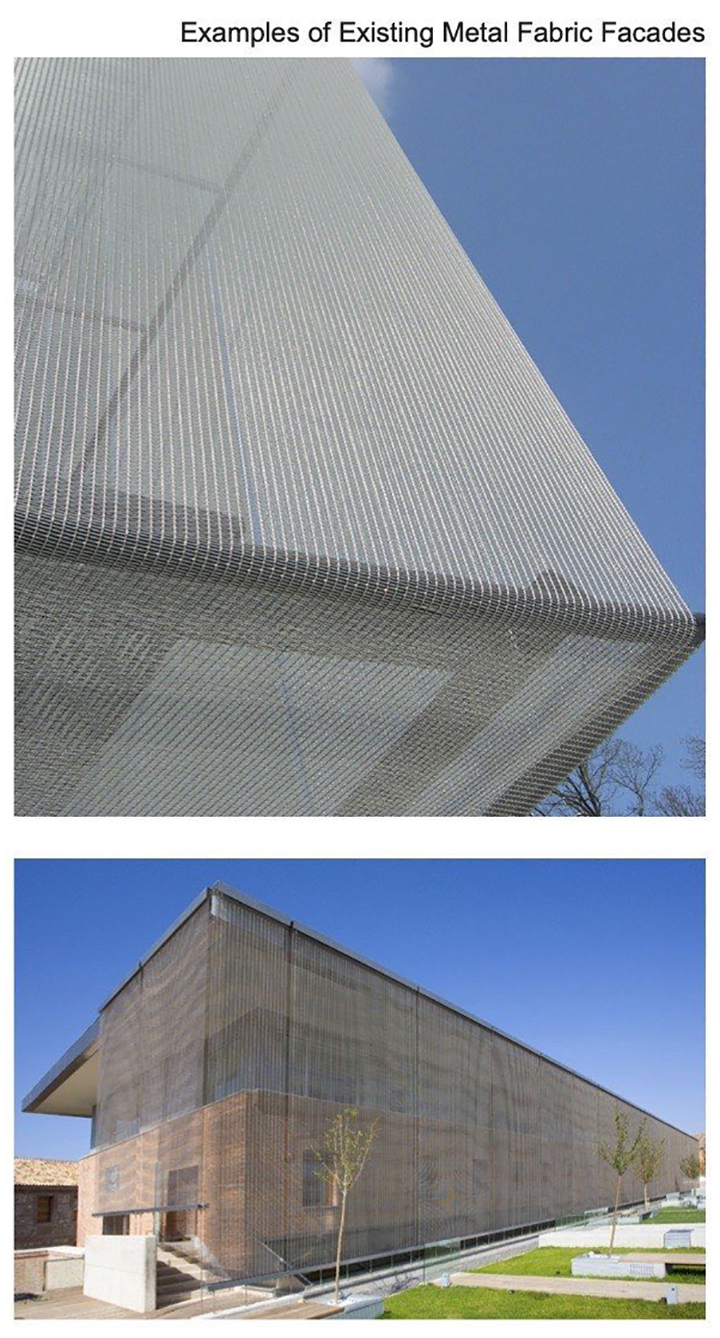

The facade detail of the New Art Museum by SANAA architects has been greatly studied for the completion of this assignment. The concept behind the building was to create shifting boxes which fit in and reflect the New York cityscape where it is located. From a distance, the building is seen to be clean and monochrome, and fits in well with the cityscape, but upon closer inspection, it is made up of a more industrial continuous mesh facade. This can be seen as a metaphor of the New York cityscape in general.

The expanded aluminium mesh on the facade skin wraps the entire building, softening its edges and hiding the windows throughout the day. This was meant to allow the building to melt into its surroundings and increase its sense of transparency and lightness, as well as give it a sense of blurred lines and edges. The use of aluminum panels behind the mesh also give a shallow depth and clean look to the facade.

Upon studying this detail, one of the main critiques which can be found is the fact that the facade is not actually as continuous as it is meant to appear. For example, at the corners of the building, the mesh skin does not join together, and at the bottom of the overhangs, a completely different mesh is used. Perhaps due to the budget, or because “the quality of craftsmanship in New York is known to be substandard” the building is not as detailed as it could have been in some specific areas (Ouroussoff 2007). The interior look of the mesh through the windows is also criticized, as it does not act as a true shading device, and has a very cold look to it. “Seen from outside, the strip windows there emit a blurred glow through the mesh. But from within, the metal creates a dispiritingly correctional effect: inmates look through the grate at a skyline partitioned into little diamonds” (Davidson 2001).

The most critical detail of this building is, of course, the mesh skin. However, it can also be considered as one of the main issues with the facade of the building. When looking into this detail, it can be considered that perhaps a certain change in materiality and nature may fix many of the issues noted above, while still remaining true to the nature of the building and its design concept.

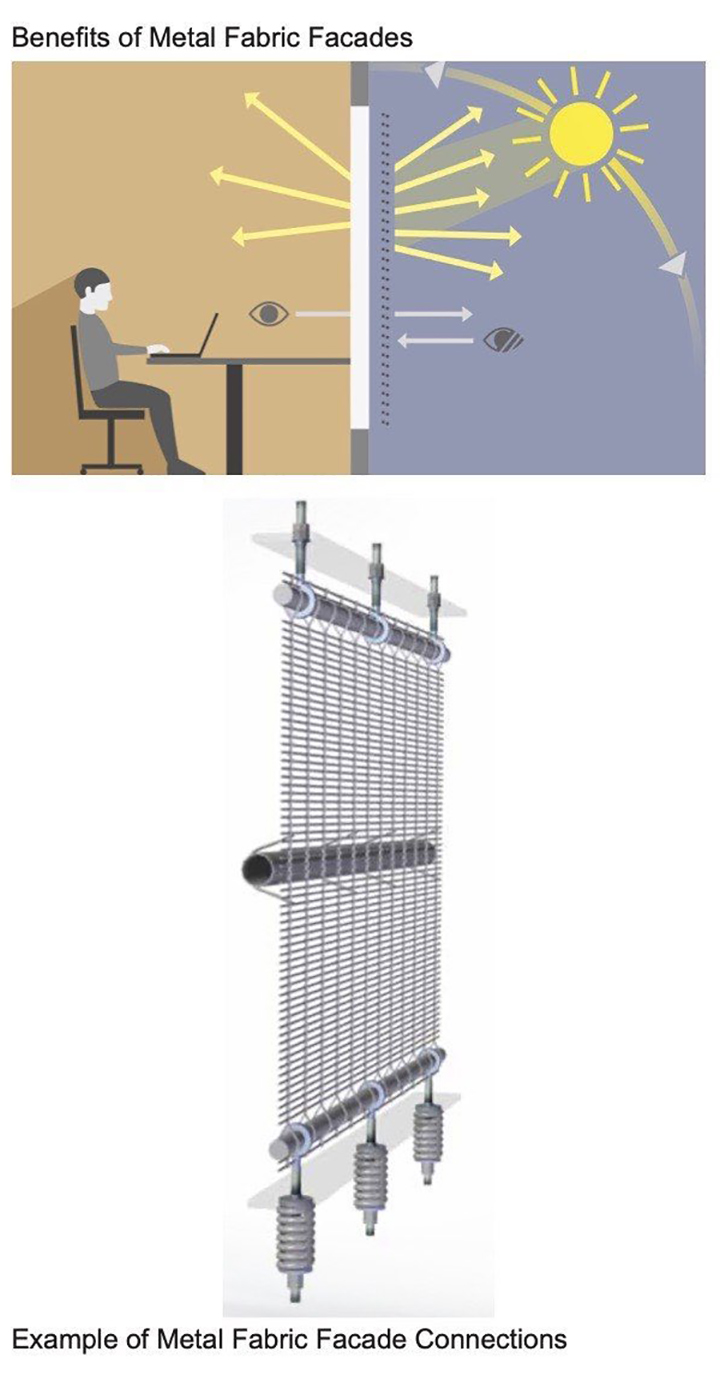

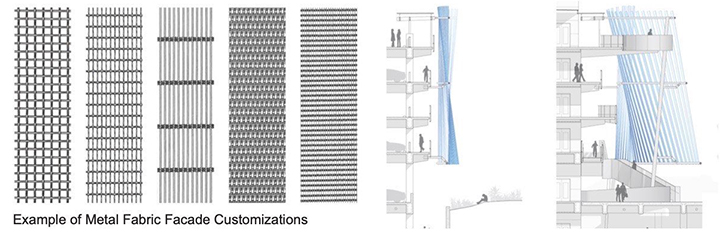

The new proposed detail offers a look at the use of a metal fabric, as opposed to the expanded aluminium mesh. Metal fabric involves small strips or wires of metal which are weaved into a kind of fabric mesh. There is a wide diversity of mesh weave types, and a very wide range of colour options, allowing for expansive design possibilities and mass-customization.

For this new detail, the fabric could be made of an aluminum metal mesh fabric, with connections of the same metal, in order to relate to the aluminum side panels beneath. The mesh is quite small, so it acts as a much better light filter than the New Art Museum’s current large expanded aluminium mesh, while still allowing in a good amount of filtered incident light. The metal fabric also gives the exterior of the building a very monolithic feel, just like the current expanded mesh, but it is very transparent when viewed straight on from inside the building’s windows. This eradicates the “dispiritingly correctional effect” of the use of expanded aluminum panels over the windows, and instead allows for a very good view straight through the glass, while still hiding the interior when looking from the exterior.

The new proposed detail offers a look at the use of a metal fabric, as opposed to the expanded aluminium mesh. Metal fabric involves small strips or wires of metal which are weaved into a kind of fabric mesh. There is a wide diversity of mesh weave types, and a very wide range of colour options, allowing for expansive design possibilities and mass-customization.

For this new detail, the fabric could be made of an aluminum metal mesh fabric, with connections of the same metal, in order to relate to the aluminum side panels beneath. The mesh is quite small, so it acts as a much better light filter than the New Art Museum’s current large expanded aluminium mesh, while still allowing in a good amount of filtered incident light. The metal fabric also gives the exterior of the building a very monolithic feel, just like the current expanded mesh, but it is very transparent when viewed straight on from inside the building’s windows. This eradicates the “dispiritingly correctional effect” of the use of expanded aluminum panels over the windows, and instead allows for a very good view straight through the glass, while still hiding the interior when looking from the exterior.

There are many benefits to using the metal fabric mesh, which, surprisingly, has not been commonly used in too many building facades, most of which are on parking garages. When it has been used, it is almost always either used like a curtain, or brought quite far away from the inner sides of the buildings, as almost a second facade or shell. For this new detail, this design is being re-fabricating as more of a skin, similar to the aluminum mesh currently on the New Art Museum, and less as a separate entity shell or curtain. Over the solid aluminum panels below, the metal fabric will create the softening of corners and play of light as more of a facade skin layer, creating the same type of clean look as the current New Art Museum. The mesh can be seen through when looked at from straight on, so the aluminum panels below this will allow the building to still remain blurred and monochrome from all directions.

The wire mesh fabric is able to be tensioned over the full height of the facade using flat tension profiles and pressure springs with tube frames and wire connections at each floor level to help with any lateral wind loads. This is a common technique for attachment of wire mesh fabric, however, this will be done in a completely continuous method, where the mesh will wrap around a metal bar at the base of the overhangs, top of the flat roofs, and all corner conditions. The tension supports and springs will then connect horizontally to the existing structure of the building. The new detail shows these connections at the base of the overhang. Instead of using metal panels which stop at the corner of the overhang, the mesh will wrap around and continue straight to the structure at the side of the overhung facade.

In order to get this detail out to others, the manufacturers of the metal fabric mesh could be contacted to use the detail as an example of a new possibility and way to fabricate this mesh for a very continuous and clean facade. The possibilities for this mesh are endless, and this is just one new detail of how it could be used, but if there is ever a building inspired by the New Art Museum that is looking to correct its mistakes, this is the detail which they could look into. The cost can also be advertised as much less than a panel cladding or a framed solution, since there is less substructure involved with the metal fabric cladding. The mesh fabric can be made of any type of metal, but the sustainability factor of using metal can also be advertised, as it is a material which is very durable, and can also be recycled and reused an indefinite amount of times without losing its qualities. The fabric mesh is also able to be integrated in sliding or hinged frames for removable solutions for shading devices which are not permanent.

![]()

![]()

Justin Arbesman

Project 2B: Topology Optimization

Project 2B: Topology Optimization

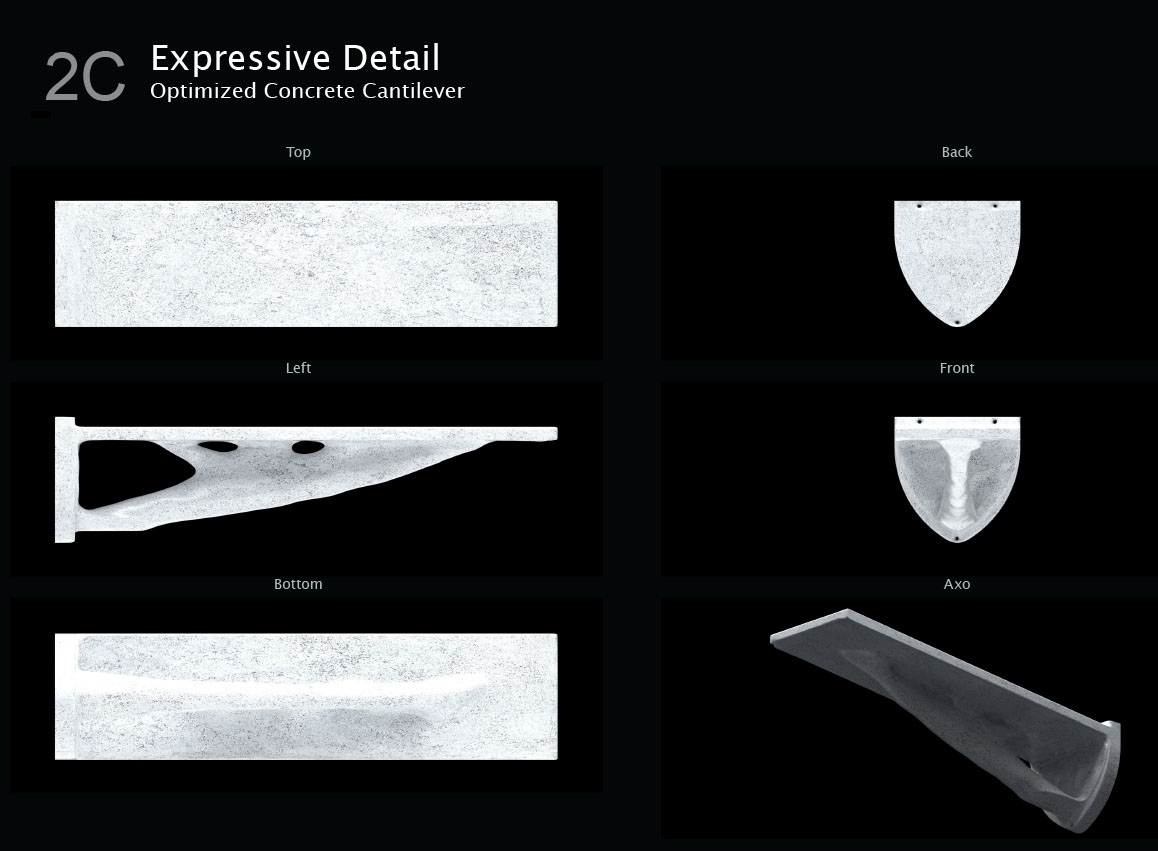

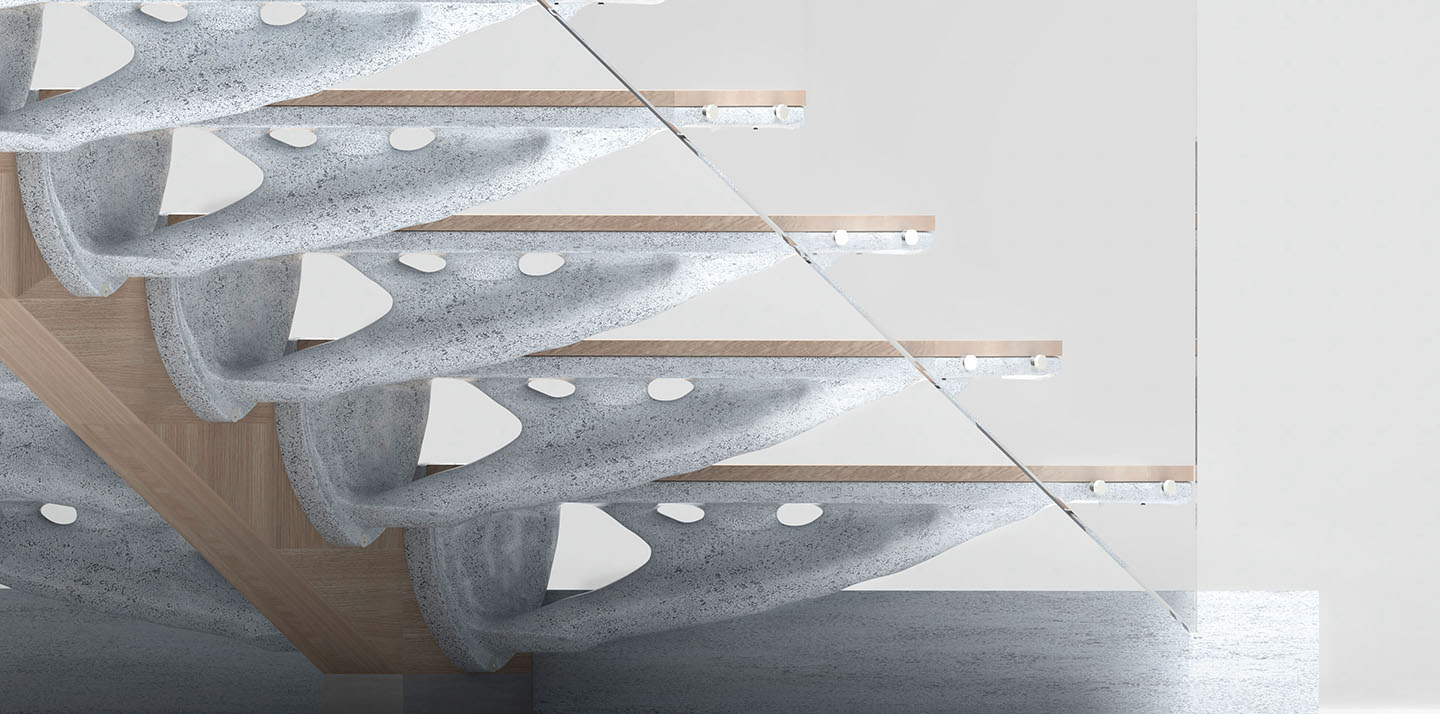

Detail Intent

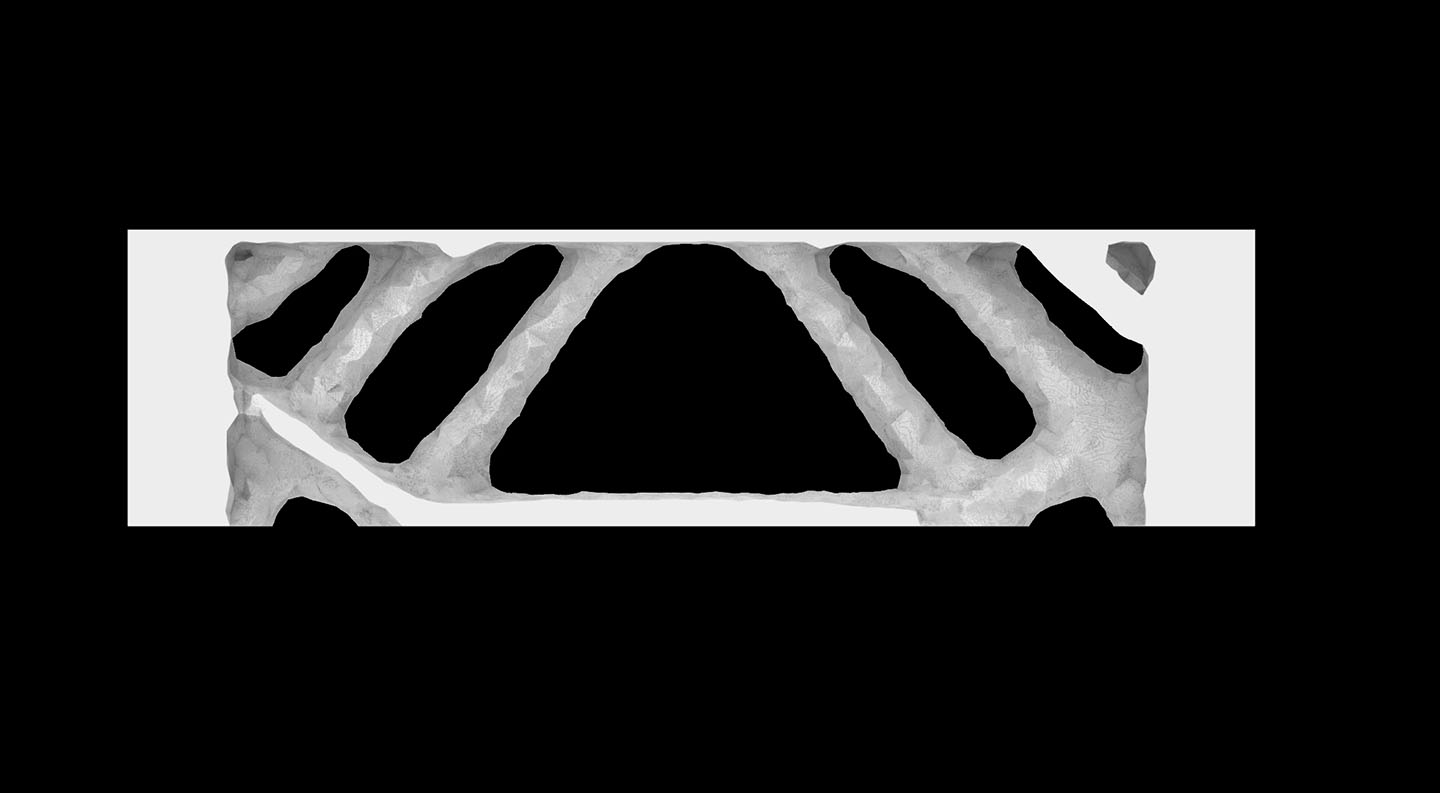

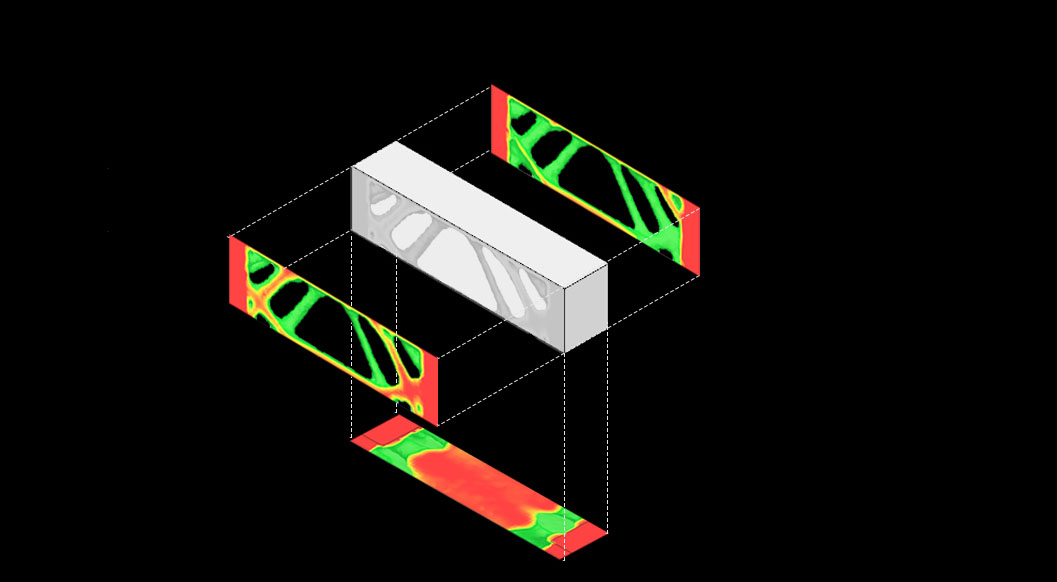

The natural world exists in resource scarcity. All forms of life have hidden optimizations within that allow for their form to exist. Bird skulls have three layers each connected with what can be called columns of microscopic bone allowing for a light yet rigid structure to not weigh the bird down. Lily Pads stem from a single root and branch out varying the thickness of their components depending on the forces acting on it. These natural optimization processes in nature beautifully tackle the organisms largest hurdles when it comes to living on this planet. We now have begun to deconstruct and reinvent these processes in the digital age. Utilizing these algorithmic processes, we can take our first principles of design and elevate them to a human designed nature. While not entirely necessary on this project by Herzog and de Meuron, the method of topology optimization is a field beginning to take over the aerospace and automotive industries and thus should be looked at in the world of architecture.

The natural world exists in resource scarcity. All forms of life have hidden optimizations within that allow for their form to exist. Bird skulls have three layers each connected with what can be called columns of microscopic bone allowing for a light yet rigid structure to not weigh the bird down. Lily Pads stem from a single root and branch out varying the thickness of their components depending on the forces acting on it. These natural optimization processes in nature beautifully tackle the organisms largest hurdles when it comes to living on this planet. We now have begun to deconstruct and reinvent these processes in the digital age. Utilizing these algorithmic processes, we can take our first principles of design and elevate them to a human designed nature. While not entirely necessary on this project by Herzog and de Meuron, the method of topology optimization is a field beginning to take over the aerospace and automotive industries and thus should be looked at in the world of architecture.

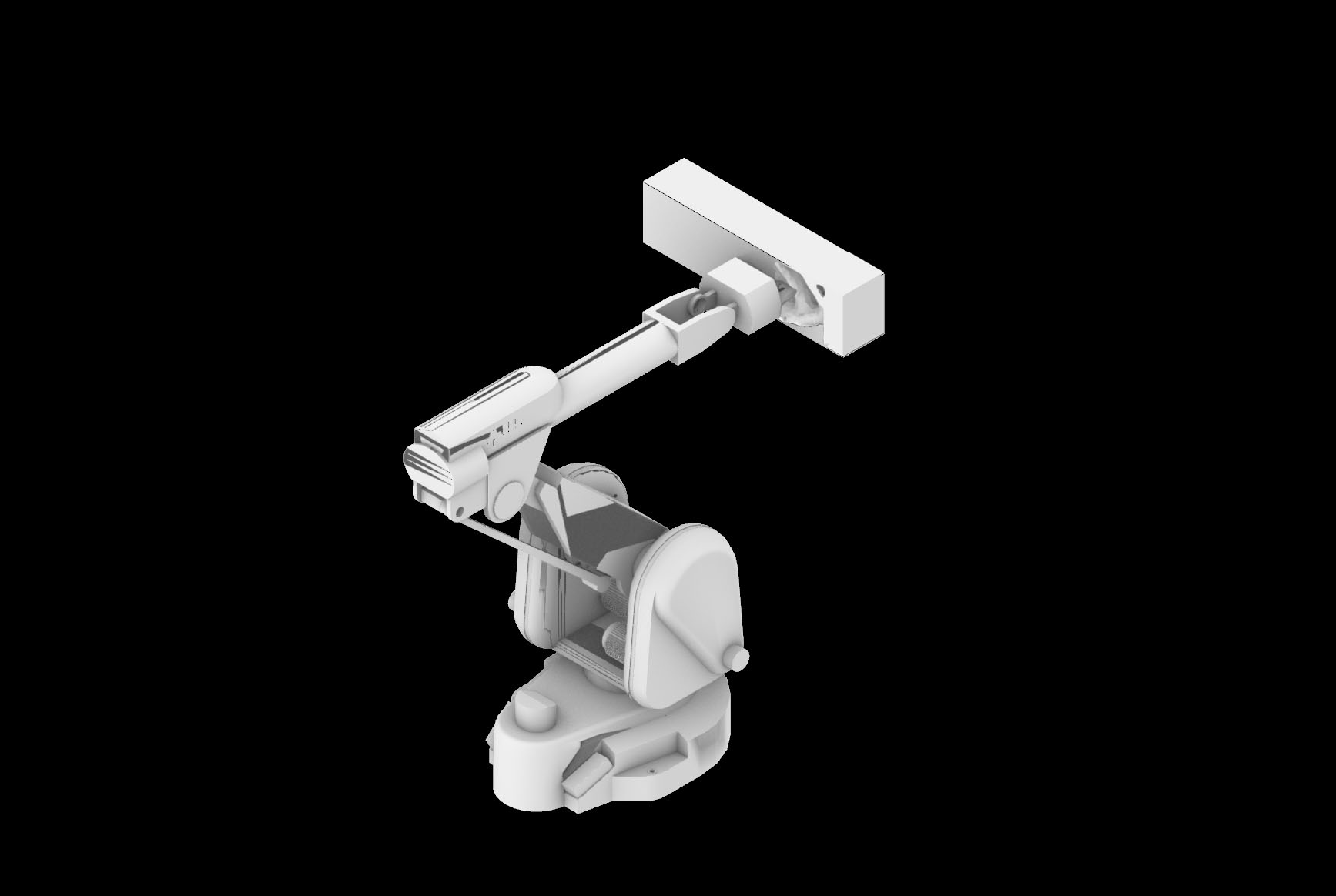

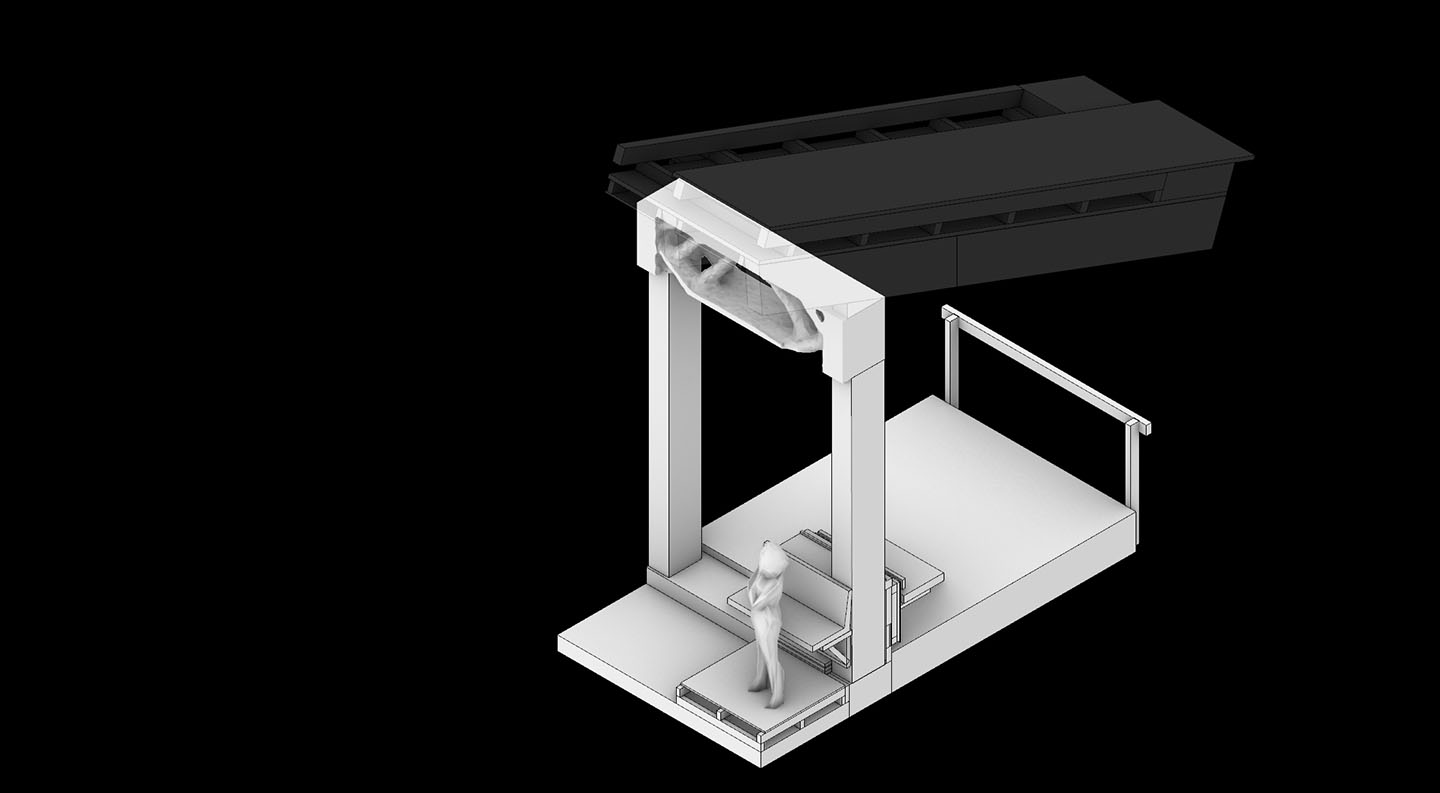

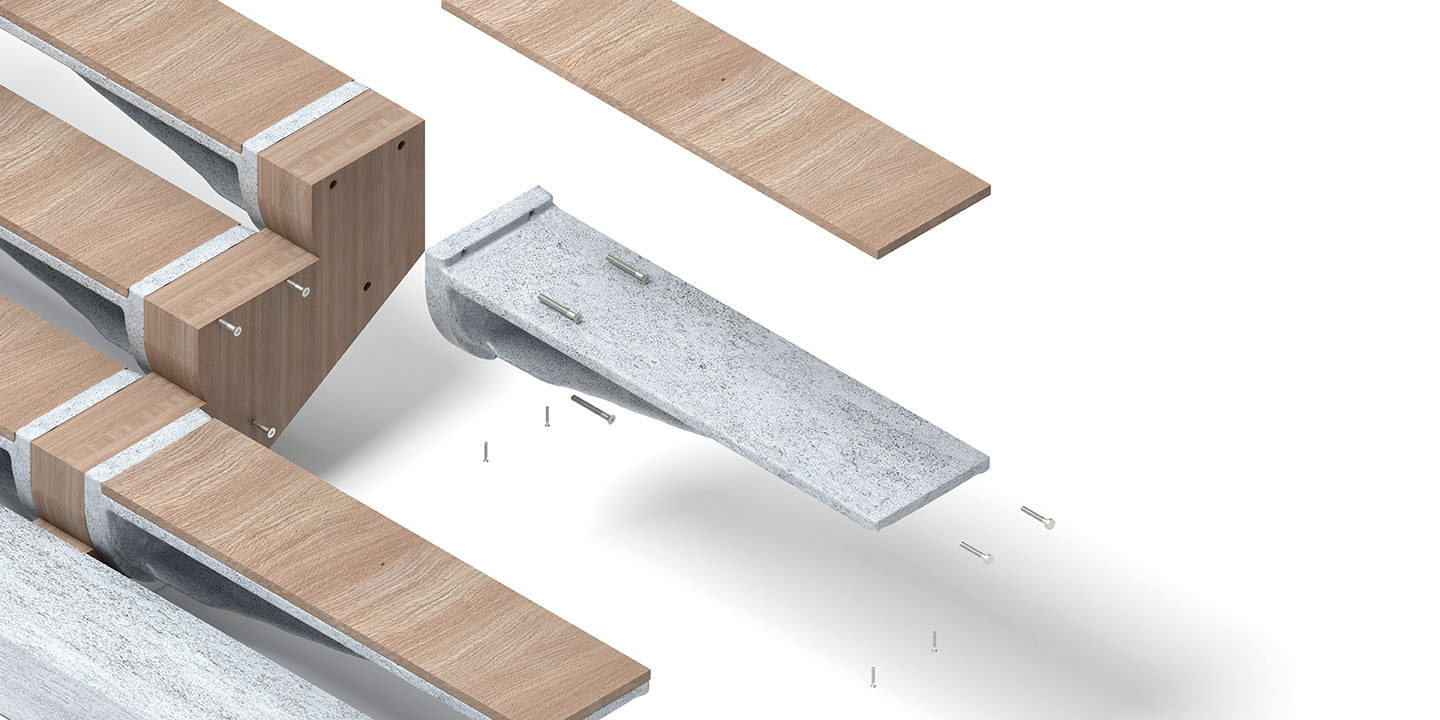

Structural engineers and architects are able to integrate the structural optimization in parallel with the standard structural calculations. Using software that is fed material properties, movement constraints, loads and load direction, the architect and engineer are able to generate force optimized forms. These forms are then further refined after the initial simulation and fed into a CAD/CAM program. With the use of a 5-axis CNC robot arm, the prefabricated components would be stripped of unnecessary material directly after the part is dimensioned. The component would then be equipped with standard heavy timber connections and used without disruption to the labor force. However, the 5-axis CNC is also capable of implementing custom complex joinery onto the part during the shaving process.

Tectonics

Then looking at a part designed using topology algorithms, even the laymen gets a feeling like nature had a role to play. The intricate, organic, and often beautiful forms that emerge give a sense of otherworldliness or of a stream of design almost unimaginable. Only through recreating processes of nature do these forms exist. Perfectly suited to its structural purposes, the optimized components visually convey the laws of nature. The results intertwine human created and naturally grown forms, a visual look into the fabric of the world. Tendrils span from one side to another, changing in size and shape showcasing the forces it counteracts. Maybe by looking at these forms more closely will we be able to further understand and conceive of structures for tomorrow.

Materiality